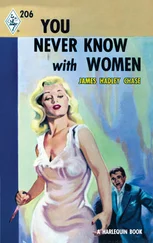

James Hadley Chase

You Never Know With Women

The rat hole they rented me for an office was on the sixth floor of a dilapidated building in the dead-end section of San Luis Beach. From sunrise to dusk the noise of the out-town traffic and the kids yelling at one another in the low-rent tenement strip across the way came through the open window in a continuous blast. As a place to concentrate in, it ranked lower than the mind of a third-rate hoofer in a tank-town vaudeville act.

That was why I did most of my head work at night, and for the past five nights I had been alone in the office flexing my brain muscles while I tried to find a way out of the jam. But I was licked and I knew it. There was no way out of this jam. Even at that it took me a couple of brain sessions to reach this conclusion before I decided to cut my losses and quit.

I arrived at the decision at ten minutes after eleven o’clock on a hot July night exactly eighteen months after I had first come to San Luis Beach. The decision, now it was made, called for a drink, and I was holding up the office bottle in the light to convince myself it was as empty as my trouser pockets when I heard footsteps on the stairs.

The other offices on my floor and on the floors below were shut for the night. They closed around six o’clock and stayed that way until nine the following morning. I and the office mice were the only inhabitants in the building, and the mice had popped into their holes as the footsteps creaked up the stairs. The only visitors I’d had in the past month were the cops. It didn’t seem likely that Lieutenant of the Police Redfern would call at this hour, but you never knew. Redfern did odd things, and he might have thought up an idea of getting rid of me. He liked me no more than he liked a rattlesnake — perhaps a little less — and if he could run me out of town even at eleven o’clock at night it would be all right with him.

The footsteps came along the passage. They were in no hurry: slow, measured steps with a lot of weight in them.

I felt in my vest pocket for a butt, struck a match and lit up. It was my last butt, and I had been saving it up for an occasion like this.

There was a light in the passage, and it reflected on the frosted panel of my door. The desk lamp made a pool of light on the blotter, but the rest of the rat-hole was dark. The panel of light facing me picked up a shadow as big feet came to rest outside my door. The shadow was immense. The shoulders overflowed the lighted panel; on the pumpkin-like head was the kind of hat the cloak-and-dagger boys used to wear when I was knee-high to a grasshopper.

Finger-nails tapped on the panel, the door-knob turned, the door swung open as I shifted the desk lamp.

The man who stood in the doorway looked as big as a two-ton truck. He was as thick as he was broad, and had a ball-round face, skin tight with hard, pink fat. A black hairline moustache sat below a nose like the beak of an octopus, and little black eyes peered at me over two ridges of fat, like sloes in sugar icing. He might have been fifty, not more. There was the usual breathlessness about him that goes with fat people. The crown of his wide black hat touched the top of the door, and he had to turn his gross body an inch or so to enter the office. An astrakhan collar set off his long, tight-fitting black coat and his feet were encased in immaculately polished shoes, the welts of which seemed a good inch and a half thick.

“Mr. Jackson?” His voice was hoarse and scratchy and thin. Not the kind of voice you’d expect to come out of the barrel of a body he carried around on legs that must have been as thick as young trees to support it.

I nodded.

“Mr. Floyd Jackson?”

I nodded again.

“Ah!” The exclamation came out on a little puff of breath. He moved further into the room, pushed the door shut without turning. “My card, Mr. Jackson.” He dropped a card on the blotter. He and I and the desk filled up the office to capacity, and the air in the room began to fight for its breath.

I looked at the card without moving. It didn’t tell me anything but his name. No address; nothing to say who he was. Just two words: Cornelius Gorman.

While I looked at the card, he pulled up the office chair to the desk. It was a good strong chair, built to last, but it flinched as he lowered his bulk on to it. Now he had sat down there seemed a little more space in the room — not much, but enough to let the air circulate again.

He folded his fat hands on the top of his stick. A diamond, a shade smaller than a door knob, flashed like a beacon from his little finger. Cornelius Gorman might be a phoney, but he had money. I could smell it, and I have a very sensitive nose when it comes to smelling money.

“I’ve been making inquiries about you, Mr. Jackson,” he said, and his small eyes searched my face. “I hear you are quite a character.”

The last time he called, Lieutenant of the Police Redfern had said more or less the same thing, only he had used a coarser expression.

I didn’t say anything, but waited, and wondered just how much he had found out about me.

“They tell me you’re smart and tricky; very, very tricky and smooth,” the fat man went on in his scratchy voice. “You have brains, they say, and you’re not over honest. You’re a reckless character, Mr. Jackson, but you have courage and nerve and you’re tough.” He looked at me from over the top of his diamond and smiled. For no reason at all the office seemed suddenly very far from the ground and the night seemed still and empty. I found myself thinking of a cobra coiled up in a bush: a fat cobra, sleek but dangerous.

“They tell me you have been in San Luis Beach for eighteen months,” he continued breathlessly. “Before that you worked for the Central Bonding Agency, New York, as one of their detectives. A detective who works for a bonding company, they tell me, has excellent opportunities for blackmail. Perhaps that was why they asked you to resign. No accusations were made, but they found you were living at a scale far beyond the salary you were paid. That made them think, Mr. Jackson. A bonding agency can’t be too careful.”

He paused and his little eyes probed inquisitively at my face, but that didn’t get him anywhere. “You resigned,” he went on after a pause, “and soon after you became an investigator with the Hotel Protection Association. Later, one of the hotel managers complained. It seems you collected dues from certain hotels without giving the company’s receipt. But it was your word against his, and the company reluctantly decided the evidence was too flimsy to prosecute, but you were asked to resign.

After that you lived on a young woman with whom you were friendly: one of the many young women, they tell me. But she soon tired of giving you money to spend on other young women, and you parted.

“Some months later you decided to set up on your own as a private investigator. You obtained a licence from the State Attorney on a forged affidavit of character, and you came to San Luis Beach because it was a wealthy town and the competition was negligible. You specialized in divorce work, and for a time you prospered. But there are also opportunities for blackmail, so I understand, even in divorce work. Someone complained to the police, and there was an investigation. But you are very tricky, Mr. Jackson, and you kept out of serious trouble. Now the police want to run you out of town. They are making things difficult for you. They have revoked your licence, and to all intents and purposes they have put you out of business: at least, that’s what they think, but you and I know better.”

I leaned forward to stub out my butt and that brought me close to the diamond. It was worth five grand, probably more. Smarter guys than Fatso Gorman have had their fingers cut off for rocks half that value. I began to get ideas about that diamond.

Читать дальше