But it’s not only about silence – it’s about control. When a cat puts its foot to the ground, it instinctively checks the firmness beneath before it transfers its weight. It could, if it needed to, lift the foot again without losing its balance. Only the muscles needed for movement are under any tension – the rest of the animal’s body is relaxed and at ease. There is a subtle muscular control that, for a human, would be almost reminiscent of the flowing Chinese martial art of tai chi. Tassa is to move like that – silently, with liquid grace and total control.

It’s never going to be a common word – it has a specialized and very precise meaning. Tassa is not the way we move around every day. It is never going to be used to describe how we walk to the pub or carry the rubbish out to the bins. But as we creep upstairs late at night, or try not to wake the baby, or avoid disturbing the teenager at her homework, tassa is the word that should be on our mind.

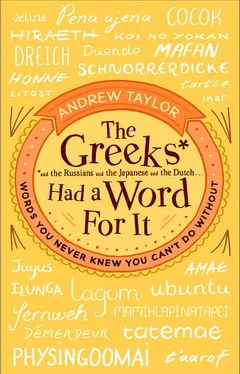

A pile of books waiting to be read

Book lovers all have the same guilty secret. And they all dread the same question when people see their collection of books.

‘So have you read them all?’

It’s a perfectly civil question and quite flattering, since it suggests that all the information, knowledge and wisdom distilled in the pages on your shelves might just be replicated in your brain, but it makes most booklovers quail. Because the honest answer, for most of us, is ‘No’.

How can you explain about the book that you bought when you were passionately interested in a particular subject, only to find when you got it home that it was as dull as last month’s newspaper? Or the ones that you snapped up on a whim in the bookshop because their covers looked so appealing? Or the ones – a growing number as you get older – that you might possibly have read years ago, if only you could now remember the tiniest hint of what they contain. Or the ones you were given as presents, which you never much liked from the moment you opened the parcel. When the excuses run out, the answer is the same.

There are books on our shelves that we haven’t read.

We will read them one day, we tell ourselves with the best of intentions, and so we keep them in convenient piles around the room or next to our bed. When we have time, we say, or we promise ourselves a few days off, or we keep a pile ready for our summer holiday and another for when we wake in the night. But somehow, inexplicably, the piles just keep growing.

This practice, as the Japanese will tell you, is tsundoku ( TSOON-do-coo ). It literally means ‘reading pile’, but it’s used to describe the act of piling up books and leaving them unread around your house. To those not infected with the book-collecting bug, the tottering and apparently random piles may seem to be nothing but an unsightly mess, but the dedicated practitioner of tsundoku will know where each book is as clearly as if they were catalogued by computer.

You could expand the word’s meaning to cover any of the pleasant actions that we mean to take one day – the visits to old friends, the things we’re going to buy, the holidays in exotic countries. They’re not something to beat ourselves up about, because piling up treats to fill the future is one of the best things about being alive. There is no shame in those piles of books that you will read – perhaps – when you have the chance.

If we had no tsundoku in our lives, it would indeed be a bleak and cheerless world.

The embarrassing sudden realization that, somehow, you’ve eaten it all …

In English, we have words and we put them together to form a sentence. There can be very short sentences – ‘I ran’, say, or ‘I slept’. But the shortness of these sentences is a result of their simplicity, not the cleverness of the words themselves. In Georgia, they do things differently. They can tell a whole story, all in a single word.

Shemomechama ( shem-o-meh-DJAHM-uh ) means ‘I didn’t mean to, but I suddenly found I had eaten all of it.’ It may not be an entirely convincing plea from a small boy standing in front of you with an empty plate and a guilty expression, but it’s an impressively complex idea to get across in a single word.

They can manage it largely because Georgian – one of a small group of languages in the Caucasus, with its own delicate and elegant script – has a number of varied and expressive prefixes, which can add subtle shades of meaning to the most simple verbs. So in this case, the mechama part of the word means ‘I had eaten’, but the shemo prefix combines an expression of desire, a reluctance to fulfil that desire and then a slightly shame-faced, shoulder-shrugging admission that temptation was too great.

Not even the Georgians can squeeze into that word a full explanation for why you’ve been so weak – maybe the food was particularly tasty, maybe you were unbearably hungry, or maybe you just kept nibbling away with your mind on other things and suddenly discovered to your horror that you’d eaten the lot. But that probably doesn’t matter – trying to come up with a reason isn’t going to make it any better as an excuse. Whoever you’re telling is still going to be pretty cross, although probably not as cross as in two other examples of the same prefix at work.

The first, shemomelakha ( shem-o-meh-LAKH-uh ), is the sort of thing you might say to the magistrate. It means, worryingly, ‘I only meant to rough him up a little, but I somehow found I had beaten him half to death.’ And the second, which could also get you into serious trouble, is shemometqvna ( shem-o-meh-TKV’N-uh ), which is not used in polite society and means something like ‘I was only thinking of a quick kiss and cuddle to begin with, but I somehow ended up … Well, the flesh is weak.’

Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland , invented the term ‘portmanteau word’ to describe the idea of two meanings packed into a single word, like the two halves of a large suitcase. To carry on the metaphor, shemo is not even a word in its own right but deserves to be thought of as a whole matched set of luggage. It is a triumph of compression.

English speakers are unlikely to get their tongues round the complexities of shemomechama – and, incidentally, if you think that Georgian is hard to pronounce, you should see the script. (The Romans, who knew a thing or two about empires and foreign cultures, wrote the language off as incomprehensible.) But with due apologies for butchering their language, we might borrow the prefix and use it on its own, to mean ‘I didn’t meant to, but somehow it just happened …’ – whatever ‘it’ might be.

‘Did you realize that you were doing 40 mph in a 30 mph zone, madam?’ And the reply is a guilty shake of the head and a muttered, ‘ Shemo .’

‘You said you were going to be home by seven, and it’s nearly three in the morning!’ How did that happen? ‘ Shemo .’

Social faux pas of forgetting the name of the person you’re introducing

No doubt someone, somewhere, thought years ago that they were doing the world a favour when they invented the name badge that people could wear at conferences or parties. Not only will it simplify introductions, they must have thought, it will also save the embarrassment of forgetting somebody’s name.

The problem is that the people most likely to forget names are those who are middle-aged or more, and they are also the most likely to be short-sighted. The embarrassment caused by having to lean forwards and peer at a woman’s chest, in particular, is far worse than an honest admission that you’ve forgotten her name. Better by far, the Scots might say, to tartle ( TAR-tll ).

Читать дальше