“The Dutch and their vla …” Silletti speaks it like a curse word. “For me it’s not food. You don’t need teeth or saliva!”

Oddly, the cluster of Wageningen-area universities and research facilities known as “Food Valley” is the home of the foremost expert on the physics of crunchy food, as well as a man who knows more about chewing than anyone else in the world. I am meeting them both tomorrow, at the Restaurant of the Future. This is a cafeteria at Wageningen University where hidden cameras allow researchers to gauge how, say, lighting affects purchasing behavior, or whether people are more likely to buy bread if you let them slice it themselves. Silletti says she won’t eat there.

“Because of the cameras?”

“Because of the food.”

7. A Bolus of Cherries

LIFE AT THE ORAL PROCESSING LAB

WHEN I TOLD people I was traveling to Food Valley, I described it as the Silicon Valley of eating: fifteen thousand scientists dedicated to improving or, depending on your sentiments about processed food, compromising the quality of our meals. At the time I made the Silicon Valley comparison, I did not expect to be served actual silicone. But here it is, a bowl of rubbery white cubes the size of salad croutons. Andries van der Bilt brought them from his lab in the brusquely named Department of Head and Neck, at the nearby University Medical Center Utrecht.

“You chew them,” he says.

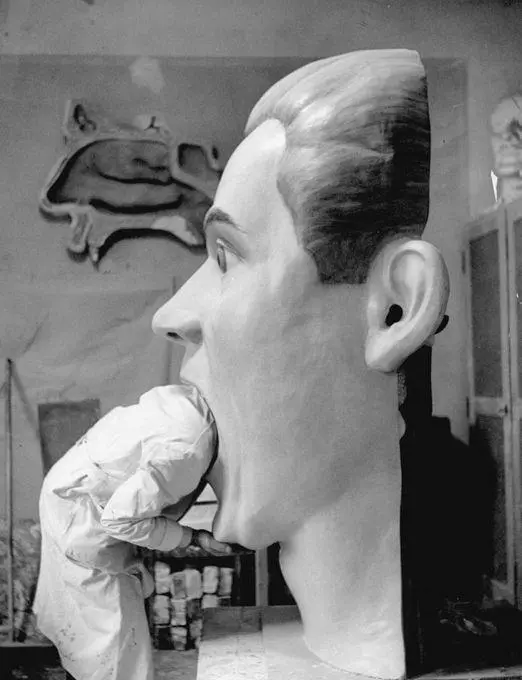

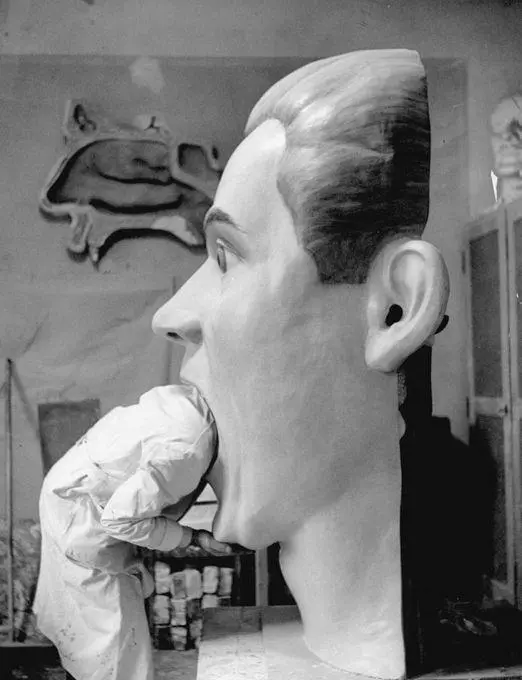

Van der Bilt has studied chewing for twenty-five years. If a man can be said to resemble a tooth, van der Bilt is a lower incisor, long and bony with a squared-off head and a rigid, straight-backed way of sitting. It’s between meals now in the camera-rigged Restaurant of the Future. The serving line is unstaffed, and the cash registers are locked. Outside the plate-glass windows, it’s snowing again. The Dutch pedal along on their bicycles, seeming daft, or photoshopped.

The cubes are made of a trademarked product called Comfort Putty, more typically used in its unhardened form for taking dental impressions. Van der Bilt isn’t a dentist, however. He is an oral physiologist. He uses the cubes to quantify “masticatory performance”—how effectively a person chews. Research subjects chew a cube fifteen times and then return it in its new, un-cube-like state to van der Bilt, who pushes it through a set of sieves to see how many bits are fine enough to pass through.

I take a cube from the bowl. Van der Bilt, the cameras, and emotion-recognition software called Noldus FaceReader watch me chew. By tracking facial movements, the software can tell if customers are happy, sad, scared, disgusted, surprised, or angry about their meal selections. FaceReader may need to add a special emotion for people who have chosen to have the Comfort Putty. If you ever, as a child, chewed on a whimsical pencil eraser in the shape of an animal, say, or a piece of fruit, then you have tasted this dish.

“I’m sorry.” Van der Bilt winces. “It’s quite old.” As though fresh silicone might be better.

The way you chew is as unique and consistent as the way you walk or fold your shirts. There are fast chewers and slow chewers, long chewers and short chewers, right-chewed people and left-chewed people. Some of us chew straight up and down, and others chew side to side like cows. Van der Bilt told me about a study in which eighty-seven people came into a lab and chewed an identical amount of shelled peanuts. Though all had a full complement of healthy teeth, the number of chews ranged from 17 to 110. In another project, subjects chewed seven foods of widely varying textures. The best predictor of how long they chewed before swallowing wasn’t any particular attribute of the food. The best predictor was simply who’s chewing. Your oral processing habits are a physiological fingerprint. As with the finger kind, most of us have no idea what ours look like. [51] Fingerprints come in three types: loop (65 percent), whorl (30 percent), and arch (5 percent). Oral processing styles for semisolid foods come in four: simple (50 percent), taster (20 percent), manipulator (17 percent), and tonguer (13 percent). Thus the millions of variations that make you the unique and delightful custard-eater and fingerprint-leaver that you are.

We couldn’t pick our own chewing mouths out of a lineup, although it would be interesting to try.

Van der Bilt studies the neuromuscular elements of chewing. You often hear about the impressive power of the jaw muscles. In terms of pressure per single burst of activity, these are the strongest muscles we have. But it is not the jaw’s power to destroy that fascinates van der Bilt; it is its nuanced ability to protect. Think of a peanut between two molars, about to be crushed. At the precise millisecond the nut succumbs, the jaw muscles sense the yielding and reflexively let up. Without that reflex, the molars would continue to hurtle recklessly toward one another, now with no intact nut between. To keep your he-man jaw muscles from smashing your precious teeth, the only set you have, the body evolved an automated braking system faster and more sophisticated than anything on a Lexus. The jaw is ever vigilant. It knows its own strength. The faster and more recklessly you close your mouth, the less force the muscles are willing to apply—without your giving it a conscious thought.

You can witness the protective cutout reflex by hooking up a person’s jaw muscles to an electromyograph. The instant something hard gives way, the readout of electrical activity goes briefly flat. “The silent period, they call it,” van der Bilt says. It seems like a term kindergarten teachers might use, or people at a Quaker meeting. All these years, I’ve had it backward. Teeth and jaws are impressive not for their strength but for their sensitivity. Chew on this: Human teeth can detect a grain of sand or grit ten microns in diameter. A micron is 1/25,000 of an inch. If you shrank a Coke can until it was the diameter of a human hair, the letter O in the product name would be about ten microns across. “If there’s some earth in your salad, for instance, you notice immediately. It warns you for the wrong things.” Van der Bilt did the experiment himself. “We took some vla…” Custard! In the Netherlands, vla is never far from where you are. “We put some plastic grains of various sizes in it…”

Van der Bilt stops himself. “I don’t know if you want to hear these things.” He has a tentative, apologetic manner of speaking, like a man accustomed to feeling that his audience, at any moment, is about to make an excuse and get up to go. Earlier he told me that his unit at Utrecht is slated to close when he retires, in a year. “There isn’t,” he said, “enough interest.”

I think it may be something else.

THE STUDY OF oral processing is not just about teeth. It’s about the entire “oral device”: teeth, tongue, lips, cheeks, saliva, all working together toward a singular unpicturesque goal: bolus formation. The word bolus has many applications, but we are speaking of this one: a mass of chewed, saliva-moistened food particles. Food that is in—as one researcher put it, sounding like a license plate—“the swallowable state.” [52] I nominate Rhode Island.

I don’t think the scientists are uninterested. I think they may be disgusted. This is a job where on any given day, you may find yourself documenting “intraoral bolus rolling” or shooting magnified close-ups of “retained custard” with the Wageningen University tongue-camera. Should you need to employ, say, the Lucas formula for bolus cohesiveness, you will need to figure out the viscosity and surface tension of the moistening saliva as well as the average radius of the chewed food particles and the average distance between them. To do that, you’ll need a bolus. You’ll need to stop your subject on the brink of swallowing and have him, like a Siamese with a hairball, relinquish the mass. If the bolus in question is a semisolid—yogurt and vla are not chewed, but they are “orally manipulated” and mixed with saliva—the work is yet less beautiful. As evidenced by this caption in a textbook chapter by my host René de Wijk: “Figure 2.2. Photographs of spat-out custard to which a… drop of black dye has been added.”

Читать дальше