Although thinkers have pondered the mystery of consciousness for thousands of years, the rise of AI adds a sudden urgency, in particular to the question of predicting which intelligent entities have subjective experiences. As we saw in chapter 3, the question of whether intelligent machines should be granted some form of rights depends crucially on whether they’re conscious and can suffer or feel joy. As we discussed in chapter 7, it becomes hopeless to formulate utilitarian ethics based on maximizing positive experiences without knowing which intelligent entities are capable of having them. As mentioned in chapter 5, some people might prefer their robots to be unconscious to avoid feeling slave-owner guilt. On the other hand, they may desire the opposite if they upload their minds to break free from biological limitations: after all, what’s the point of uploading yourself into a robot that talks and acts like you if it’s a mere unconscious zombie, by which I mean that being the uploaded you doesn’t feel like anything? Isn’t this equivalent to committing suicide from your subjective point of view, even though your friends may not realize that your subjective experience has died?

For the long-term cosmic future of life (chapter 6), understanding what’s conscious and what’s not becomes pivotal: if technology enables intelligent life to flourish throughout our Universe for billions of years, how can we be sure that this life is conscious and able to appreciate what’s happening? If not, then would it be, in the words of the famous physicist Erwin Schrödinger, “a play before empty benches, not existing for anybody, thus quite properly speaking not existing”?2 In other words, if we enable high-tech descendants that we mistakenly think are conscious, would this be the ultimate zombie apocalypse, transforming our grand cosmic endowment into nothing but an astronomical waste of space?

What Is Consciousness?

Many arguments about consciousness generate more heat than light because the antagonists are talking past each other, unaware that they’re using different definitions of the C-word. Just as with “life” and “intelligence,” there’s no undisputed correct definition of the word “consciousness.” Instead, there are many competing ones, including sentience, wakefulness, self-awareness, access to sensory input and ability to fuse information into a narrative.3 In our exploration of the future of intelligence, we want to take a maximally broad and inclusive view, not limited to the sorts of biological consciousness that exist so far. That’s why the definition I gave in chapter 1, which I’m sticking with throughout this book, is very broad:

consciousness = subjective experience

In other words, if it feels like something to be you right now, then you’re conscious. It’s this particular definition of consciousness that gets to the crux of all the AI-motivated questions in the previous section: Does it feel like something to be Prometheus, AlphaGo or a self-driving Tesla?

To appreciate how broad our consciousness definition is, note that it doesn’t mention behavior, perception, self-awareness, emotions or attention. So by this definition, you’re conscious also when you’re dreaming, even though you lack wakefulness or access to sensory input and (hopefully!) aren’t sleepwalking and doing things. Similarly, any system that experiences pain is conscious in this sense, even if it can’t move. Our definition leaves open the possibility that some future AI systems may be conscious too, even if they exist merely as software and aren’t connected to sensors or robotic bodies.

With this definition, it’s hard not to care about consciousness. As Yuval Noah Harari puts it in his book Homo Deus: 4 “If any scientist wants to argue that subjective experiences are irrelevant, their challenge is to explain why torture or rape are wrong without reference to any subjective experience.” Without such reference, it’s all just a bunch of elementary particles moving around according to the laws of physics—and what’s wrong with that?

What’s the Problem?

So what precisely is it that we don’t understand about consciousness? Few have thought harder about this question than David Chalmers, a famous Australian philosopher rarely seen without a playful smile and a black leather jacket—which my wife liked so much that she gave me a similar one for Christmas. He followed his heart into philosophy despite making the finals at the International Mathematics Olympiad—and despite the fact that his only B grade in college, shattering his otherwise straight As, was for an introductory philosophy course. Indeed, he seems utterly undeterred by put-downs or controversy, and I’ve been astonished by his ability to politely listen to uninformed and misguided criticism of his own work without even feeling the need to respond.

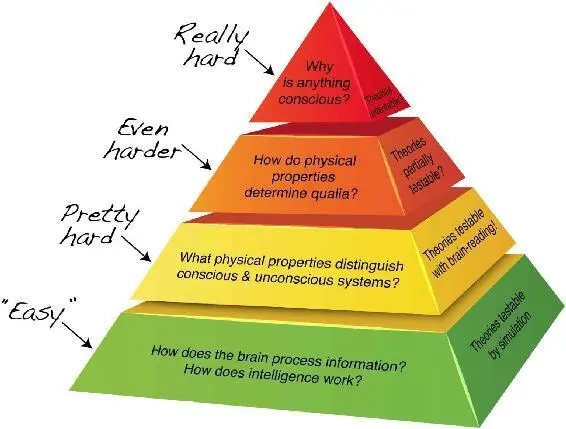

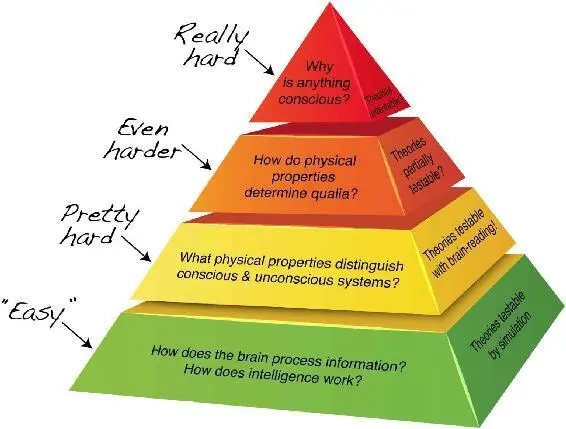

As David has emphasized, there are really two separate mysteries of the mind. First, there’s the mystery of how a brain processes information, which David calls the “easy” problems. For example, how does a brain attend to, interpret and respond to sensory input? How can it report on its internal state using language? Although these questions are actually extremely difficult, they’re by our definitions not mysteries of consciousness, but mysteries of intelligence: they ask how a brain remembers, computes and learns. Moreover, we saw in the first part of the book how AI researchers have started to make serious progress on solving many of these “easy problems” with machines—from playing Go to driving cars, analyzing images and processing natural language.

Then there’s the separate mystery of why you have a subjective experience, which David calls the hard problem. When you’re driving, you’re experiencing colors, sounds, emotions, and a feeling of self. But why are you experiencing anything at all? Does a self-driving car experience anything at all? If you’re racing against a self-driving car, you’re both inputting information from sensors, processing it and outputting motor commands. But subjectively experiencing driving is something logically separate—is it optional, and if so, what causes it?

I approach this hard problem of consciousness from a physics point of view. From my perspective, a conscious person is simply food, rearranged. So why is one arrangement conscious, but not the other? Moreover, physics teaches us that food is simply a large number of quarks and electrons, arranged in a certain way. So which particle arrangements are conscious and which aren’t? *1

Figure 8.1: Understanding the mind involves a hierarchy of problems. What David Chalmers calls the “easy” problems can be posed without mentioning subjective experience. The apparent fact that some but not all physical systems are conscious poses three separate questions. If we have a theory for answering the question that defines the “pretty hard problem,” then it can be experimentally tested. If it works, then we can build on it to tackle the tougher questions above.

What I like about this physics perspective is that it transforms the hard problem that we as humans have struggled with for millennia into a more focused version that’s easier to tackle with the methods of science. Instead of starting with a hard problem of why an arrangement of particles can feel conscious, let’s start with a hard fact that some arrangements of particles do feel conscious while others don’t. For example, you know that the particles that make up your brain are in a conscious arrangement right now, but not when you’re in deep dreamless sleep.

Читать дальше