RAF crew and Guy Gibson making a fuss of their black Labrador dog, Nigger, who is wearing an Iron Cross

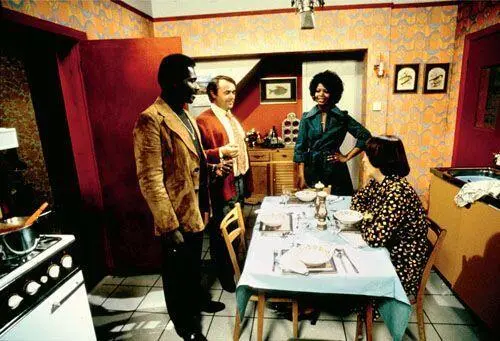

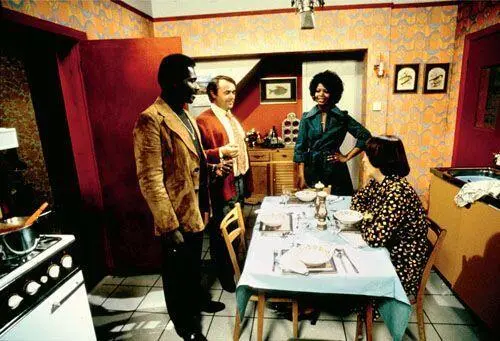

Racial linguistic sensibility is clearly not so acute in Britain, where society was largely white until the 1940s. Mass Afro-Caribbean immigration began after the Second World War, but it took decades before the word nigger was generally accepted as a racial slur. Love Thy Neighbour was a sitcom on ITV in the 1970s about a white family and a black family who lived next door to each other. Eddie, the white male character, talked about ‘sambos’ and ‘nig-nogs’. The scriptwriters claimed that Love Thy Neighbour was an attempt to address some of the issues raised by a growing immigrant population in Britain. The characters may have been racist, they argued, but the show wasn’t.

Black and gay stand-up comedian Stephen K. Amos was a schoolboy in south London when Love Thy Neighbour was broadcast. ‘I’d go to school on the Monday and be called a nig-nog because they’d see it on the show … I didn’t know I was a nig-nog until my classmates told me I was.’

Love Thy Neighbour , 1972

The interesting thing about today’s taboo words is that it’s seen as okay to use them if you’re part of the particular community. So Jews are allowed to say kyke ; Stephen Amos is gay and feels comfortable about using the word queer . A lot of black comedians like the American Chris Rock use the n-word quite freely, and there’s even a group called NWA, Niggers with Attitude. Stephen says he doesn’t use the n-word personally but understands why others might want to reclaim the word. What’s more important for him is that taboo words cause comedians to think before they speak.

‘When people say political correctness has gone mad, I really get offended by that term because I don’t think it’s being politically correct if you have to think before you speak, if you have to think before offending people. If you’re a clever comedian and you want to upset the apple cart then, yes, do that, but do it in a way which makes us all think, not just by throwing in a word or having a go at a community or at disabled kids. If there isn’t a purpose or a point, there’s no point, because we could all do that.’

Language is in a constant state of change and reinvention, and slang plays a vital role in this evolution. Slang is described in early editions of the Oxford English Dictionary as the ‘language of a low and vulgar type … consisting either of new words or of current words employed in some special sense’. The origin of the word slang is unknown. It doesn’t show up until the middle of the eighteenth century, when it was used to refer to the ‘special vocabulary of tramps or thieves’. Before then it was called cant or vulgar language .

Street slang, rhyming slang, back slang, teenage slang, text slang — there’s an abundance of slang in the English language, and the strong feelings it generates are nothing new. From the sixteenth century onwards, people were railing against use of the vulgar tongue. In 1621, John Milton’s headmaster, Alexander Gil, wrote about the cant speech of ‘the dirtiest dregs of the wandering beggars’. In his study of grammar and dialects, Logonomia Anglica , he described cant as ‘that poisonous and most stinking ulcer of our state’.

The satirist Jonathan Swift was a passionate advocate of the need to purify the English language. In an article published in the Tatler in 1710 he attacked what he called ‘the continual corruption of our English tongue’, not by the common people but by the writers and poets of the age. Swift denounced the use of abbreviations, in which only the first part of a word was used, and also:

the choice of certain words invented by some pretty fellows: such as banter, bamboozle, country put, and kidney, as it is there applied; some of which are now struggling for the vogue, and others are in possession of it. I have done my utmost for some years past to stop the progress of mobb and banter, but have been plainly borne down by numbers, and betrayed by those who promised to assist me.

Swift clearly failed to stop the entry of words like mob (from mobile vulgus , the Latin for fickle crowd) and banter into our everyday language.

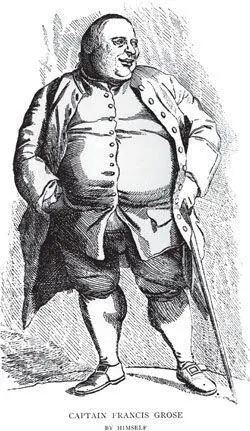

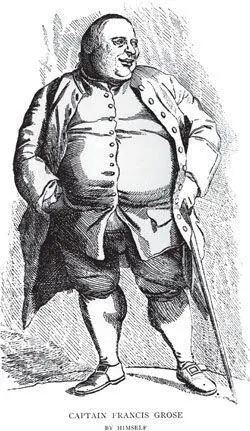

The first substantial dictionary of slang, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue , was published in 1785 by Francis Grose. He was a former soldier, innkeeper and champion drinker who collected slang from all corners of society — sailors, tradesmen, prostitutes, pickpockets and craftsmen. He and his assistant are said to have walked the slums of London at night, noting down the cant words spoken in the drinking dens and brothels. His dictionary included over 3,000 entries. Some of them are familiar — hen-pecked, topsy-turvey, brat, sheepish (for bashful) and carrots (for red hair). Others are, rather sadly, obsolete. Words like circumbendibus (a wandering path or story) or scandalbroth (tea).

What Grose calls vulgar, we would probably call slang. His dictionary meaning for devilish , for instance, reads: ‘an epithet which in the English vulgar language is made to agree with every quality or thing; as, devilish bad, devilish good; devilish sick, devilish well; devilish sweet, devilish sour; devilish hot, devilish cold, &c. &c.’ Many of the words reflected the seamier side of life. A covent garden nun was a prostitute, and the delightful-sounding scotch warming pan was a word for ‘a wench, also a fart’. There are plenty of rude words. S hag, hump and screw are all there for copulation. Less familiar are bum fodder for toilet paper and double jugg for a man’s bottom. And there’s one listed simply as ‘c — t: a nasty name for a nasty thing’; elsewhere he refers to it as ‘the monosyllable’.

Francis Grose created the first dictionary of slang in 1785

Unlike Swift, Grose believed that the rich abundance of slang words in the English language was something to be celebrated: ‘The freedom of thought and speech, arising from, and privileged by, our constitution, gives a force and poignancy to the expressions of our common people, not to be found under arbitrary governments.’

There’s a fascinating postscript to this larger-than-life character. Grose met the Scottish poet Robert Burns when he was in Scotland, drawing sketches and collecting material for a book on local antiquities. They got on famously — Burns wrote: ‘I have never seen a man of more original observation, anecdote and remark’ — and Grose agreed to include a drawing of Alloway Kirk in his forthcoming volume, if Burns would provide a witch tale to accompany it. In 1790 Burns sent him the rhyming tale of ‘Tam O’Shanter’ — arguably one of the best examples of narrative poetry in the English language.

Costermongers loved to use the secret language of back-slang

Читать дальше