1. THE STRATEGY MUST HAVE AN EXPLICIT REPRESENTATION OF THE DESIGNATED OUTCOME. If the strategy does not identify and get the specified outcome then it is useless.

The test phase of the TOTE, as discussed in Chapter II, requires that the organism compare a representation of where they are now with where they desire to be. For this an explicit representation of the outcome is essential. How many of you readers when you've tried to help someone make a decision or implement some new behavior, have asked questions like, "What do you want out of this interaction?" or "How will you know if you've (changed, made a good decision, etc.)?" or "Where are you trying to go with all of this?" and received answers like, "Well, I'd be happier," "I'd just feel differently," "Things would be better," or "Things wouldn't be the way they are now." None of these responses provide enough information from which to build an adequate strategy. It is no wonder that such persons have been unable to achieve their "goals."

When somebody simply says, "I would feel different," he has represented his desired outcome only in the kinesthetic channel and may not have any idea how things would look, sound or smell when change has taken place. Such a person doesn't have any way of devising operations utilizing these sensory modalities.

Choosing the sensory systems with which to represent the desired outcome is a crucial step in the design of any strategy. Sometimes a person may overspecify his outcome. A person, for instance, may construct a visual image of how he thinks his friends and family and associates should look and act in order for that individual to have secured his outcome. If the individual begins to carry out operations to make his friends, family and associates look and act that way, everybody involved may experience a great deal of discomfort and frustration — a so–called disappointment strategy. In some cases you will want to leave some aspects of the outcome unspecified until you have gathered more information. There are some aspects of particular outcomes that sometimes cannot or should not be decided ahead of time. In instances where this is the case, however, an explicit operation to get feedback and to gather information from which to build or modify a representation of the outcome should be included in the strategy. Implicit in this well–formedness condition, of course, is the requirement that the strategy secure the desired outcome it has represented.

2. ALL THREE MAJOR PRIMARY REPRESENTATIONAL SYSTEMS (V, A and K) MUST BE INVOLVED IN THE STRATEGY SEQUENCE. Each of our representational systems is capable of gathering and processing information that is not available to the others. We can perceive and organize things visually that we cannot do kinesthetically or auditorily. We can sense and process things kinesthetically that we cannot do visually and auditorily and so on. This condition will insure that the resources of each system and therefore of the organism are at least potentially available.

3. AFTER "N" MANY STEPS, MAKE SURE ONE OF THE MODIFIERS IS EXTERNAL. This means that after so many steps in the strategy the individual should tune one of his/her representational systems to the external environment. This is to insure that the person or organization is getting feedback from their external context so they will be able to detect what effect the progression of the strategy is having and so they will not become caught up in their own internal experience. "N" will be determined by the kind of task being performed. If it is important to the carrying out of a task (such as basketball or therapy) that you gear your responses on the basis of actions taking place in your external environment, then put in an external check often. If the task requires more internal processing (like writing down an incident from memory or solving a complicated math problem) your external checks can take place less often. If you are not certain how many external checks are required for a task, a good rule of thumb is is, "When in doubt, put one in."

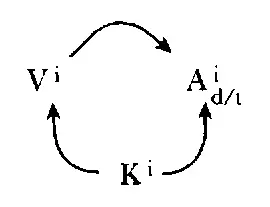

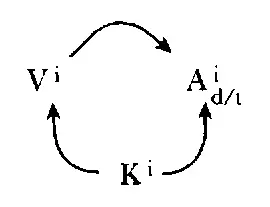

An alternative way of satisfying this requirement, especially in the context of tasks which require extensive internal processing, is the use of "counters." For example, suppose you are attempting to make a decision among several alternatives and your strategy involves a three point loop

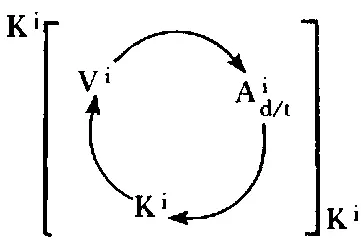

for each alternative. Specifically, you look at each alternative (V i), comment to yourself about it (A i d\t) and check to determine how you feel about it (K i). Your strategy allows you to cycle around the loop to edit the pictures (V i) based on the comments (A i d\t) and feelings (K i) you have in response to them in order to arrive at the best visual representation of that particular alternative. The danger here is that you could become trapped in the editing and stay in the loop too long. This well–formedness condition is designed to protect against such an occurrence. The condition of including an external check would require interrupting the internal processing each cycle around the loop to determine, for example, how much time has passed. Equally effective and more natural would be the maneuver of introducing a counter on the loop. There are two easy ways of accomplishing this: (1) In the V istep, you introduce a visual representation of a counter — that is, the first time through the numeral "1" is affixed visually to the starting image; each time the loop returns to that step (V i) the visual counter is incremented by 1, so that consecutive cycles are visually noted 1, 2, 3 … etc. Using this approach, the decision maker would determine, prior to beginning the process, the number of edits to allow for each alternative. When that numeral appears, the strategy kicks in the next alternative and resets the visual counter back to 1. (2) Introduce a K which is outside the loop

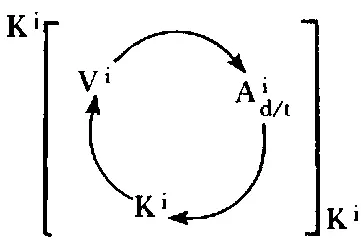

The K iis timed — that is, the decision maker determines prior to beginning the decision making how long to allow for constructing and editing each alternative. K iis set for that length of time. When that time period (kept kinesthetically) has elapsed the K ioutside the loop switches the decision maker into the next alternative to be considered.

4. THERE SHOULD BE NO TWO POINT LOOPS IN THE STRATEGY. A two point loop is a loop in the strategy where the individual cycles or spirals between two representational systems, the usual result being that the loop doesn't exit. The loop is kept from exiting due to an inadequate test or because the operate phase (which only involves one representation system) is too minimal to make any significant change in the value of the representation being tested for. Loops that do not exit can be established in strings of representations that display more than two points, of course, and these should be avoided as well. But the majority of spiraling cases occur in loops of only two points because they do not generally access enough information or behavior to form an effective TOTE. An example of a two point loop would be if, during some strategy, an individual triggers an internal voice that criticizes him in a high pitched, blaming tonality. The blaming voice, in turn, triggers negative visceral feelings. The voice then blames the individual for feeling bad, and this causes the person to feel even worse. The voice then becomes further agitated and blaming, and the loop spirals between auditory and kinesthetic:

The same sort of interaction can happen among people in a family, group or organization as well. Notice that a change in any of the modifiers in a particular representational step qualifies as a new distinction. A change from auditory internal (A i) to auditory external (A e) would have kept this sequence from becoming a two point loop. A change from tonal to digital, from remembered to constructed or from a polarity response to a meta response would each qualify as a legitimate difference in representational quality.

Читать дальше