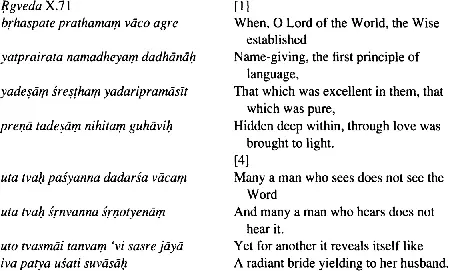

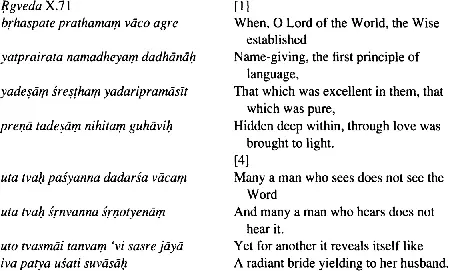

And religious uses have always loomed large in the figure that Sanskrit cuts in the world. Hindu liturgies have been intoned in the language over a continuous period of 3500 years, which is probably the age of the oldest hymns in the Rig Veda. The gods chosen to be the focus of worship have changed over the millennia, from Agni (’Fire’), Savitri (’Sun’), Varuna and Rudra in the Vedas, to Śiva, Krishna, Ganesha and Kali (and many others) today, but some gods are still with us (notably Vishnu), and the language has changed very little. In fact, in the Rig Veda there is one hymn that is an invocation of Vāc, speech itself. Here are two of its verses:

The last words show a blending of sexual and mystical imagery, often found in Sanskrit; but they also show that the skills of the linguist were early recognised. This is particularly interesting in that the discipline of grammar as it had been developed was an analysis not primarily of the religious language of the Vedas, but of a different, slightly simpler, and therefore presumably later, dialect. Pāṇini , the original fifth-century BC doyen of Sanskrit grammar, has to give extra rules to generate the forms used in the Vedas (called chandas ) from a base in ordinary Sanskrit (designated as bhāṣā —’speech’). (Panini probably lived in the academic community of Takṣaśilā , known to the Greeks as Taxila, near modern Rawalpindi in the extreme north-east of the subcontinent, now part of Pakistan.)

Furthermore, the grammar that the tradition had defined was a vast system of abstract rules, made up of a set of pithy maxims (called sūtras , literally ‘threads’) written in an artificial jargon. These sutras are like nothing so much as the rules in a computational grammar of a modern language, such as might be used in a machine translation system: without any mystical or ritual element, they apply according to abstract formal principles. [755]

Formulation in sutras became the key feature of Sanskrit academic texts, but using maxims in regular Sanskrit and not this complex meta-language. Whereas Western didactic texts until the modern era were formulated in some Greek tradition as a set of axioms and theorems (after Euclid), or more often as didactic verse (after Hesiod), the preferred approach in the Sanskrit tradition has been to encapsulate treatises as a series of memorable aphorisms, usually phrased as verse couplets. So much so that there is even a sutra to define the qualities of a good sutra:

svalpākṣaram asandigdhaṃ sāravad viśvatomukham

astobham anavadyaṃ ca sūtraṃ sūtravido viduẖ

brief, unambiguous, pithy, universal,

non-superfluous and faultless the sutra known to the sutra-sages.

This approach was very much a part of another distinctive feature of Sanskrit linguistic culture, namely a strong ambivalence about the value of writing. Reliance on language in its written form was seen as crippling, and not giving true control over linguistic content. Hence this proverb:

pustakasthā tu yā vidyā parahastagatam dhanam

Knowledge in a book—money in another’s hand. [369]

In this ancient India was like many cultures as widely divided as the Druids of Gaul in the first century BC [370]and modern Guatemala (where Mayans remark that outsiders note things down not in order to remember them, but rather so as not to have to remember them). [371]Even Socrates recalled a story that when the the god Thoth first offered the craft of writing to the king of Egypt, the king was not impressed: ‘it will set forgetfulness in the minds of learners for lack of practice in memory’. [372]The doyens of Indian learning took this undeniable side effect of book learning very much to heart.

Even though the language had undergone a full phonological analysis by the fifth century BC, which was even incorporated into the official order of letters in the alphabet, reliance on written texts for important (especially spiritually important) documents was decried. Hence another saying:

vedavikrayiṇaçcāiva vedānāṃcāiva dūṣakaẖ

vedānāṃ lekhakaścāiva tevāi nirayagāminaẖ

The sellers of the Vedas, the misreaders of the Vedas,

the writers of the Vedas, all go on the path to hell. [373]

By contrast the ideal was the rote learning of all the principal texts, through judicious use of mnemonic techniques. This learning then made possible true engagement with all aspects of them, including the composition of new texts and commentaries, which might indeed benefit from being written down.

The character of the language that received this attention has already been exhibited in the quotations. It was a typical ancient Indo-European language, with nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs all highly inflected in a system that, although susceptible to elegant analysis (as Panini and the grammatical tradition demonstrated), was rife with special exceptions. Words tended to be polysyllabic, and their length was often increased by the propensity of the language to tolerate compounds of almost unlimited length, a feature of Sanskrit that became more extreme (in all genres of literature) as the centuries and millennia wore on.

The vocabulary is vast: there are over ten thousand nominal (i.e. nonverbal) roots in the traditional thesaurus for poets ( Amarakoṣa , ‘the Immortal Treasury’, organised of course into sutras for memorisation) and, when verbs and compounds are allowed in, Monier Williams’ 1899 dictionary runs to 180,000 entries. [756]This means that there are vast resources in near-synonyms: at an extreme, John Brough claims there are fifty synonyms for ‘lotus’, a favourite concept of Sanskrit poetry in both literal and metaphorical senses. [374]Words tend to have multiple senses anyway: the most straightforward word for lotus, padma has eleven extra senses in the neuter gender ( lotus-like ornament, form of a lotus, root of a lotus, coloured marks on the face and trunk of an elephant, an army formation, a trillion ( 10), lead, a tantric chakra, a mole on the body, a spot, part of a column ) and eight more in the masculine ( temple, quarter-elephant, species of serpent, Rama, a treasure of Kubera, a mode of sexual enjoyment, a posture in meditation, a treasure connected with magic). These lexical resources are exploited to the full in Sanskrit poetry, which is gratuitously allusive and periphrastic, and addicted to śleṣa or punning.

But we have already noted that a special characteristic of Sanskrit is a complicated system of word liaison. This is known as sandhi (’putting together’). It means that word boundaries are often effaced, and a single stream of syllables, as pronounced or even written, becomes susceptible to multiple interpretations. The combined result of these two properties of Sanskrit is an opportunity for punning on an almost inconceivable scale. This opportunity was amply taken up in literary composition. The ultimate in this was achieved by the poet Kavirāja (’poet-king’), who in his Rāghavapāḏavīya (twelfth century AD), set himself the task of retelling simultaneously the stories of both the great epics of India, the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata , in ambiguous (and highly ornate) verses. In a way, this can be seen as a release of meaning from its expression in words, for it is difficult to conceive how the work could have been understood, in either of its senses, without active and detailed pre-knowledge by the audience of the tales being told. Author and audience share the stories, but are focused exclusively on the verbal details of their expression. This in practice forces not only the use of ambiguous terms, but an analogy to be set up between the narrative flow of the two epics. So, to quote one couplet (vi.8):

Читать дальше