In 1886, thirteen years after Cooktown was founded, Bavarian missionaries established a Lutheran mission at Cape Bedford, to the north of the town, to try to salvage the wrecked souls of the lost pagans. Later, the mission moved to a place christened Hopevale, farther inland. The mission became a sanctuary for the remaining Aborigines from the entire region and beyond. Although people speaking many different aboriginal languages were brought to Hopevale, Guugu Yimithirr was dominant and became the language of the whole community. A Mr. Schwarz, the head of the mission, translated the Bible into Guugu Yimithirr, and although his command of the language was moderate, his faulty Guugu Yimithirr eventually became enshrined as a kind of “church language,” which people can’t easily understand but which enjoys an aura much like that of the English of the King James Bible.

In the following decades, the mission underwent further trials and tribulations. During World War II, the whole community was forcefully relocated to the south, and the septuagenarian missionary Schwarz, who had arrived in Cooktown aged nineteen and had lived among the Guugu Yimithirr for half a century, was interred as an enemy alien. And yet, defying the odds, the Guugu Yimithirr language somehow refused to give up the ghost. Well into the 1980s, there were still some older men around who spoke an authentic version of the language.

Haviland discovered that Guugu Yimithirr, as spoken by the older generation, does not have words for “left” or “right” as directions at all. Even more strangely, it does not even use terms such as “in front of” or “behind” to describe the position of objects. Whenever we would use the egocentric system, the Guugu Yimithirr use the four cardinal directions: gungga (North), jiba (South), guwa (West), and naga (East). (In practice, their directions are slightly skewed from the compass North, by about 17 degrees, but this is of not much consequence to our present concerns.)

If Guugu Yimithirr speakers want someone to move over in a car to make room, they will say naga-naga manaayi , which means “move a bit to the east.” If they want to tell you to move a bit back from the table, they will say guwa-gu manaayi , “move a bit to the west.” It is even unusual to say only “move a bit that way” in Guugu Yimithirr. Rather, one has to add the correct direction “move a bit that way to the south.” Instead of saying that John is “in front of the tree,” they would say, “John is just north of the tree.” If they want to tell you to take the next left turn, they would say, “go south here.” To tell you where exactly they left something in your house, they would say, “I left it on the southern edge of the western table.” To tell you to turn off the camping stove, they would say, “turn the knob east.”

In the 1980s, another linguist, Stephen Levinson, also came to Hopevale, and he describes some of his outlandish experiences with Guugu Yimithirr direction giving. One day, while he was trying to film the poet Tulo telling a traditional myth, Tulo suddenly told him to stop and “look out for that big ant just north of your foot.” In another instance, a Guugu Yimithirr speaker called Roger explained where frozen fish could be found in a shop some thirty miles away. You will find them “far end this side,” Roger said, gesturing to his right with two flicks of the hand. Levinson assumed that the movement indicated that when one entered the shop the frozen fish were to be found on the right-hand side. But no, it turned out that the fish were actually on the left when you entered the shop. So why the gesture to the right? Roger was not gesturing to the right at all. He was pointing to the northeast, and expected his hearer to understand that when he went into the shop he should look for the fish in the northeast corner.

It gets curiouser. When older speakers of Guugu Yimithirr were shown a short silent film on a television screen and then asked to describe the movements of the protagonists, their responses depended on the orientation of the television when they were watching. If the television was facing north and a man on the screen appeared to be approaching, the older men would say that the man was “coming northward.” One younger man then remarked that you always know which way the TV was facing when the old people tell the story.

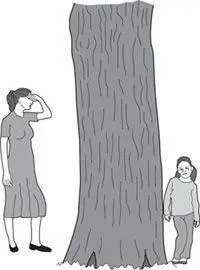

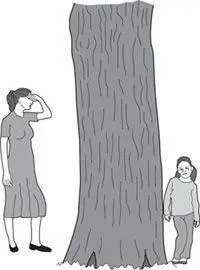

The same reliance on geographic directions is maintained even when speakers of Guugu Yimithirr are asked to describe a picture inside a book. Suppose the book is facing top side north. If a man is shown standing to the left of a woman, speakers of Guugu Yimithirr would say, “the man is to the west of the woman.” But if you rotate the book top side east, they will say, about exactly the same picture, “the man is to the north of the woman.” Here, for instance, is how one Guugu Yimithirr speaker described the above picture (guess which way he was facing): bula gabiir gabiir , “two girls,” nyulu nubuun yindu buthiil naga , “the one has nose to the east,” nyulu yindu buthiil jibaarr , “the other nose to the south,” yugu gaarbaarr yuulili , “a tree stands in between,” buthiil jibaarr nyulu baajiiljil , “she’s crying nose to the south.”

If you are reading a book facing north, and a Guugu Yimithirr speaker wants to tell you to skip ahead, he will say, “go further east,” because the pages are flipped from east to west. If you are looking at it facing south, the Guugu Yimithirr will of course say, “go further west.” They even dream in cardinal directions. One person explained how he entered heaven in a dream, going northward, while the Lord was coming toward him southward.

There are words for “left hand” and “right hand” in Guugu Yimithirr. But they are used only to refer to the inherent properties of each hand (for instance, to say “I can lift this with my right hand but not with my left hand”). Whenever the position of a hand in any particular moment is to be indicated, an expression such as “hand on the western side” is used.

In our language, the coordinates rotate with us whenever and wherever we turn. For the Guugu Yimithirr, the axes always remain constant. One way of visualizing this difference is to think of the two options on the displays of satellite navigation systems. Many of these gadgets let you choose between a “north up” and a “driving direction up” display. In the “driving direction up” mode, you always see yourself moving directly upwards on the screen, but the streets around you keep rotating as you turn. In the “north up” mode, the streets always stay in the same position, but you see the arrow representing you turning in different directions, so that if you are driving south, the arrow will be moving downwards. Our linguistic world is primarily in the “driving direction up” mode, but in Guugu Yimithirr one speaks exclusively in the “north up” mode.

A CRUMB ON YOUR SEAWARD CHEEK

The first reaction to these reports would be to dismiss them as an elaborate practical joke played by bored Aborigines on a few gullible linguists, not unlike the tall stories of sexual liberation that were told to the anthropologist Margaret Mead by adolescent Samoan girls in the 1920s. The Guugu Yimithirr may not have heard of Kant, but they somehow must have got their hands on My Adventures on the Remote Island of Zift and decided to invent something that would out-nonsense even the Ziftish concepts “bose” and “rird.” But how on earth did they manage to conjure up something so utterly unlikely and at odds with the rest of the world?

Читать дальше