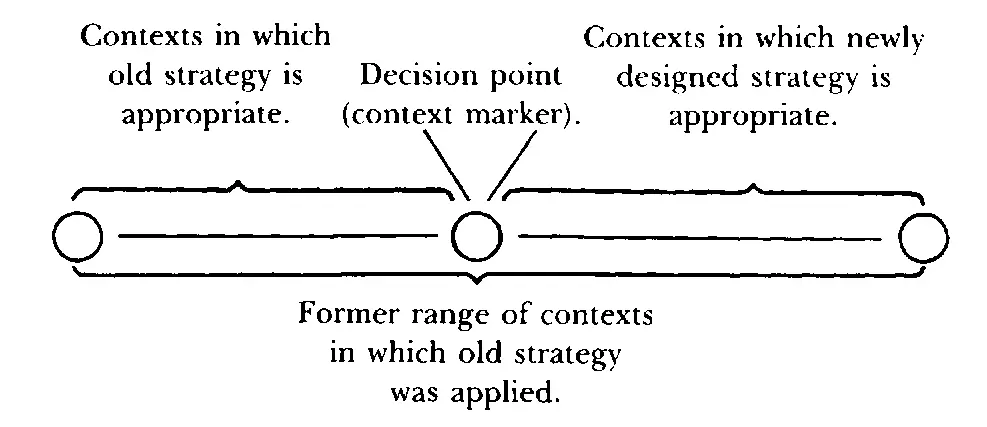

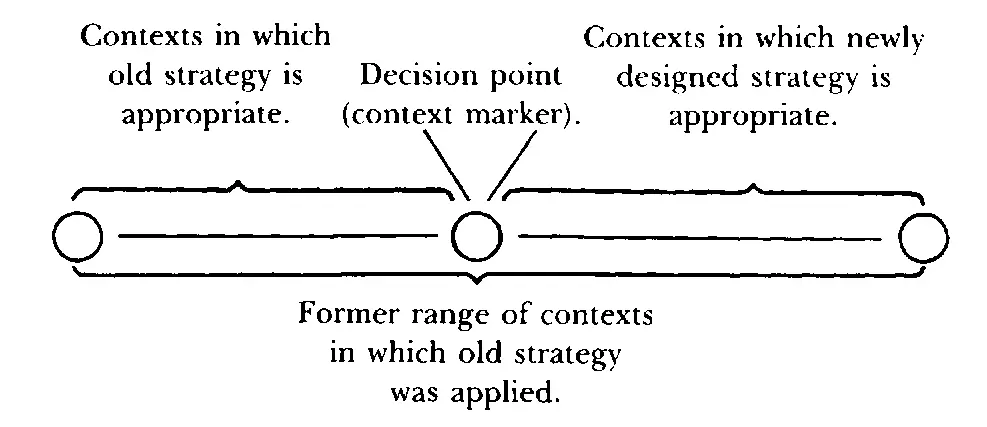

The representation that serves as a marker may take on any content. It could be a certain threshold of tonality, a particular word or class of words, a positive or negative kinesthetic sensation, or some visual image or distinction picked up in the environment. The purpose of the cue is, as shown below, to differentiate which context is appropriate for which strategy:

As a simple example of this, let's say you are working with a manager who has a strategy, when she sees one of her personnel making a mistake, of telling him (A e) that that isn't the way the job should be done, after which she shows him how to do it properly (V e). You design a new strategy which involves her pacing the employee posturally first, then explaining to the employee how she feels about the way the job should be done (K i→A e d), and finally walking him through what she feels to be the appropriate behavior for the task (K e). The old strategy is still appropriate, of course, for employees whose strategies are more visually oriented. The new strategy will be more effective with kinesthetically oriented personnel. The decision point, then, should involve a test that allows the manager to discriminate between individuals to determine which strategy would be more effective. A quick decision such as this can be readily based on a momentary observation of the body type, voice tonality, predicates and available accessing cues of the employee (V e/A e). The strategy that the manager chooses, then, is based on her observations of the employee.

Another example of this involves a situation similar to the phobia example presented earlier. A woman in her mid–thirties with whom one of the authors was working was having many problems with the man she lived with and was experiencing a lot of pain because she had a strong negative emotional response every time he raised his voice at her, even slightly. She would become overwhelmed by feelings of fear and would want to leave the room even though her partner was not at all angry or threatening. She didn't want or understand this response, and didn't know what to do about it.

Upon eliciting her strategy, the author discovered the following sequence for the woman's strategy: She would hear the rising volume of her partner's tonality (A e i) and access the sound of her father's voice (A i t), which was in many ways similar to that of her partner. This anchor would then access an image of her father (V r), who had beaten her severely as a child, approaching her with an angry facial expression. This would then reaccess all the feelings of fear and hopelessness that she had experienced as a child.

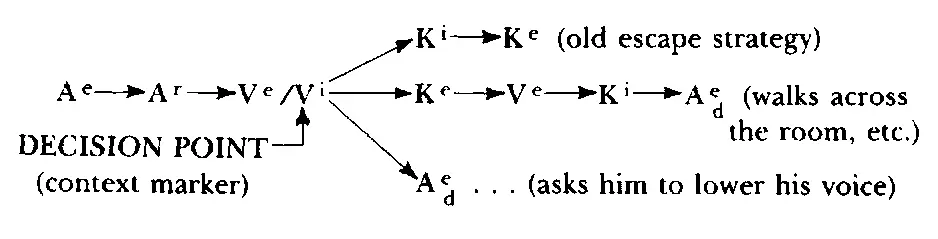

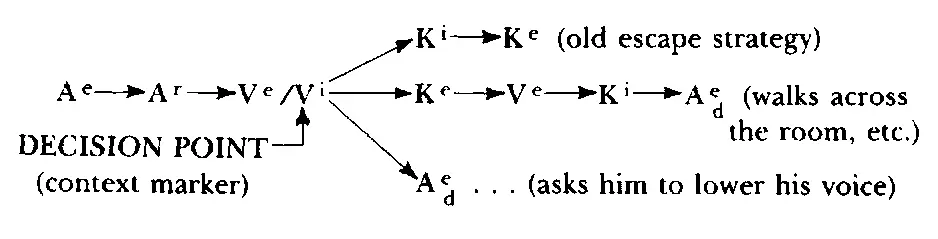

The author designed and installed a new strategy in which, as soon as she heard the volume of her partner's voice approaching that of her father, she would immediately look at him and compare the look on his face to the remembered threatening look of her father (V e/V r). If the two matched, then she could legitimately feel in danger and access her old response. If the two did not match (which was, of course, almost always the case) then she was to ask her partner to lower his voice (A e d) so it would be easier for her to communicate with him. If she wasn't sure, she was to walk across the room until she could look at him and feel that there was a safe distance between them (K e→V e→K i), and ask him to lower his voice (A e d). A certain pairing between tonality and facial expression, then, was used as a context marker or decision criterion to choose which operation or strategy to access. Another way to think about this is that certain combinations of tonality and facial expression are programmed as anchors for different responses. We can show the newly designed strategy as follows:

The purpose of artificial design is to create a strategy that will secure the designated outcome or outcomes in the most efficient and effective manner when there is no appropriate strategy immediately available. This requires that the strategy contain all of the necessary tests and operations needed to sequence the behavior and gather the information and feedback involved in obtaining the desired outcome.

One useful method of designing effective strategies is to find a person, group or organization (depending on which you are dealing with) that already has the ability to achieve the outcome you desire to attain, and to use their strategy as a model for your design task. If you want to be able to do well in physics, find someone who already has that ability and use his strategy as a model from which to design your own. If you want to be able to get outcomes in the fields of therapy, management or law, find the people who are already able to do this and use their strategies as a model. [24] We have been making plans for some time to organize a project in which the twelve people who are best able to achieve outcomes in each of the major divisions of the sciences and the arts will be modeled for their strategies. This would result in a battery of the most effective strategies for many fields or sectors of organized human behavior.

This way you will be assured that the strategy you are designing will be effective.

This method of design has many implications for the field of education. We have pointed out before that many teachers don't actually have a good strategy for the subject they are teaching. A creative writing teacher, for instance, may have a good strategy for reading and criticizing literature, but not for generating it. By finding the the strategies of a number of people who are good creative writers, the teacher could improve the quality of his course, beginning each term by teaching and installing, during the first few days of the class, the effective creative writing strategies. Once she has done this, the teacher would then proceed with the content of the course. This will increase the effectiveness of students' writing abilities. The same procedure will work for all subjects — if the strategy for incorporating and handling the material is taught first, the learning of the content will be more easily and effectively accomplished.

When consulting for educational institutions we have often organized a series of study groups for students set up in the following way. Students are covertly divided up on the basis of their ability to achieve outcomes in the particular subject in question, into fast, medium and slow students. Each study group is composed of two students from each division (two fast, two medium, and two slow). After we teach them about representational systems, pacing and accessing cues, the students elicit and swap strategies with one another for a number of subjects. Invariably, students who are slow in one task have a better strategy for some other task, and each of the students is able to offer a resource to the group. Because each benefits from the others a support network with mutual rapport tends to be built. The process of eliciting and swapping strategies is also fun. And this kind of grouping will keep students, especially of grammar school age, from being labeled and reinforced as "slow" or "stupid." In many of the places where we have set up such a program there have been dramatic improvements in the performances of the "slow" students within a matter of days.

One should be careful, of course, when designing strategies through modeling, that you don't get stuck or stagnated with one particular model for doing things. Challenging the old limitations and models and creating new ones is the basic means for improvement available to us as a species. The neurolinguistic programming model itself is continually changing, transforming and improving itself.

Читать дальше