For example, Bliss’s symbol for water is Weilgart’s symbol for sound. For Weilgart, water is not a primitive but a complex concept:

The explanation is that water is the liquid ( jE , matter that “stands even, when at rest”) of greatest quantity.

For Bliss, sound is not a basic primitive but a complex concept,  —an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”

—an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”

Weilgart’s image of water refers to how it looks when it is level, and Bliss’s refers to how it looks when it has waves in it. Bliss’s image of sound refers to the organ that receives it, and Weilgart’s refers to the “wave” physics of its transmission. Who has the truth? Whose representation is more “natural”?

If two men who come from the same place and speak the same language can’t even agree with each other about the “true” representation of anything, how can either one of them stake a claim on universality? The act of understanding a sentence in either system is an act of figuring out one man’s opinions, of guessing one man’s intentions. These languages are about as opposite of universal as you can get. They require mind reading, a task considerably more difficult than, say, learning French.

Imagistic symbolism can transmit meaning, but in such a vague and open-ended way that it makes a terrible principle on which to build a language. This is why there are no languages, and no writing systems, that operate on such a principle.

This includes sign languages, which are assumed by many to be a sort of universal pantomime. In fact sign languages differ considerably from country to country, so much so that in the 1950s, the newly formed World Federation of the Deaf assigned a committee to look into the matter of developing an auxiliary sign standard that could be used at the federation’s world congress and other international deaf events. The result, finally published in 1975, was Gestuno, the Esperanto of sign language.

Sign languages differ for the same reason spoken languages differ—they evolved naturally, from communities of people interacting with one another. Wherever deaf people have come together in groups, whether because they lived in places with a high incidence of genetic deafness or because they were brought together in institutions or schools, they have spontaneously developed a sign language. These languages may have their origins in gestures of “acting things out”—a type of vague, partial communication—but over time set meanings developed, means of marking grammatical distinctions became fixed, and they turned into real languages, systems of full communication.

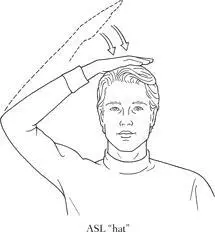

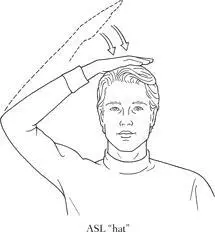

Signs mean what they mean by conventional agreement, and different communities of signers have different agreements. In American Sign Language (ASL), for example, the sign below means “hat,” not because it looks like a hat being placed on the head, but because the community of users of ASL agree that it means “hat.”

Users of Nepali Sign Language (NSL) have a different agreement: a sign that looks exactly the same means “well done.”

Does this sign “look like” a pat on the head for a job well done or a hat being placed on the head? It doesn’t really matter. What matters is that Nepalese signers agree that it’s the sign for “well done” and American signers agree that it’s the sign for “hat.” The meaning isn’t dependent on the imagery.

Many signs do, in some sense, “look like” what they mean, but just because you can come up with an explanation for why a sign has the form it has does not mean the sign gets its meaning by virtue of that explanation. This is true for spoken words as well. The word “breakfast,” for example, has a motivated form, inspired by the idea of breaking a fast, something you do in the morning when you eat after going eight hours or so without food. But “breakfast” does not mean “to break a fast.” It means “morning meal,” or, in the case of “breakfast anytime” diners, a meal consisting of eggs or pancakes. “Breakfast” gets its meaning from the way “breakfast” is used, not from the fact that it was once formed from the words “break” and “fast.” (Therefore it doesn’t matter that the “break” in “breakfast” has come to be pronounced “brek.” You don’t need to recognize the motivation for the word in order to understand it.)

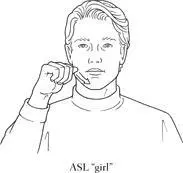

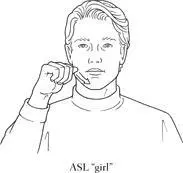

Likewise, the ASL sign for “girl,” which traces a line on the cheek, gets its meaning through conventional usage, not from the fact that it was motivated by the image of a bonnet string. (Therefore it doesn’t matter that girls no longer wear bonnets.)

Gestuno, like most international language schemes, was a big flop. The committee had drawn from existing sign languages, trying to pick the most iconic signs, but without favoring any one country too much. Deaf people complained that the signs that had been chosen weren’t easy enough to understand. Furthermore, Gestuno was only a lexicon, not a grammar, so there were no explicit guidelines for putting sentences together. At the 1979 World Deaf Congress in Bulgaria, the first congress to provide Gestuno interpretation of the presentations, the interpreters simply stuck Gestuno signs into (spoken) Bulgarian sentence structures (sign languages do not follow the same word order or grammar as their surrounding spoken languages). No one understood what was going on, and Gestuno never recovered from the fiasco.

Something else took its place—a spontaneous sort of pidgin signing now called International Sign. It had actually been around long before Gestuno. Whenever deaf people of different sign language backgrounds get together at international events (like the Deaf Olympics, which began in the 1920s), they quickly find a way to communicate with one another. They sign more slowly, gesture, and repeat information in multiple ways, and pretty soon they come to a sort of miniature, incomplete, conventional agreement. They negotiate a standard, but one that is less reliable than any full sign language.

However, that standard, and a pretty good level of communication, is achieved far more quickly and easily than it ever could be between people who speak different spoken languages. That is because while the iconic imagery is not the primary principle on which sign languages depend, it is undeniably there, and it has the potential to be exploited. Spoken languages have this potential as well (something can last a “long” time or a “loooooooong” time) but a whole lot less of it.

Imagery, in signs or in symbols, isn’t suitable for communication on its own. It must be interpreted, its meaning guessed at. But in a situation where the guesses can be constrained, where two people can use context and feedback from each other to put a limit on the possible interpretations, it is extremely useful. The teachers at the OCCC understood this, and what they did with the children was set up just such a situation. When a child wanted to say “dream” but did not have a symbol for it on her board, she pointed to “sleep + think.” Her teacher guessed from the context that she meant “dream,” and the child confirmed that guess. If a child tried a combination and the teacher guessed wrong, the teacher could take another guess, or the child could try a different approach. Communication had always been a guessing game for these children, but before Blissymbols they had no way to constrain the guesses. If a child had needs-based pictures to point to, he might have tried to say “dream” by pointing to a picture of a bed. Then the adult would ask, “Do you want to go to bed? Do you want to get your pillow? Is there a problem in your bedroom?” and the child would have no power to direct the line of questioning. When the children learned Blissymbols, and a method for representing abstract concepts through combination, they finally had a way to actively put limits on interpretation.

Читать дальше

—an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”

—an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”