Bliss was fond of saying, “The greatest hindrance to Blissym-bolics is the fact that I am still alive.” Most of the time he meant this as an accusation against society and its inability to notice genius until it no longer walks among them. But sometimes he seemed to mean it as self-reproach, an admission that he was his own worst enemy. He angered and drove away almost everyone who could have done him any good.

And yet, in a few, he inspired a devoted kind of loyalty—partly based on his manic charisma, and partly based on pity. Shirley never expressed more than mild exasperation with him. On his last trip to Toronto, they spent their days together in a room full of administrators and lawyers, going through legal discovery for his case against her work. At night, she went to his seedy hotel room to help him put drops in his ears for a medical condition. When I asked her how that made any sense, she answered, “Well, he had no one else.”

Bliss spent the money on a big publication run of his own Blissymbols teaching manual. It is the sharpest looking of all his publications—a bright red hard-vinyl cover over 564 high-quality card-stock pages held together in a two-ring binder. It is professionally illustrated, and all the symbols are drawn to his specifications. The content, however, is the same old classic Bliss—blustery and preposterous. Here is how he advises teaching the symbol for steam:

Put a saucepan or a kettle on the stove and when the steam comes out let your handicapped child put its finger near the steam. Of course, it will get slightly burned, but it will be a lesson for life what steam really is and why it is the opposite of rain, which is usually rather cold or slightly warm.

Most of the books were destroyed in a fire after Bliss died in 1985. Douglas Everingham, a local Sydney doctor and politician, was named one of the executors of what was left. Everingham, himself interested in the international language cause, had been an early supporter of Bliss’s work and had done what he could in the 1970s, during his term as national minister of health, to promote Blissymbolics (at great risk to his own reputation). Bliss, of course, thought Everingham didn’t try hard enough and once showed up at a public rally where he was campaigning for re-election and heckled him, crying, “Down with Everingham!” and worse.

Everingham told me by e-mail that he still thought kindly of Bliss, and encouraged me to be charitable toward him as well. He reminded me that Bliss was a Holocaust survivor, a refugee, an immigrant; Bliss had seen terrible things, and he really did believe he had invented a solution, a way to ensure those things would never happen again.

But, in looking through Bliss’s writings, I found that he did have his moments of doubt. Buried in one of his books, in a rant about psychologists and how they are always trying to read into things, is the following passage:

Take Bliss, the author of this book. He thinks that his work is motivated by his conscience, that he slaves for humanity. But it may be only a craving for the limelight of public acclaim. He rises in defence of the children of mankind (so he thinks) when he attacks the teachers. But it may be only envy and enmity and rage about their rejection of his work (which they didn’t even bother to examine).

He thinks his invention will revolutionize the 21st century. The hell it will! The teachers will be adamant. So he cries, “To dream the impossible dream, to beat the unbeatable foe, etc., etc.” feeling himself a pioneer and martyr rolled in one.

Well, what motivates him really?

He stops there.

James Cooke Brown and the Language of Logic

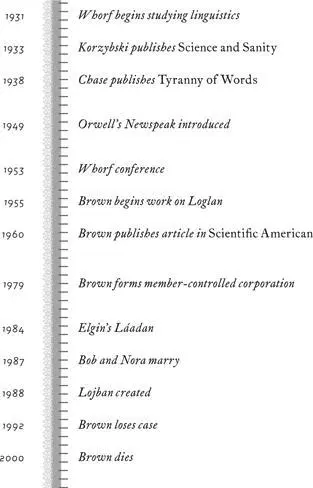

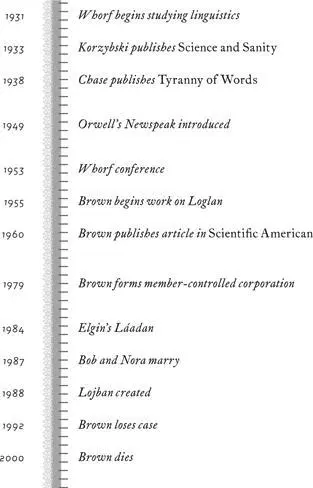

Blissymbolics and aUI and the few other pictographic languages of the post-Esperanto era hardly constituted a movement , but they did reflect a widespread popular preoccupation with, as the title of one 1938 best seller called it, “the tyranny of words.” Both Bliss and Weilgart advertised their projects not just as a way for people of different language backgrounds to communicate with each other but as a way to uncover the truths that our natural languages hid or distorted. They worked on the assumption that language warped the mind, and that assumption was not just some crazy outsider philosophy. It was very much a part of the general intellectual climate from the 1930s to the 1950s, when Bliss and Weilgart were developing their systems.

Of course, the Nazi and Soviet propaganda machines provided dramatic evidence for the pernicious power of language, but the “tyranny of words” idea went beyond the claim that bad people sometimes used language to bad ends. It suggested that all of us, every day, were being misled, not by lies told by others, but by our own habits of thinking, as conditioned by the very structure of our languages.

This idea had become popular even before the war. In their influential book, The Meaning of Meaning (1923), C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards blamed all sorts of confusion on “the superstition that words are in some way parts of things or always imply things corresponding to them”—the “Word Magic” problem that Ogden later proposed to solve with his Basic English. Ten years later Count Alfred Korzybski published his Science and Sanity , a dense, jargon-filled tome on the ways in which language “enslaves” us by conditioning our brains to perceive a false reality. More people probably claimed to have read it than actually did—even his followers called the azure-tinted volume “the blue peril”—but Korzybski’s ideas, as interpreted by popularizers like Stuart Chase (of the previously mentioned Tyranny of Words ) and S. I. Hayakawa (of the 1941 Book-of-the-Month Club selection Language in Action ), rippled through the culture. For a time, any cocktail party guest with pretensions to erudition could pepper his conversation with a “general relativity” here, a “neuro-semantic reaction” there, a melodious “Korzybski” or two to tie it all together, and he would be rewarded with some knowing, serious head nodding.

In the halls of mainstream academia, however, Korzybski’s name got a different reaction. He was an independent scholar without professionally recognized expertise in any of the fields he drew on in creating his boastful, sprawling theory of everything. He published his books and ran his seminars under the rubric of his own Institute of General Semantics, where he promoted techniques for overcoming the thinking errors caused by language—beware of the verb “to be” (“Is-ness is insanity,” he liked to say), mentally subscript the objects you talk about (to remind yourself that there is only pencil 1, pencil 2, pencil 3, and so on and no abstraction “pencil” that covers all cases), and frequently insert an “etc.” (to remind yourself that there is always more to the story than your words would have you believe).

It didn’t help that his seminars had the flavor of a tent revival, complete with emotional manipulation disguised as object lessons (he liked to bring a female student up to the stage and slap her face, then tell the audience that their horrified reaction was “unjustified, as what they have seen turned out to be merely a scientific demonstration of the mechanism of identification”) and testimonials. People in various professions claimed that training in general semantics (as Korzybski’s discipline came to be called) could solve an astonishing array of problems: businessmen said it saved their clients' money; psychiatrists said it cured alcoholism, homosexuality, frigidity, and nymphomania; teachers said it cured reading problems, stuttering, and stage fright; a dentist even said it helped keep fillings in place.

Читать дальше