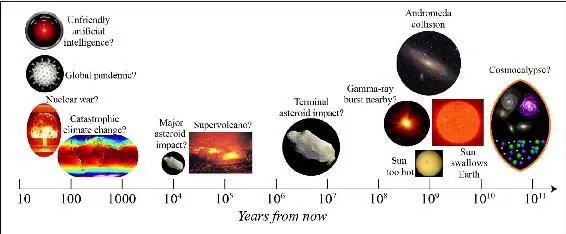

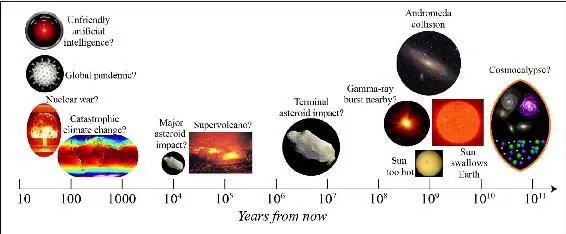

Figure 5.1: Examples of what could destroy life as we know it or permanently curtail its potential. Whereas our Universe itself will likely last for at least tens of billions of years, our Sun will scorch Earth in about a billion years and then swallow it unless we move it a safe distance, and our Galaxy will collide with its neighbor in about 3.5 billion years. Although we don’t know exactly when, we can predict with near certainty that long before this, asteroids will pummel us and supervolcanoes will cause yearlong sunless winters. We can use technology either to solve all these problems or to create new ones such as climate change, nuclear war, engineered pandemics or AI gone awry.

Self-Destruction

After contemplating problems that future technology might cause, it’s important to also consider problems that lack of that technology can cause. In this spirit, let us explore scenarios where superintelligence is never created because humanity eliminates itself by other means.

How might we accomplish that? The simplest strategy is “just wait.” Although we’ll see in the next chapter how we can solve such problems as asteroid impacts and boiling oceans, these solutions all require technology that we haven’t yet developed, so unless our technology advances far beyond its present level, Mother Nature will drive us extinct long before another billion years have passed. As the famous economist John Maynard Keynes said: “In the long run we are all dead.”

Unfortunately, there are also ways in which we might self-destruct much sooner, through collective stupidity. Why would our species commit collective suicide, also known as omnicide, if virtually nobody wants it? With our present level of intelligence and emotional maturity, we humans have a knack for miscalculations, misunderstandings and incompetence, and as a result, our history is full of accidents, wars and other calamities that, in hindsight, essentially nobody wanted. Economists and mathematicians have developed elegant game-theory explanations for how people can be incentivized to actions that ultimately cause a catastrophic outcome for everyone.6

Nuclear War: A Case Study in Human Recklessness

You might think that the greater the stakes, the more careful we’d be, but a closer examination of the greatest risk that our current technology permits, namely a global thermonuclear war, isn’t reassuring. We’ve had to rely on luck to weather an embarrassingly long list of near misses caused by all sorts of things: computer malfunction, power failure, faulty intelligence, navigation error, bomber crash, satellite explosion and so on.7 In fact, if it weren’t for heroic acts of certain individuals—for example, Vasili Arkhipov and Stanislav Petrov—we might already have had a global nuclear war. Given our track record, I think it’s highly unlikely that the annual probability of accidental nuclear war is as low as one in a thousand if we keep up our present behavior, in which case the probability that we’ll have one within 10,000 years exceeds 1− 0 . 999 10000≈ 99 . 995%.

To fully appreciate our human recklessness, we must realize that we started the nuclear gamble even before carefully studying the risks. First, radiation risks had been underestimated, and over $2 billion in compensation has been paid out to victims of radiation exposure from uranium handling and nuclear tests in the United States alone.8

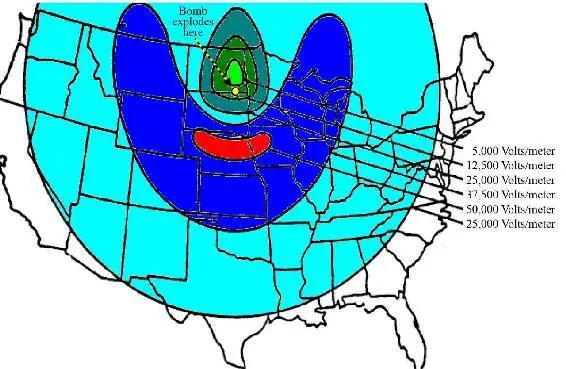

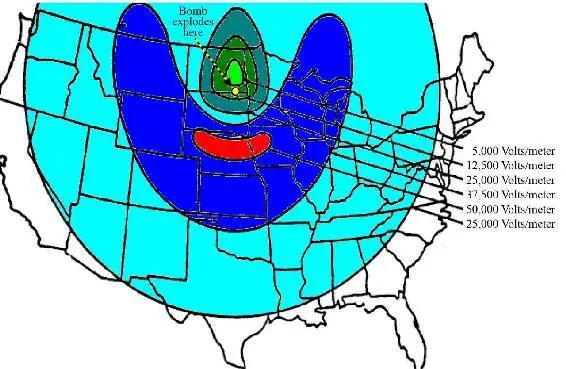

Second, it was eventually discovered that hydrogen bombs deliberately detonated hundreds of kilometers above Earth would create a powerful electromagnetic pulse (EMP) that might disable the electric grid and electronic devices over vast areas (figure 5.2), leaving infrastructure paralyzed, roads clogged with disabled vehicles and conditions for nuclear-aftermath survival less than ideal. For example, the U.S. EMP Commission reported that “the water infrastructure is a vast machine, powered partly by gravity but mostly by electricity,” and that denial of water can cause death in three to four days.9

Figure 5.2: A single hydrogen bomb explosion 400 km above Earth can cause a powerful electromagnetic pulse that can cripple electricity-using technology over a vast area. By shifting the detonation point southeast, the banana-shaped zone exceeding 37,500 volts per meter could cover most of the U.S. East Coast. Reprinted from U.S. Army Report AD-A278230 (unclassified) with colors added.

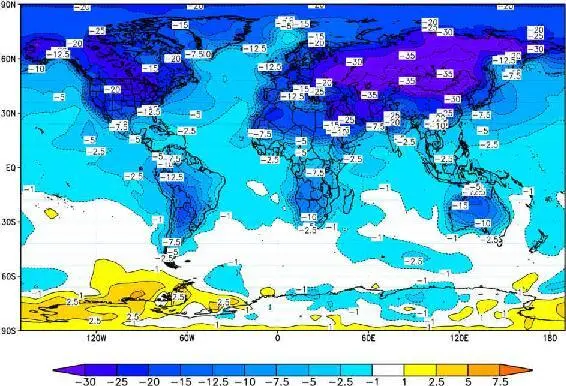

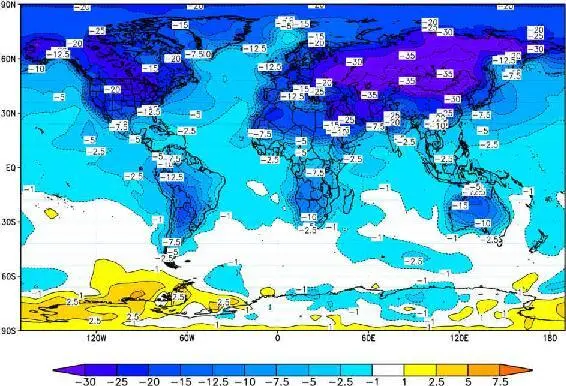

Third, the potential of nuclear winter wasn’t realized until four decades in, after we’d deployed 63,000 hydrogen bombs—oops! Regardless of whose cities burned, massive amounts of smoke reaching the upper troposphere might spread around the globe, blocking out enough sunlight to transform summers into winters, much like when an asteroid or supervolcano caused a mass extinction in the past. When the alarm was sounded by both U.S. and Soviet scientists in the 1980s, this contributed to the decision of Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev to start slashing stockpiles.10 Unfortunately, more accurate calculations have painted an even gloomier picture: figure 5.3 shows cooling by about 20° Celsius (36° Fahrenheit) in much of the core farming regions of the United States, Europe, Russia and China (and by 35°C in some parts of Russia) for the first two summers, and about half that even a full decade later. *4What does that mean in plain English? One doesn’t need much farming experience to conclude that near-freezing summer temperatures for years would eliminate most of our food production. It’s hard to predict exactly what would happen after thousands of Earth’s largest cities are reduced to rubble and global infrastructure collapses, but whatever small fraction of all humans don’t succumb to starvation, hypothermia or disease would need to cope with roving armed gangs desperate for food.

Figure 5.3: Average cooling (in °C) during the first two summers after a full-scale nuclear war between the United States and Russia. Reproduced with permission from Alan Robock.11

I’ve gone into such detail on global nuclear war to drive home the crucial point that no reasonable world leader would want it, yet it might nonetheless happen by accident. This means that we can’t trust our fellow humans never to commit omnicide: nobody wanting it isn’t necessarily enough to prevent it.

Doomsday Devices

So could we humans actually pull off omnicide? Even if a global nuclear war may kill off 90% of all humans, most scientists guess that it wouldn’t kill 100% and therefore wouldn’t drive us extinct. On the other hand, the story of nuclear radiation, nuclear EMP and nuclear winter all demonstrate that the greatest hazards may be ones we haven’t even thought of yet. It’s incredibly difficult to foresee all aspects of the aftermath, and how nuclear winter, infrastructure collapse, elevated mutation levels and desperate armed hordes might interact with other problems such as new pandemics, ecosystem collapse and effects we haven’t yet imagined. My personal assessment is therefore that although the probability of a nuclear war tomorrow triggering human extinction isn’t large, we can’t confidently conclude that it’s zero either.

Omnicide odds increase if we upgrade today’s nuclear weapons into a deliberate doomsday device. Introduced by RAND strategist Herman Kahn in 1960 and popularized in Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove, a doomsday device takes the paradigm of mutually assured destruction to its ultimate conclusion. It’s the perfect deterrent: a machine that automatically retaliates against any enemy attack by killing all of humanity.

Читать дальше