Nautical terms have permeated our everyday language. Some of the expressions are to do with the technical side of sailing — ship shape, know the ropes, keel over, be on an even keel, sail close to the wind, take the wind out of someone’s sails, make heavy weather, try a different tack, give someone leeway, make headway, give someone a wide berth, trail in someone’s wake .

Other naval phrases are hidden and need some unpicking. To feel groggy comes from grog , the sailor’s daily ration of watered-down rum. If you’ve drunk too much and you’re three sheets to the wind, then you’re in the same condition as a ship whose lines holding the sails in place are loose — you shudder and roll. Down the hatch is another drinking term which comes from the cargo being lowered through the hatch into the ship’s hold. Pipe down , meaning to be quiet, was the signal at the end of the day for lights out on board. The phrase no room to swing a cat is thought to refer to naval floggings using a cat (cat o’nine tails) in the cramped spaces of the old sail ships. Someone in low spirits, who’s in the doldrums , is experiencing what sailors called the windless, becalming area near the equator. And when the barefooted sailors were called on deck for inspection, they had to line up in neat rows along the seams of the wooden planks and toe the line .

The problem with jargon is when it leaves the confines of a particular profession or expertise and is used to communicate with the wider world. That’s when the definition of jargon changes.

Chaucer used the word to mean the twittering or chattering of birds, and that’s exactly how specialized language of the expert sounds to the punter — a meaningless twitter.

Doctors need to be able to communicate quickly and effectively with other medical professionals. But unlike sailors on a boat or a sparks in a film crew, they have to talk to people outside their specialized group — their patients. It may be a bilateral probital haematoma to them; to us, it’s a black eye. Myocardial infarction? That’s a heart attack.

Most medical terminology derives from Latin or Greek, so unless you’ve studied the Classics, jargon ‘clues’ like cardio for heart, haema for blood, tachy for fast, hypo for low and hyper for high are meaningless.

In our more patient-centred world, doctors have got much better at dropping the medical jargon and speaking to patients in a language they can understand. They’re learning to be more bilingual, shifting from seborrhoeic dermatitis to a touch of dandruff .

Many of the complicated medical terms have been replaced by another form of jargon — the medical acronym. It’s clearer and quicker to use abbreviations for long-worded conditions. DVT is much simpler than deep vein thrombosis or URI for upper respiratory infection; sometimes an abbreviation is used to avoid upset, as in DNR for ‘do not resuscitate’. The acronym is also used as a secret code between doctors to talk candidly about the patient, although legislation allowing patients access to their own medical notes may curtail the practice. These acronyms, however, show no evidence of a cramping of style.

FLK: funny-looking kid

ABITHAD: another blithering idiot — thinks he’s a doctor

ART: assuming room temperature (recently deceased)

FFFF: female, fat, forty and flatulent

GOK: God only knows

GLM: good-looking mum

TTGA: told to go away

MFC: measure for coffin

NFWP: not for War and Peace (dying so no point in starting a long book)

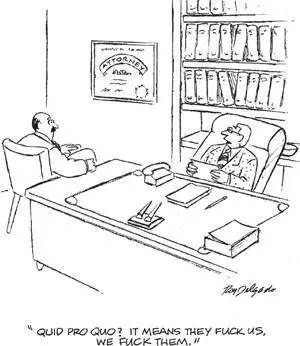

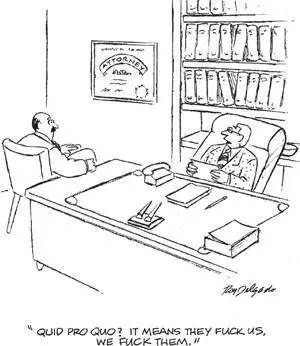

Lawyers too are renowned for baffling their clients with a prioris, ibids, idems and obscure case references. The critic A. P. Rossiter wrote in Our Living Language in 1953: ‘It strikes everyone as an extreme case of the evils of jargon when a man is tried by a law he can’t read, in a court which uses a language he can’t understand.’

In English civil courts, attempts have been made to demystify the language with the abolition of some of the most archaic legal jargon and Latin maxims. Since 1999, people bringing cases to court are claimants , not plaintiffs , a writ is called a claim form , and minors are children. The new legal terms are designed to help people understand the law, so in camera has become private , a subpoena is a witness summons , and an Anton Piller , named after the plaintiff (sorry, claimant) in a court case in the 1970s, is now simply a search and seizure order.

Legalese, the term for legal writing that’s designed to be difficult for the layman to read or understand, may be harder to eradicate. The long-winded sentences, countless modifying clauses and complex and often unnecessary vocabulary have been annoying non-lawyers for centuries. Four hundred years ago, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote had this to say about legalese: ‘But do not give it to a lawyer’s clerk to write, for they use a legal hand that Satan himself will not understand.’

Lawyers are renowned for baffling their clients

Lawyers want to write contracts which are legally binding and cover all possible contingencies but even they often have trouble decoding the legalese. Documents are peppered with subsequent to and forthwith and double-barrelled keep and maintain and goods and chattels . Campaigners for the use of plain language give this example of legalese:

Upon any such default, and at any time thereafter, Secured Party may declare the entire balance of the indebtedness secured hereby, plus any other sums owed hereunder, immediately due and payable without demand or notice, less any refund due, and Secured Party shall have all the remedies of the Uniform Commercial Code.

The plain-language alternative? ‘If I break any of the promises in this document, you can demand that I immediately pay all that I owe.’

Plain English in the Workplace

The battle for plain English in the world of politics and government has been raging longer than you might think. In 1948, a British civil servant, Sir Ernest Gowers, was invited by HM Treasury to produce a manual for government officials on how to avoid over-elaborate writing. Plain Words, a Guide to the Use of English was so successful that Gowers followed it with The ABC of Plain Words and The Complete Plain Words .

Sir Ernest cites the example of a circular sent from a government department to its regional offices which began: ‘The physical progressing of building cases should be confined to … ’ Sir Ernest writes:

Nobody could say what meaning this was intended to convey unless he held the key. It is not English, except in the sense that the words are English words. They are a group of symbols used in conventional senses known only to the parties to the convention.

A member of the department explained to him that the phrase meant going to a building site to see how many bricks had been laid since the last visit. ‘It may be said that no harm is done,’ continues Sir Ernest,

because the instruction is not meant to be read by anyone unfamiliar with the departmental jargon. But using jargon is a dangerous habit; it is easy to forget that the public do not understand it, and to slip into the use of it in explaining things to them. If that is done, those seeking enlightenment will find themselves plunged in even deeper obscurity.

Читать дальше