I was scheduled to give a talk on the history of invented languages (when I registered, the organizer discovered through my Web page that I was writing a book and invited me to give a presentation about it). I came armed with my own Lojban translation of Borges’s quotation about the futility of classifying the universe, the one I had translated into Wilkins’s language: “It is clear that there is no classification of the universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what thing the universe is.” Studying Lojban had given me the same unsettling feeling that I had experienced deep within the thickets of Wilkins’s tables—the sensation of being sucked into meaning quicksand, where the struggle for greater precision was not a lunge toward solid ground but a hopeless kicking and flailing that only pulled me in deeper.

But in Lojban it was worse. Not only did I have to pin down which translation I should use for content words like “clear,” “arbitrary,” and “reason” (is the best I can do for “arbitrary” really cunso —“ x is random/fortuitous/unpredictable under conditions y, with probability distribution z”?); I also had to grapple with little function words like “the,” “and,” “of,” and “no”—words for which Wilkins had supplied straightforward substitutes.

Then I had to deal with syntax. Until Loglan, invented languages had never been very explicit about how sentences should be put together. In philosophical languages like Wilkins’s, or symbol languages like Blissymbolics, once you had done the hard work of finding the appropriate concept words, you just arranged them in an English-Latin-type hybrid grammar. There was never a well-defined “correct” syntax for these languages. Esperanto developed a better-defined standard of proper sentence structure, but it came naturally through usage, and not because the inventor laid down the rules from the beginning. You don’t learn the rules of Esperanto; you intuit them from examples. When speaking Esperanto, I could draw on my general familiarity with European languages and wing it pretty successfully.

There is no winging it in Lojban. The language has an exhaustively defined syntax, and it is completely unambiguous. One must clearly specify the structure of the sentence as a whole, using various markers that serve, in effect, as spoken parentheses. There can be no confusion, for example, between an “ancient (history teacher)” and an “(ancient history) teacher” in Lojban. When you say “I saw the man with the binoculars” in Lojban, you can leave no doubt as to whether you had the binoculars or the man did. Lojban sentences have only one structural parse.

So you have to make sure it’s the one you really want. Composing a sentence in Lojban is like writing a line of computer code. Choose the wrong function, drop a variable, forget to close a parenthesis, and it doesn’t work. But how do you know it doesn’t work? At least when you write a computer program, you have a way to determine whether you’ve made a mistake: you hit enter, and the program doesn’t do what you wanted it to do. How do you sit down with a six-hundred-page book of grammatical rules and determine whether you’ve followed them correctly?

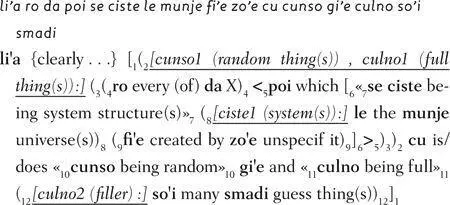

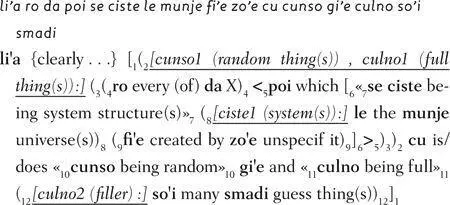

Fortunately, you can visit jboski , the online Lojban-to-English translator, and at least see if your Lojban sentence parses. If you’ve made any major errors, or left out a crucial structural element, you’ll get an error message. If you managed to create a valid Lojban sentence, you will get something like this, the product of my first (after several tries) successfully parsed translation of “It is clear that there is no classification of the universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures”:

I got a little thrill when my sentence returned this parse. It was the same thrill I would get during grad school, when, after a long night of beating my head against the keyboard trying to write a data-crunching program, a beautiful stream of output would finally pour down the screen like a light-dappled waterfall of celebratory champagne.

But was this parse cause for celebration? I wasn’t so sure. I knew that I had composed a grammatical Lojban sentence, but I couldn’t be certain it meant what I wanted it to mean. When I presented it to the Lojbanists at Logfest, I discovered that it didn’t. I had actually said that all classifications of the universe were random and full of people who guess. Smadi means “ x guesses y is true about subject z.” According to the syntax of my sentence, I was making a statement about the x argument—the guesser. What I wanted was they argument—the guess. I should have used sesmadi instead.

I didn’t feel too bad, though. Lojbanists are always making this kind of mistake. They are always making all kinds of mistakes. I know this because on the message boards where Lojban is used, hardly a sentence goes by that is not questioned or corrected—often by the very person who wrote the sentence. In fact, the main topic of Lojban conversation is Lojban itself. When one heated exchange (in English) led a commenter to write “Go fuck yourself!” in Lojban, it turned into a lengthy discussion of why he hadn’t said what he meant to say, and what the proper Lojban expression for the sentiment might be.

I didn’t see much live conversation at Logfest, but I did see a little. It goes very, very slowly. It’s like watching people do long division in their heads. Of course, the types of people who are attracted to Lojban are precisely the types who are good at doing long division in their heads. Almost everyone there had some kind of engineering or math background (except for one enthusiast who, being fifteen years old, couldn’t properly be said to even have a background). For dedicated Lojbanists, only part of the difficulty of speaking Lojban comes from the mental effort involved in keeping track of functions and variables. The rest of the difficulty comes from having to hyper-vigilantly guard their Lojban against the influence of English.

The temptation is there, for example, to use the word gunka (work) in a sentence like “This phone doesn’t work.” But gunka means “ x labors/works on y with goal/objective z.” It doesn’t cover the English sense of “work” meaning “to function.” It would likewise be inappropriate to use dizlo (low) to say you’re feeling low, because dizlo only means low “as compared with baseline/standard height z.” The metaphorical extension of lowness to emotions doesn’t hold in Lojban. There is a Lojban word for these kinds of mistakes— malglico (damned English!). Malglico is what happens when you let the assumptions of English creep into your Lojban.

And this must be avoided in Lojban, because to remain valid in a test of the Whorfian hypothesis, it must remain culturally neutral. In terms of vocabulary, this means that definitions should be unclouded by connotations and metaphorical extensions that may not be shared from culture to culture. In terms of grammar, this means that it should have the resources to express the range of distinctions that languages express, including distinctions that English might not have. For example, English does not make the grammatical distinction between alienable and inalienable possession, but other languages do. In the Austronesian language Mekeo, you express possession one way if the possessed thing could potentially be transferred to someone else ( e?u ngaanga : “my canoe”) and a different way if it cannot ( aki-u : literally “brother-my,” so “my brother”). If it is true that the difference in the grammatical treatment of possession between English and Mekeo gives rise to some difference in worldview between the two cultures, Lojban doesn’t want to force Mekeo speakers to blur the distinction, thereby forcing them to take on the English view of possession. In Lojban you can make the distinction, but you are not required to (because that would be forcing the Mekeo worldview on English speakers). However, if the English speaker chooses to use the neutral form, he should be aware that if he introduces someone as le mi bruna (the-somehow-associated-with-me brother), he has said only that that person is a brother (maybe his own, maybe someone else’s) who has some connection with him. If he assumes he has said “my brother” in the commonly understood English sense, he is being rather malglico .

Читать дальше