Buddhism has proved a faith of remarkable attractiveness from India outward to the north and east, and so Pali and Sanskrit are extremely well known in these vast areas. But they have remained no more than liturgical languages. As a result, Buddhism’s linguistic effects have been far weaker than those of Christianity or Islam. After all, Latin, the language of Western Christianity, provided the foundation for the growth of a common language in the monasteries and then the universities of Europe in this same period (AD 500-1500). Islam propagated Arabic all round North Africa, Arabia, Palestine and Mesopotamia, persisting up to the present day, both in unchanged form as an international lingua franca for the educated and, with local variations, as the basis of many vernaculars. There is no comparable linguistic union of Buddhists, in their daily languages.

As for how the language was used in this part of Sanskrit’s story, there is little to say. In Hinduism, the virtue implicit in the very sound of the Vedas had long since been separated from any need to understand their meaning. Now once again for the Buddhists, with the language no longer widely understood, but still widely heard in chants and ceremonial, its substance and sound began to be given a mystic value of their own. Sanskrit became for many a language of mantra , ‘incantation’ and maṇḏala , ‘circle, sacred diagram’. In medieval Japan, repeating namu amida butsu , a version of nama Amitabha Buddha , ‘Bowing to you, O Resplendent Enlightened One’, was the infallible means of reaching the Pure Land after death. And to this day millions of Tibetans chant om maṇi padme hum , ‘Hail the jewel in the lotus’, a mystical phrase from Tantric Buddhism, its original sexual imagery now quite forgotten.

More pragmatically, the technology and systems associated with writing and analysing Sanskrit provided the basis for literacy in other languages. In this way, sacred languages, unavailable for direct communication among people, could still go on inspiring developments in the local vernaculars.

The advent of Sanskrit, known as fànwén , ‘Brahman writing’, in China, bongo , ‘Brahman talk’, in Japan, had only a small effect on the character-based system of writing in use in East Asia, since this had already been well established in China for over a millennium: rather, Chinese characters are often used (though only phonetically) to represent Sanskrit itself in the Buddhist practice of these countries.

One effect it did have was on Chinese phonetics. Chinese scholars of the Tang period (seventh to eighth centuries), knowing the Sanskrit alphabetic tradition could identify the initial consonants of characters, called them zìmŭ , ‘word mothers’, apparently after the Sanskrit term mātṛkā , ‘maternal’, which is also a letter of the alphabet. These were used to systematise the traditional practice for indicating pronunciation in dictionaries: Chinese dictionaries have always done this by what is called fànqiě , linking a character with two others, one with the same initial consonant, and the other with the same tone and rhyme. Putting this into a systematic chart was a very modest step in linguistic understanding, since no further analysis of the rhyme part (for example, into vowels and consonants) was undertaken. [406]

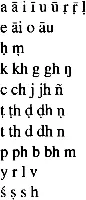

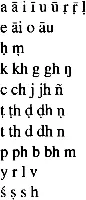

There is also an interesting curiosity in one of the other writing systems used in this vast area of Asia. [771]Japan owes the order of symbols in its syllabary, the so-called kana , or go-jū-on , ‘fifty sounds’, to the order of letters in Indian alphabets. The order of Sanskrit letters is conventionally

This is not an arbitrary order like our ABCD… [772]Rather it appeals to various purely phonetic properties of the sounds represented. So, for example, all the consonants are placed in an order where tongue contact gradually advances from the back to the front of the mouth cavity. And the nasal consonants ( m, n , etc.) always come immediately after the other consonants formed at the same place of articulation. The strange order of the vowels is partly conditioned by the fact that most instances of e and o in Sanskrit actually derive from the diphthongs ai and au , and so are well classified next to their long equivalents āi and āu.

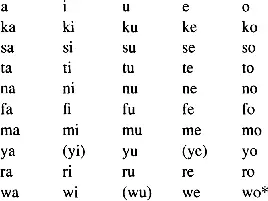

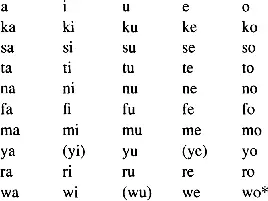

Now the Japanese kana represent syllables, rather than individual consonants. Their pronunciation has definitely changed over the last millennium, but using the most ancient pronunciation reconstructible, we can state the conventional order as:

[773]

[773]

Immediately we note that the arbitrary order of the vowels (a i u e o) is precisely as in Sanskrit, although this has no motivation in Japanese grammar. Furthermore, although there are many fewer consonants in Japanese than in Sanskrit, they occur in almost exactly the same order as in the Sanskrit alphabet. In fact, there is only one apparent exception, s, which occurs where c or ṯ should be, not at the end like the Sanskrit sibilants. In fact there is reason to believe that the pronunciation of this phoneme was actually [š] (English ‘sh’) or [t s], when the conventional order was set up, which means it would be closest to Sanskrit c (English ‘ch’, [tš]).

This thoroughgoing intellectual borrowing at the root of the writing system demonstrates that not just the sound of the Buddhist chants but also elements of the traditional analysis of the language had spread to Japan with Sanskrit.

Another example of Sanskrit intellectual influence on the technology of writing is the Tibetan script, which we first see in use in the eighth century AD, derived directly from the Siddha script. The earliest-known use of it is on a stone pillar at Žol near Lhasa, dated to 764. [407]

It is not quite clear if Tibet owes its literacy to Buddhism, or to attempts to modernise administration. The era of the first surviving inscriptions is precisely the time when Buddhism first came to Tibet, with the monk Śāntarakṣita. But there is no mention of Buddhism on the Žol pillar inscription, which is a record of a royal minister’s achievements. [408]

Whatever the motivation, it is clear that the Tibetan alphabet was inspired by an Indian model [774], and one that was used for the writing of Sanskrit or Prakrit. And Tibetan writing, once established, was very largely taken up with the translation of Buddhist classics from Sanskrit or Pali. This became such an industry that there was a Tibetan royal commission in the early ninth century to establish precise rules for equivalences (comparable to the ‘controlled language’ used in some industrial translation today). The result was a lowering of the literary skill displayed in translation, but such punctilious work was done that it is often possible to reconstruct lost Sanskrit originals simply on the basis of their Tibetan versions.

These religious foundations of Tibet’s Sanskrit culture were surmounted by a superstructure of wider-ranging classical literature in the thirteenth century, for then Muslim invaders devastated all the centres of higher learning in northern India, and many scholars fled northward into Tibet with their books. Nine Sanskrit pundits accompanied the Khatšhe pantšhen Śākyašrībhadra to Tibet in 1206, and fifty years later there was collaboration on Sanskrit drama, poetry and poetics between the Indian pundit Lakṣmīkara and the Tibetan scholar šoṇ-ston Rdo-rdže rgyal msthan . [409]

Читать дальше

[773]

[773]