Function was not hinted at in Mrs. Claflin’s educational torso man. Interior surfaces were hidden. The small intestine and colon were presented as a single fused ravelment, like a brain that had been thrown against the wall. Yet I owe the guy a debt of thanks. To venture beyond the abdominal wall, even a plastic one, was to pull back the curtain on life itself. I found it both appalling and compelling, all the more so because I knew a parallel world existed within my own pinkish hull. I mark that fifth-grade classroom as the point at which curiosity began to push aside disgust or fear or whatever it is that so reliably deflects mind from body.

The early anatomists had that curiosity in spades. They entered the human form like an unexplored continent. Parts were named like elements of geography: the isthmus of the thyroid, the isles of the pancreas, the straits and inlets of the pelvis. The digestive tract was for centuries known as the alimentary canal. How lovely to picture one’s dinner making its way down a tranquil, winding waterway, digestion and excretion no more upsetting or off-putting than a cruise along the Rhine. It’s this mood, these sentiments—the excitement of exploration and the surprises and delights of travel to foreign locales—that I hope to inspire with this book.

It may take some doing. The prevailing attitude is one of disgust. There are people, anorexics, so repulsed by the thought of their food inside them that they cannot bring themselves to eat. In Brahmin Hindu tradition, saliva is so potent a ritual pollutant that a drop of one’s own spittle on the lips is a kind of defilement. I remember, for my last book, talking to the public-affairs staff who choose what to stream on NASA TV. The cameras are often parked on the comings and goings of Mission Control. If someone spots a staffer eating lunch at his desk, the camera is quickly repositioned. In a restaurant setting, conviviality distracts us from the biological reality of nutrient intake and oral processing. But a man alone with a sandwich appears as what he is: an organism satisfying a need. As with other bodily imperatives, we’d rather not be watched. Feeding, and even more so its unsavory correlates, are as much taboos as mating and death.

The taboos have worked in my favor. The alimentary recesses hide a lode of unusual stories, mostly unmined. Authors have profiled the brain, the heart, the eyes, the skin, the penis and the female geography, even the hair, [3] The Hair , by Charles Henri Leonard, published in 1879. It was from Leonard that I learned of a framed display of presidential hair, currently residing in the National Museum of American History and featuring snippets from the first fourteen presidents, including a coarse, yellow-gray, “somewhat peculiar” lock from John Quincy Adams. Leonard, himself moderately peculiar, calculated that “a single head of hair of average growth and luxuriousness in any audience of two hundred people will hold supported that entire audience” and, I would add, render an evening at the theater so much the more memorable.

but never the gut. The pie hole and the feed chute are mine.

Like a bite of something yummy, you will begin at one end and make your way to the other. Though this is not a practical health book, your more pressing alimentary curiosities will be addressed. And some less pressing. Could thorough chewing lower the national debt? If saliva is full of bacteria, why do animals lick their wounds? Why don’t suicide bombers smuggle bombs in their rectums? Why don’t stomachs digest themselves? Why is crunchy food so appealing? Can constipation kill you? Did it kill Elvis?

You will occasionally not believe me, but my aim is not to disgust. I have tried, in my way, to exercise restraint. I am aware of the website www.poopreport.com, but I did not visit. When I stumbled on the paper “Fecal Odor of Sick Hedgehogs Mediates Olfactory Attraction of the Tick” in the references of another paper, I resisted the urge to order a copy. I don’t want you to say, “This is gross.” I want you to say, “I thought this would be gross, but it’s really interesting.” Okay, and maybe a little gross.

1. Nose Job

TASTING HAS LITTLE TO DO WITH TASTE

THE SENSORY ANALYST rides a Harley. There are surely many things she enjoys about traveling by motorcycle, but the one Sue Langstaff mentions to me is the way the air, the great and odorous out-of-doors, is shoved into her nose. It’s a big, lasting passive sniff. [4] A few words on sniffing. Without it (or a Harley), you miss all but the most potent of smells going on around you. Only 5 to 10 percent of air inhaled while breathing normally reaches the olfactory epithelium, at the roof of the nasal cavity. Olfaction researchers in need of a controlled, consistently sized sniff use an olfactometer to deliver “odorant pulses.” The technique replaces the rather more vigorous “blast olfactometry” as well as the original olfactometer, which connected to a glass and aluminum box called the “camera inodorata.” (“The subject’s head was placed in the box,” wrote the inventor, alarmingly, in 1921.)

This is why dogs stick their heads out the car window. It’s not for the feeling of the wind in their hair. When you have a nose like a dog has, or Sue Langstaff, you take in the sights by smell. Here is California’s Highway 29 between Napa and St. Helena, through Langstaff’s nose: cut grass, diesel from the Wine Train locomotive, sulfur being sprayed on grapes, garlic from Bottega Ristorante, rotting vegetation from low tide on the Napa River, toasting oak from the Demptos cooperage, hydrogen sulfide from the Calistoga mineral baths, grilling meat and onions from Gott’s drive-in, alcohol evaporating off the open fermenters at Whitehall Lane Winery, dirt from a vineyard tiller, smoking meats at Mustards Grill, manure, hay.

Tasting—in the sense of “wine-tasting” and of what Sue Langstaff does when she evaluates a product—is mostly smelling. The exact verb would be flavoring , if that could be a verb in the same way tasting and smelling are. Flavor is a combination of taste (sensory input from the surface of the tongue) and smell, but mostly it’s the latter. Humans perceive five tastes—sweet, bitter, salty, sour, and umami (brothy)—and an almost infinite number of smells. Eighty to ninety percent of the sensory experience of eating is olfaction. Langstaff could throw away her tongue and still do a reasonable facsimile of her job.

Her job. It is a kind of sensory forensics. “People come to me and say, ‘My wine stinks. What happened?’” Langstaff can read the stink. Off-flavors—or “defects,” in the professional’s parlance—are clues to what went wrong. An olive oil with a flavor of straw or hay suggests a problem with desiccated olives. A beer with a “hospital” smell is an indication that the brewer may have used chlorinated water, even just to rinse the equipment. The wine flavors “leather” and “horse sweat” are tells for the spoilage yeast Brettanomyces .

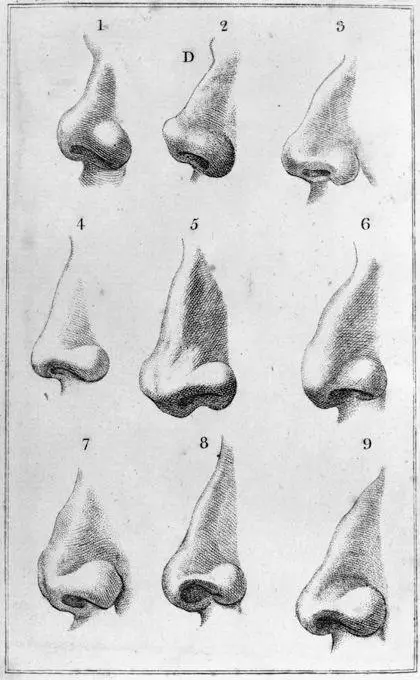

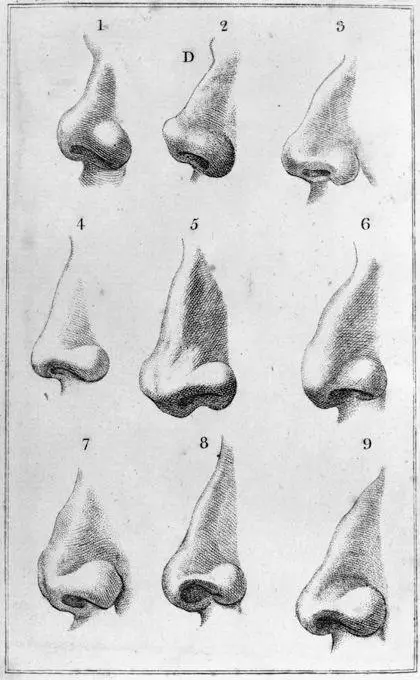

The nose is a fleshly gas chromatograph. As you chew food or hold wine in the warmth of your mouth, aromatic gases are set free. As you exhale, these “volatiles” waft up through the posterior nares—the internal nostrils [5] An Internet search on the medical term for nostrils produced this: “Save on Nasal Nares! Free 2-day Shipping with Amazon Prime.” They really are taking over the world.

at the back of the mouth—and connect with olfactory receptors in the upper reaches of the nasal cavity. (The technical name for this internal smelling is retronasal olfaction. The more familiar sniffing of aromas through the external nostrils is called orthonasal olfaction.) The information is passed on to the brain, which scans for a match. What sets a professional nose apart from an everyday nose is not so much its sensitivity to the many aromas in a food or drink, but the ability to tease them apart and identify them.

Читать дальше