Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

From observations of neighborhoods that succeed in being well-defined, both physically and in the minds of the townspeople, we have learned that the single most important feature of a neighborhood’s boundary is restricted access into the neighborhood: neighborhoods that are successfully defined have definite and relatively few paths and roads leading into them.

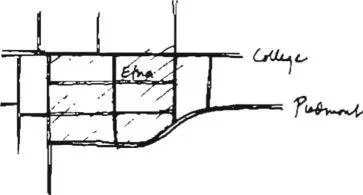

For example, here is a map of the Etna Street neighborhood in Berkeley.

Our neighborhood , compared with a typical part of a grid system.

There are only seven roads into this neighborhood, compared with the fourteen which there would be in a typical part of the street grid. The other roads all dead end in T junctions immediately at the edge of the neighborhood. Thus, while the Etna Street neighborhood is not literally walled off from the community, access into it is subtly restricted. The result is that people do not come into the neighborhood by car unless they have

15 NEIGHBORHOOD BOUNDARY

business there 5 and when people are in the neighborhood, they recognize that they are in a distinct part of town. Of course, the neighborhood was not “created” deliberately. It was an area of Berkeley which has become an identifiable neighborhood because of this accident in the street system.

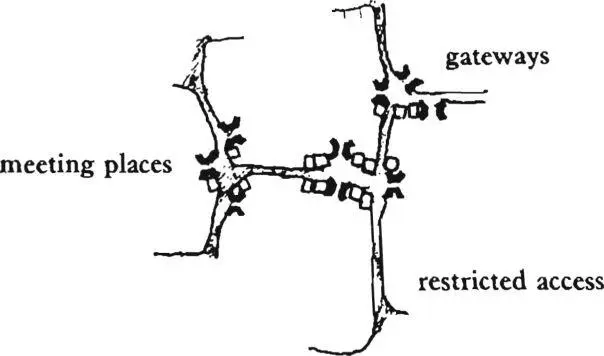

An extreme example of this principle is the Fuggerei in Augsburg, illustrated in identifiable neighborhood(14). The Fuggerei is entirely bounded by the backs of buildings and walls, and the paths into it are narrow, marked by gateways.

Indeed, if access is restricted, this means, by definition , that those few points where access is possible, will come to have special importance. In one way or another, subtly, or more obviously, they will be gateways, which mark the passage into the neighborhood. We discuss this more fully in main gateways(53). But the fact is that every successful neighborhood is identifiable because it has some kind of gateways which mark its boundaries: the boundary comes alive in peoples’ minds because they recognize the gateways.

In case the idea of gateways seems too closed, we remark at once that the boundary zone—and especially those parts of it around the gateways—must also form a kind of public meeting ground, where neighborhoods come together. If each neighborhood is a self-contained entity, then the community of 7000 which the neighborhoods belong to will not control any of the land internal to the neighborhoods. But it will control all of the land between the neighborhoods—the boundary land—because this boundary land is just where functions common to all 7000 people must find space. In this sense the boundaries not only serve to protect individual neighborhoods, but simultaneously function to unite them in their larger processes.

Therefore:

Encourage the formation of a boundary around each neighborhood, to separate it from the next door neighborhoods. Form this boundary by closing down streets and limiting access to the neighborhood—cut the normal number of streets at least in half. Place gateways at those points where the restricted access paths cross the boundary; and

TOWNS

make the boundary zone wide enough to contain meeting places for the common functions shared by several neighborhoods.

The easiest way of all to form a boundary around a neighborhood is by turning buildings inward, and by cutting off the paths which cross the boundary, except for one or two at special points which become gateways—main gateways (53); the public land of the boundary may include a park, collector roads, small parking lots, and work communities—anything which forms a natural edge—parallel roads (23), work community (41), QUIET BACKS (59), ACCESSIBLE GREEN (60), SHIELDED PARKING

(97), small parking lots (103). As for the meeting places in the boundary, they can be any of those neighborhood functions which invite gathering: a park, a shared garage, an outdoor room, a shopping street, a playground—shopping street (32), pools

AND STREAMS (64), PUBLIC OUTDOOR ROOM (69), GRAVE SITES (70), LOCAL SPORTS (72), ADVENTURE PLAYGROUND (73). . . .

90

connect communities to one another by encouraging the growth of the following networks:

16. WEB OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

17. RINGROADS

18. NETWORK OF LEARNING

19. WEB OF SHOPPING

20. MINI-BUSES

16 WEB OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION*

. . . the city, as defined by city country pincers(3), spreads out in ribbon fashion, throughout the countryside, and is broken into local transport areas(ii). To connect the transport areas, and to maintain the flow of people and goods along the fingers of the cities, it is now necessary to create a web of public tranportation.

The system of public transportation—the entire web of airplanes, helicopters, hovercraft, trains, boats, ferries, buses, taxis, mini-trains, carts, ski-lifts, moving sidewalks —can only work if all the parts are well connected. But they usually aren’t, because the different agencies in charge of various forms of public transportation have no incentives to connect to one another.

Here, in brief, is the general public transportation problem. A city contains a great number of places, distributed rather evenly across a two-dimensional sheet. The trips people want to make are typically between two points at random in this sheet. No one linear system (like a train system), can give direct connections between the vast possible number of point pairs in the city.

It is therefore only possible for systems of public transportation to work, if there are rich connections between a great variety of different systems. But these connections are not workable, unless they are genuine fast, short, connections. The waiting time for a connection must be short. And the walking distance between the two connecting systems must be very short.

This much is obvious; and everyone who has thought about public transportation recognizes its importance. However, obvious though it is, it is extremely hard to implement.

I 6 WEB OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION

There are two practical difficulties, both of which stem from the fact that different kinds of public transportation are usually in the hands of different agencies who are reluctant to cooperate. They are reluctant to cooperate, partly because they are actually in competition, and partly just because cooperation makes life harder for them.

This is particularly true along commuting corridors. Trains, buses, mini-buses, rapid transit, ferries, and maybe even planes and helicopters compete for the same passenger market along these corridors. When each mode is operated by an independent agency there is no particular incentive to provide feeder services to the more inflexible modes. Many services are even reluctant to provide good feeder connections to rapid transit, trains, and ferries, because their commuter lines are their most lucrative lines. Similarly, in many cities of the developing world, minibuses and collectivos provide public transportation along the main commuting corridors, pulling passengers away from buses. This leaves the mainlines served by small vehicles, while almost empty buses reach the peripheral lines, usually because the public bus company is required to serve these areas, even at a loss.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.