And all its members as ressortissants (i.e. when they come to France) are French citizens. It is noticeable that language is not included as an aspect in which the Union is free from distinction: that is because in the Union, everyone’s language is expected to be French.

In conformity with its explicit respect for clarity and reason, the French-language community seeks to order itself, and have an overall conception of itself, apparently far more than any other. So it is characteritic that it has given itself an international political, technical and cultural organisation, known as la francophonie. It is a matter of some satisfaction to the French government that the initiative for this came not from France but from a number of distinguished second-language speakers. Still, there may perhaps have been a certain political motivation: the founders were President Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia, Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, President Léopold Senghor of Senegal, Charles Hélou of Lebanon, and Hamani Diori of Niger. Nevertheless, France does provide up to two-thirds of the organisation’s budget. It was founded on 20 March 1970 at Niamey in Niger, central Africa, and has held summit meetings regularly, with cabinet ministers in attendance, the ninth at Beirut in 2002. Membership is not restricted to former colonies of France; indeed, Egypt recently provided the secretary-general, Boutros Boutros Ghali: characteristically it chooses to emphasise some conceptual or moral, rather than historic, relatedness.

Its current emphasis, rather surprisingly, is on protecting and enabling cultural diversity, certainly a novelty as a francophone preoccupation, and not without a whiff of l’ esprit malin , Gallic mischief, directed at the perennial rivals, les anglo-saxons. But it is well within the tradition of incisive, and sometimes disinterested, consideration of the rights of man. Political interests will out, however, and it has been difficult for the French state, in recent years, even to protect and foster such linguistic diversity as remains within its own domains. The action of the minister of education in 2002, for example, aimed at incorporating Breton-language schools into the state system, and so funding them nationally, fell foul of an article inserted into the French constitution as late as 1992—that the language of the French Republic is French. [153]

The Third Rome, and all the Russias

[154]

[154]

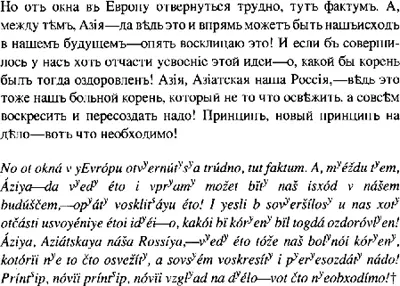

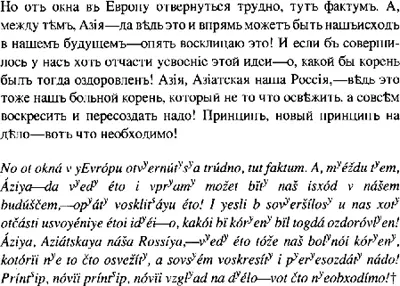

But to turn away from the window on Europe is hard, that is a fact. But, that being said, Asia—this could really be our exodus in our future—again I exclaim it! And if we could accomplish the mastery of that idea, even in part, oh, what a root would then be revitalized! Asia, our Asiatic Russia,—this too is our sick root, which we need not just to refresh, but utterly to resurrect and reconstruct! A principle, a new principle, a new view on the affair, here is what is necessary!

Fyodor M. Dostoyevsky, Gök-Tepe: What Is Asia to Us?, 1881 [621]

Russian, the last of the great European languages spread by an empire, is in many ways unlike the others.

Its domain was extended not by seaborne expeditions but overwhelmingly by military campaigns overland; hence it has come to occupy areas in a vast contiguous swath to the south and east from its homeland in the north European plain. Its bounds were expanded for the most part not by traders or missionaries, but by semi-nomadic Cossacks, explorers and military men: not out of enterprise, or a duty to win souls for Christ, but for reasons of rapine, and to buttress the global interests of its state. Russia began its conscious existence with no natural defences against the Turkic-speaking Tatars to its south, and it remained without natural defences against its Slavic-speaking cousins in Poland to the west. It was on the periphery of the cultural area with which it identified, Christian Europe; but it occupied a plain that was easily accessible to horse invaders, and also crossed by a network of navigable rivers. Ice denied it access to the open sea for most of the year. Its only natural defences lay in the severity of its winters, the sheer stickiness of its land in spring and autumn, and the vast distances that its enemies would need to cross in order to penetrate it. Conditions favoured the growth and consolidation of a single large power, with defence in depth: that power we call Russia.

Nevertheless, there were points of similarity with the other successful empire-builders of Europe. There had been a commercial motive for the expansion eastward into Siberia, the drive of outdoorsmen to trap animals for their fur, just as the French, and later the British, were to do in the northern wilderness of Canada. The Russian Orthodox Church was for most of the last millennium a potent symbol of Russian identity, [155]which accompanied the advance of Russia’s forces across south-eastern Europe and north and central Asia to the Pacific Ocean. Since its language was pointedly an antiquated form of Russia’s own, this resembles above all the imperial practice of the Church of England. And just like the British and the French in the nineteenth century, the Russian government consciously planned the later, stages of its global expansion. Central Asia, specifically the ‘Silk Road’ area of Turkestan south of the Aral Sea, was invaded in 1871-81 to protect the southern border, and as a prime source of cotton. Above all, the long-term spread of the Russian language within these vastly expanded borders was guaranteed by a flow of Russian-speaking immigrants out of the north-east into the newly Russian territories: after the 1861 abolition of the serfdom that had tied them to the land, half a million sought better fortunes eastward into Siberia in the rest of the nineteenth century. [156]

The eastern Slavs who founded Russia were among the descendants of the Veneti who, as we have seen (see Chapter 7, ‘Einfall: Germanic and Slavic advances’, p. 304), populated the shores of the Baltic in the early first millennium AD; a large number of them had not travelled southward to populate the Balkans and invade Greece (see Chapter 6, ‘Intimations of decline’, p. 257), but had rather settled towards the east, in uneasy rivalry with Baltic tribes to their north-west, and the Uralian tribes, among them the Finns, to the northeast. Indeed, the claim is made that the majority of the original population of Rus were of Finnish descent and hence language. The Slavs would have settled among them in the first centuries of the second millennium.

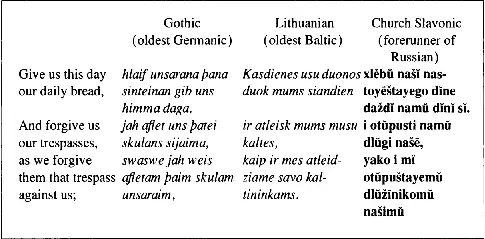

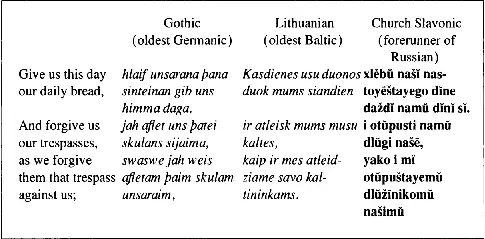

These people spoke a language that was related to that of their German neighbours to the west, and that of their Baltic neighbours (Latvians, Lithuanians and Prussians) to the north, but noticeably softer in its tone, in that consonants were palatalised and often affricated before e and i: [157]as a result, the sounds š, c and ž are highly prevalent; compare the middle of the Lord’s Prayer in the oldest forms of their languages:

[ note [158]on next page ]

The eastern Slavs, whose language would go on to form modern Russian, Ukrainian and Belorussian, almost close enough in form to be considered dialects, had been farmers rather than nomads, although the quest for furs was always a priority on their eastern frontier. By the end of the first millennium they were established in a vast forested area which ran from the Baltic coast near Novgorod due south to Kiev, and out to the east as far as Kazan. Although the people spoke Russian, their aristocracy was made up of Vikings (known as varyági or Varangians), seafarers who had invaded along the waterways from the Baltic, and who at first would have been Norse-speaking, but like so many Germanic conquerors had given up their own language. They organised the Russians on the basis of capitals ever farther south, in Novgorod, Smolensk and, in 882, in Kiev. The Dvina and Volkhov were linked by portages with the Dnieper, and so communications were established with the Black Sea, and thence the Byzantine empire. In 988 this link resulted in the conversion of Vladímir (’conquer the world’) and his Kievan court to Orthodox Christianity. In the following four centuries, the religion spread to cover the full range of eastern Slavs.

Читать дальше

[154]

[154]