ramimelh: to refrain from asking, with evil intent; especially when it is clear that someone badly wants the other to ask

thehena: joy despite negative circumstances

bala: anger with reason, with someone to blame, which is futile

bina: anger with no reason, with no one to blame, which is not futile

áayáa: mysterious love, not yet known to be welcome or unwelcome

áazh: love for one sexually desired at one time, but not now

ab: love for one liked but not respected

am: love for one related by blood

The lexicon is shot through with fine distinctions in emotion, attitude, reason, and intention, presumably because these are aspects of experience that are important to women. The fact that English vocabulary doesn’t make such distinctions does not mean they are impossible to talk about in English, but, as Elgin stresses, it does mean they are more “cumbersome and inconvenient” to talk about, so that women are often accused of “going on and on” when they try to express their perspective on things.

The idea of female perspective is also carried by aspects of linguistic structure outside the word. Elgin, noting that women are often “vulnerable to hostile language followed by the ancient ‘But all I said was …’ excuse,” built into the syntax a requirement that speakers make clear what they intend when they speak. Every sentence begins with a word indicating the speech act being performed (statement, question, command, request, promise, warning) modified by an ending that marks whether that act is performed neutrally, in anger, in pain, in love, in celebration, in fear, in jest, in narrative, or in teaching. In Láadan the “It wasn’t what you said, it was how you said it” objection can’t be so easily dismissed. If a person uses the marker for a neutral speech act and then tries to claim, “Hey, I was just kidding!” the responsibility is on the speaker for not being clear, and not on the hearer for taking it the wrong way.

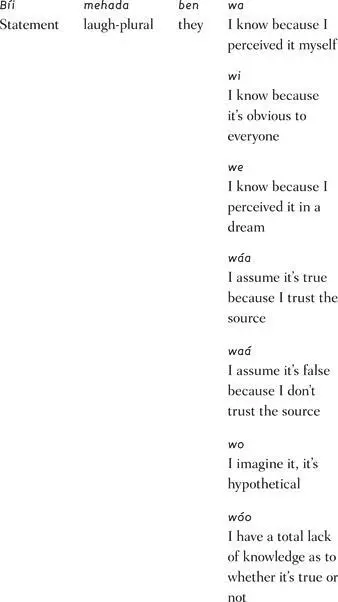

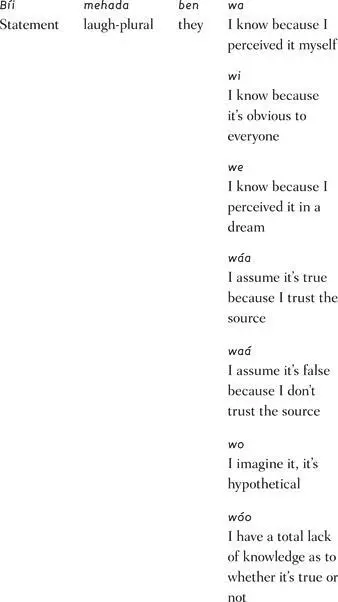

Láadan speakers also have to take responsibility for the validity of what they say. Every sentence ends with an “evidence morpheme” in which the speakers make clear on what grounds they base their statements:

“They laugh”

I’m not exactly sure what aspect of women’s perspective the evidence morphemes are supposed to make accessible (Elgin mentions that it makes exchanges like “I’m cold …” “Oh, you ARE not” impossible), but they are a neat thing to have in a language. In fact, markers like this (called “evidentials” in the linguistics literature) actually exist in many languages. When Elgin was constructing Láadan, she drew on aspects of natural languages she thought were “valuable and appropriate” to the job of expressing a woman’s perspective, but I suspect in many cases she incorporated features simply because they appealed to her. As she says, she created the “pejorative” marker ih (it helps turn bini , “gift,” into rabinilh , “a gift with strings attached”) after a similar marker in Navajo, because it “is something so very handy that I have always wished it existed in English.” She sounds less like a woman who has discovered a way to better express women’s perceptions than a linguist who has discovered another juicy tidbit on the ever-fascinating banquet table of natural languages. While her appropriation of the Navajo pejorative marker is justified by her overall goal of making attitudes usually conveyed by body language or tone of voice more explicit, when she lovingly picks it up and places it into her own language, she seems motivated less by scientific mission than by artistic vision. It is not a female thing to have in a language; it is an interesting thing to have.

Láadan never really took off. Small “working groups” formed here and there, but they dissolved as people got busy with other things. There was also a negative reaction to Láadan from a segment of the lesbian academic community who accused Elgin of being biased against lesbianism because she hadn’t included anything about it in the language. “The whole altercation,” she told me in an e-mail, “caused me great distress and sorrow. The absence of lesbian vocabulary and content was simply an accident of my personal circumstances. I was living way out in the country in rural Arkansas, totally isolated from the academic world and academic feminism. I was totally ‘ignorant’ about lesbianism and couldn’t have written about it even if I’d thought of it.” She offered to include vocabulary relevant to lesbianism in any future editions of the dictionary and solicited suggestions from her critics, but no further editions were published (the new vocabulary does appear in the online dictionary).

After ten years passed, and women had still not embraced Láadan or come up with another language to replace it, Elgin declared the experiment a failure, noting, with some bitterness, that Klingon (a hyper-male “warrior” language) was thriving. Still, she had found the challenge interesting and “well worth the effort.”

Bob LeChevalier, who discovered Láadan through his contacts in the science fiction community, found certain aspects of the language so interesting that he was inspired to adapt them for Lojban. After checking with Elgin to make sure she didn’t mind (she didn’t), the Lojbanists developed their own system of evidential markers, as well as a set of special indicators that greatly expanded the range of speaker emotions, attitudes, and intentions that could be expressed. Of course, they ran with it in the usual Lojban way and ended up with a system capable of distinguishing among hundreds, maybe thousands of feelings. Along with ui ([happiness] Yay!), u’u ([repentance] I feel guilty), it ([fear] Eek!), and .o’u ([relaxation] Phew!), there are compound indicators ranging from .uecu’i ([surprise][neutral] ho hum), to .o’unairo’a ([relaxation][opposite][social] I feel social discomfort), to .uiro’obe’unai ([happiness][physical][lack/need][opposite] Yay![physical] Enough!), something you might say after enjoying a big meal. As the Lojban grammar states, “We have tried to err on the side of overkill. There are distinctions possible in this system that no one may care to make in any culture.”

Strictly speaking, these indicators fall outside the realm of formal logic: their validity cannot be evaluated; there are no truth tables that can account for them. But the Lojbanists love them, and they have a lot of fun playing with them. So much fun that one of them proposed a new language called Cinban (from cinmo bangu , “emotion language”), which would just be English with the attitudinal indicators thrown in, something the Lojbanists had been doing casually for a long time. He set up a new Web forum in which “to practice .o’o [patience] using Cinban until I’m fully fluent .a’o [hopefully] in it. Anyone’s welcome .e’uro’a [suggestion, social] to join me, of course uenaidai [expectation, empathy].” Using the indicators often, and in a creative way, is a hallmark of Lojbanness—which is to say, something Lojban culture values highly.

Lojban culture? A language, of course, once it gets off the drawing board and into the hands of people who use it, can never be culture-free. Loglan, and Lojban after it, were bound to develop a culture of their own. They attracted a self-selecting group of people who already shared many of the same interests and thought about things in similar ways. As one of them put it in an early issue of the Loglanist , Loglan speakers “have a prior weird-ness that ruins any whorf-test.” To become a Loglanist, you had to, in a certain sense, already think like a Loglanist. James Cooke Brown did not see this as too much of a problem, though, because the experimental tests that were expected to eventually occur would be performed not on the Loglanists who had developed the language but on “normal” subjects, who would learn Loglan in the (culturally) sterile environment of the laboratory. Some Lojbanists still dream of the day when the laboratory tests will finally be implemented, but it is unclear whether even they themselves are capable of learning Lojban to a level of basic proficiency, much less any “normal” people.

Читать дальше