At the time, it was impossible to confirm or to disprove such claims empirically, for while it is easy to test whether someone can spot the difference between two colors or not, it is far more difficult to devise experiments that can tell exactly how vividly this distinction appears to different people. Certainly it was impossible to decide the question on the basis of the available evidence, which was mostly gathered from questionnaires. As no decisive new evidence was forthcoming, the heated discussion gradually subsided over the following years and the question of the color sense remained in limbo for almost two decades, until the first attempt to conduct sophisticated experiments on the mental traits of natives in situ. Substantial progress had to wait for the 1898 Cambridge anthropological expedition to the Torres Straits, and for a remarkable man who finally swung established consensus in favor of culture-much against his better judgment.

RIVERS IN THE STRAITS

To most people who have heard of him, W. H. R. Rivers is the compassionate psychiatrist who treated Siegfried Sassoon during World War I. Rivers worked at Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh, where he was a pioneer in applying psychoanalytic techniques to help officers suffering from shell shock. Sassoon was sent to him in 1917 after being declared insane for publicly questioning the sanity of the war, throwing his Military Cross into the river Mersey, and refusing to return to his regiment. Rivers treated him with sympathy and understanding, and eventually Sassoon voluntarily returned to France. The affection, even devotion, that Rivers inspired in many of his patients seems to have lost none of its intensity years after the war. Sassoon, a man so fearless in battle that he was nicknamed Mad Jack, collapsed with grief at Rivers’s funeral in 1922. And some forty years later, in July 1963, a frail old man called in at the library of St John’s, Rivers’s old Cambridge College, and asked to see his portrait, explaining that he had been treated by Rivers at Craiglockhart Hospital in 1917. According to the librarian’s account, the man stood before the picture at the salute and thanked Rivers for all he had done for him. The visitor returned on at least two other occasions, and every time he asked to see the portrait. On his last visit he was obviously in poor health and finished with the words “goodbye my friend-I don’t suppose we shall ever meet again.”

But Rivers’s vocation as the salve of shell-shocked souls came only later in life, after a distinguished career in two other fields: experimental psychology and then anthropology. It was the experimental psychologist Rivers who was invited in 1898 to join the Cambridge University anthropological expedition to the islands of the Torres Straits, between Australia and New Guinea. But while on the islands, he developed his interest in human institutions, and it was there that he began his seminal studies on kinship relations and social organization, which are widely regarded as laying the foundations for the discipline of social anthropology and are what led Claude Lévi-Strauss to dub him the “Galileo of anthropology.”

The aim of the Cambridge Torres Straits expedition was to shed light on the mental characteristics of primitive peoples. The fledgling discipline of anthropology was struggling to define its subject matter, “culture,” and to determine the boundaries between acquired and innate aspects of human behavior. In order to shed light on this question, it was essential to determine to what extent the cognitive traits of primitive people differed from those of civilized people, and the role of the expedition was to advance beyond the mostly anecdotal evidence that had been available before. As the leader of the expedition explained, “For the first time trained experimental psychologists investigated by means of adequate laboratory equipment a people in a low stage of culture under their ordinary conditions of life.” The multivolume meticulous reports that were published by Rivers and the other members in subsequent years helped to make the distinction between natural and cultural traits clearer, and the Torres Straits expedition is thus widely credited as the event that turned anthropology into a serious science.

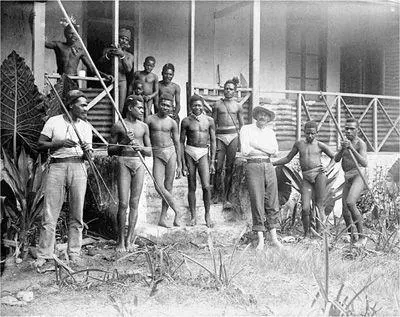

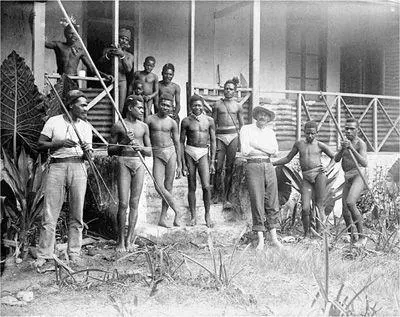

W. H. R. Rivers with friends

Rivers’s own reason for joining the expedition in 1898 was the opportunity to conduct detailed experiments on the eyesight of the natives. During the 1890s, he had been immersed in the study of vision, and so was keen to resolve the controversy over the color sense, which had not progressed much in the previous two decades. He wanted to see for himself how the color vision of the natives related to their color vocabulary and whether the capacity for appreciating differences correlated with the power of expressing those differences in language.

Rivers spent four months on the remote Murray Island, at the eastern edge of the Torres Straits, right at the northern tip of the Great Barrier Reef. With a population of about 450, the island offered a manageably small community of friendly natives who were “sufficiently civilized” to enable him to make all his observations and yet, as he put it, “were sufficiently near their primitive condition to be thoroughly interesting. There is no doubt that thirty years ago they were in a completely savage stage, absolutely untouched by civilization.”

What Rivers found in the color vocabulary of the islanders fitted well with the reports from the previous twenty years. Descriptions of color were generally vague and indefinite, and sometimes a cause of much uncertainty. The most definite names were for black, white, and red. The word for “black,” golegole , derived from gole , “cuttlefish” (Rivers suggested that this referred to the dark ink secreted by the animal), “white” was kakekakek (with no obvious etymology), and the word for “red,” mamamamam , was clearly derived from mam , “blood.” Most people used mamamamam also for pink and brown. Other colors had progressively less definite and conventional names. Yellow and orange were called by many people bambam (from bam , “turmeric”), but by others siusiu (from siu , “yellow ocher”). Green was called soskepusoskep by many (from soskep , “bile,” “gallbladder”), but others used “leaf color” or “pus color.” The vocabulary for blue and violet shades was even vaguer. Some younger speakers used the word bulu-bulu , obviously a recent borrowing from English “blue.” But Rivers reports that “the old men agreed that their own proper word for blue was golegole (black).” Violet was also mostly called golegole .

Rivers noted that often “lively discussions were started among the natives as to the correct name of a colour.” When asked to indicate the names of certain colors, many islanders said they would need to consult wiser men. And when pressed to give an answer nevertheless, they simply tended to think of a name of particular objects. For example, when shown a yellowish green shade, one man called it “sea green” and pointed to the position of one particular large reef in view.

The vocabulary of the Murray Islanders was clearly “defective,” but what about their eyesight? Rivers examined more than two hundred of them for their ability to distinguish colors, subjecting them to rigorous tests. He used an improved and extended version of the Holmgren wool test and devised a series of experiments of his own to detect any sign of inability to perceive differences. But he did not find a single case of color blindness. Not only were the islanders able to distinguish between all primary colors, but they could also tell apart different shades of blue and of any other color. Rivers’s meticulous experiments thus demonstrated beyond any possible doubt that people can see the differences between all imaginable shades of colors and yet have no standard names in their language even for basic colors such as green or blue.

Читать дальше