First the Assyrian and Babylonian wars in Palestine created a large Aramaic-speaking émigré community in the Delta area. This would have been the end of Egyptian’s language monopoly in the country, not very significant in itself. But then the country was penetrated by numerous business-minded Greeks, brought in by the Saite dynasty to buttress an alliance against Near Eastern powers, and granted their own, Greek-speaking, entrepôt in Naucratis in the Delta. Egypt was now very much a multilingual society, with foreigners’ languages more and more associated with higher prestige. The Persian conquest, and a succession of foreign rulers from Persia and then (after Alexander) Greece, meant that now higher-level administration began to be conducted in a language foreign to Egypt: in Aramaic for two hundred years, and then in Greek for a millennium. [79] Aside from Cleopatra’s well-known bravura performance, Peremans ( 1964) finds little evidence of bilingualism in Ptolemaic Egypt, and much of Greeks and Egyptians ( egkhōrioi , ‘locals’) sticking to their own languages. Some famous Egyptians, such as the high priest and Greek historian of Egypt, Maněthō , did reach high rank in what remained to the end a Greek-speaking hierarchy. But so many public documents were bilingual (the most famous being the Rosetta Stone, but also judicial notices relating to private cases) that the population could not have been. He also quotes a touching letter: ‘I was glad, both for you and for myself, to learn that you were learning Egyptian writing, because now you can come to the city and teach the children of Phalu … es the enema doctor, and have a means of support for your old age’ (p. 57). Despite the mention of writing, the tutor was presumably to be employed to teach the middle-class Egyptian children Greek, not vice versa.

Linguistically, not much would have changed when the Romans unseated the Greeks in 30 BC, other than a small influx of Latin speakers, principally soldiers. But this change of government was to prove the profoundest turning point for the fate of the language: Egypt was no longer to be governed by its own kings in its own interest, but by provincial governors as a useful bread basket for Rome, and (increasingly) a destination for rich tourists.

What all the invasions had in common was the fact that they were not nomadic movements: they were military affairs conducted by well-organised armies in pursuit of commanders’ global political aims. The point in controlling Egypt was to be associated with its ancient glory, and to appropriate its present agricultural wealth. Otherwise, Egypt was to be kept true to its traditions, and so the only population movements were movements of elites, and small groups such as the Jews. Egyptian civilisation had, however, become a hollow show. There was no longer any pharaoh to hold the country through maR ‘at and perform the sacrifices, unless the Roman emperor happened to be visiting, and by the third century AD even this pretence had been abandoned.

The one elite activity retained by Egyptians was religion, and the language provided a link between its priests and the common people. Nevertheless, after three centuries of Roman rule even this link was to weaken. The local Christian community had grown, first in the face of Roman persecution, and then with official support, adopting Egyptian rather than Greek as its language. In this way, it provided a new focus, of a spiritual kind, for Egyptian loyalty. But its growing strength was characteristically marked with intolerance, particularly towards the ancient religion. How were the Christians to know that in destroying it, they were also pruning away the deepest roots that anchored and sustained their separate identity? By the fourth century AD, Egypt had become a Christian country whose populace spoke Egyptian, but whose administration and cultural life were conducted in Greek. It was still true that Egyptian’s one elite activity was religion, but now this was the local version of the Christian faith.

In 641, when political control moved to Arabic speakers, there was no space left for the elite activities in Greek. They soon withered, although some formal use of Greek continued for over a century. Religion was to yield much more slowly. But this was not just another political conquest: Islam, unlike Alexander and Augustus Caesar, aspired to win over all. When it did, the last motive for retaining Egyptian was removed: converts moved into a new confessional community, Arabic-speaking and cosmopolitan. Egyptian was left as the language of liturgy for those who were determined to hang on to their Christian faith, a gradually shrinking minority.

Even in hindsight, it is difficult to say whether Christianity was more of a blessing or a bane to Egyptian. It provided a strong ritual focus for the Egyptian-speaking community under Roman secular rule; but it was militant in cutting the links the language had had with its national pagan past. It provided a new synthetic identity, that of ‘Egyptian Christian’ or Copt, to replace the ancient one, an identity that was to last for many centuries, and for a small minority even until the present day. But the theological motivation for a separate Egyptian sect of Christianity, promoted as a universal faith, was nil. Egyptian was correspondingly weaker when it faced the challenging embrace of the Arabic-speaking community: what ground was there to maintain their Egyptian identity when the gods and rituals of the land of Egypt had all been long forgotten?

Ultimately, Egyptian could not sustain itself when it ceased to be a majority language in its one and only environment, the land of Egypt. The language, like the pharaonic religion, had been a symbol of Egyptian identity. Egyptian could survive a government speaking a foreign language, as long as its religion was based in Egypt. It could not survive a foreign government and a truly cosmopolitan religion, for its speakers had nothing national left as a focus for their identity. They might as well become Arab Muslims, just like all the rest.

Coping with invasions: Chinese unsettled

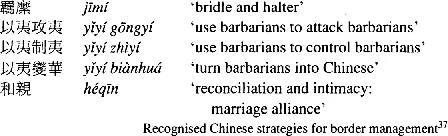

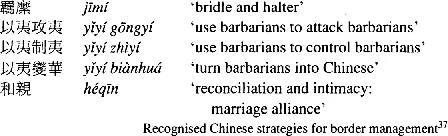

Recognised Chinese strategies for border management [362] Wilkinson (2000: 723).

The final decline of Egyptian can be understood as the long-term effect of losing the sense of its own centre.

After the Roman conquest, Egypt was at best a curiosity on the edge of Rome’s Mediterranean world, no longer responsible for its own destiny, but looking hopefully to the west. Four centuries later, the change of focus from Rome to Byzantium had had little impact; Egypt’s identity was sustained by its contributions to the new and growing faith of Christianity. Three centuries later still, the further shock of being incorporated into a quite different alien empire, one that was centred now to its east (in Damascus, then Baghdad), was more than its separate identity could stand. For the first and last time, Egyptian went into decline.

China has always viewed itself as being at the centre of its world, traditionally Tiān Xià , ‘Heaven Below’, encompassed on every side by lesser peoples, inferior in cultivation and morals. The modern word for the country, Zhōnggŭo , ’Central Realm’, seems to say it all. But another way of referring to the whole country is Sìnši zhīněi , ‘Within the Four Seas’, going back at least to Confucius. The Chinese conventionally saw themselves as living in Nine Continents within Four Seas. Each of those seas was seen as the haunt of a barbarian people, the so-called Sìyí , ‘The Four Yi’: Dōng Yí Běi Dí Xī Róng Nán Mán , ‘east the Yi, north the Di, west the Rong, south the Man’. This idea of the steppes that surround China’s heartland as seas, bizarre to anyone who looks at a modern map, had a certain reality when those steppes were populated by pastoral nomads, roaming the grassy plains to prey on the sedentary farmers who lived round the oases, the islands in this ocean. And beyond the Sìyí in the traditional world-view lay the Bāhuāng , ‘the Eight Wastes’, so it is understandable that the traditional Chinese was little tempted to explore farther abroad. [80] The Chinese have been unlike most other dominant language communities reviewed in this book in one way: they have not lumped all those speaking other languages under one unflattering name. The single term ‘barbarian’ is inescapable in English translation, but Chinese has many words, in principle all with different designations. Already in the third-century BC dictionary Erya (’Examples of Refined Usage’), the term sìhši is defined: jiŭyí bādí qīróng liŭmán , ‘the 9 Yi, the 8 Di, the 7 Rong and the 6 Man’ ( Erya , s.v. Sidí , cited in Wilkinson 2000: 710). Yet another term was Fān , from the Chinese point of view divided into the , shēngfān , and , shúfān, ‘raw’ or ‘cooked’, depending on whether they had begun to settle to civilised Chinese ways. Not that this multiplicity betokened any particular discernment or respect for the lesser breeds. Although the different words were part of the language, they were often lumped together, e.g. Róngdí , Yídí , or used undiscriminatingly. In fact, the monosyllabic blanket terms are supplemented with more specific terms for particular tribes. These were often written out, as a kind of Chinese private joke, with insulting characters, e.g. nú , ‘slave’, in Xiōngnú , and wō , ‘dwarf’, in Wōgŭo , ‘dwarf-realm’, i.e. Japan. With urbane malice, this chanced to be pronounced in Japanese identically with wa , ‘harmony’, the term the Japanese preferred when referring to themselves.

Читать дальше