Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

neighborhood witJi heavy traffic 16,000 vehicles/day 1900 vehicles/peak hour 35-40 mph One-way

Residents speaking on “neighboring and visiting”

It's not a friendly street—no one offers help.

People are afraid to go into the street because of the traffic.

Residents speaking on “home territory”

It is impersonal and public.

Noise from the street intrudes into my home.

How shall we define a major road? The Appleyard-Lintell study found that with more than 200 cars per hour, the quality of the neighborhood begins to deteriorate. On the streets with 550 cars per hour people visit their neighbors less and never gather in the street to meet and talk. Research by Colin Buchanan indicates that major roads become a barrier to free pedestrian movement when “most people (more than 50%) . . . have to adapt their movement to give way to vehicles. 5’ This is based on “an average delay to all crossing pedestrians of 2 seconds ... as a very rough guide to the borderline between acceptable and unacceptable conditions,” which happens when the traffic reaches some 150 to 250 cars per hour. (Colin D. Buchanan, Traffic in Towns , London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963, p. 204.) Thus any street with greater than 200 cars per hour, at any time, will probably seem “major,” and start to destroy the neighborhood identity.

A final note on implementation. Several months ago the City of Berkeley began a transportation survey with the idea of deciding the location of all future major arteries within the city. Citizens were asked to make statements about areas which they wanted to protect from heavy traffic. This simple request has caused widespread grass roots political organizing to take place: at the time of this writing more than 30 small neighborhoods have identified themselves, simply in order to make sure that they succeed in keeping heavy traffic out. In short, the issue of traffic is so fundamental to the fact of neighborhoods, that neighborhoods emerge, and crystallize, as soon as people are asked to decide where they want nearby traffic to be. Perhaps this is a universal way of implementing this pattern in existing cities.

Therefore:

Help people to define the neighborhoods they live in, not more than 300 yards across, with no more than 400 or 500 inhabitants. In existing cities, encourage local groups to organize themselves to form such neighborhoods. Give the neighborhoods some degree of autonomy as far as taxes and land controls are concerned. Keep major roads outside these neighborhoods.

max. population of 500

|

| max diameter of 300 yards |

Mark the neighborhood, above all, by gateways wherever main paths enter it— main gateways(53)—and by modest boundaries of non-residential land between the neighborhoods— neighborhood boundary(15). Keep major roads within these boundaries —parallel roads(23) ; give the neighborhood a visible center, perhaps a common or a green— accessible green (6o)—or a small public square(61); and arrange houses and workshops within the neighborhood in clusters of about a dozen at a time— HOUSE CLUSTER(37), WORK COMMUNITY(41). . . .

A PATTERN LANGUAGE

want to lay out a green according to this pattern, you must not only follow the instructions which describe the pattern itself, but must also try to embed the green within an identifiable neighborhood or in some subculture boundary, and in a way that helps to form quiet backs3 and then you must work to complete the green by building in some positive outdoor space, tree places, and a garden wall.

In short, no pattern is an isolated entity. Each pattern can exist in the world, only to the extent that is supported by other patterns: the larger patterns in which it is embedded, the patterns of the same size that surround it, and the smaller patterns which are embedded in it.

This is a fundamental view of the world. It says that when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole 3 and the thing which you make takes its place in the web of nature, as you make it.

Now we explain the nature of the relation between problems and solutions, within the individual patterns.

Each solution is stated in such a way that it gives the essential field of relationships needed to solve the problem, but in a very general and abstract way—so that you can solve the problem for yourself, in your own way, by adapting it to your preferences, and the local conditions at the place where you are making it.

For this reason, we have tried to write each solution in a way which imposes nothing on you. It contains only those essentials which cannot be avoided if you really

| 15 NEIGHBORHOOD BOUNDARY* |

|---|

|

86

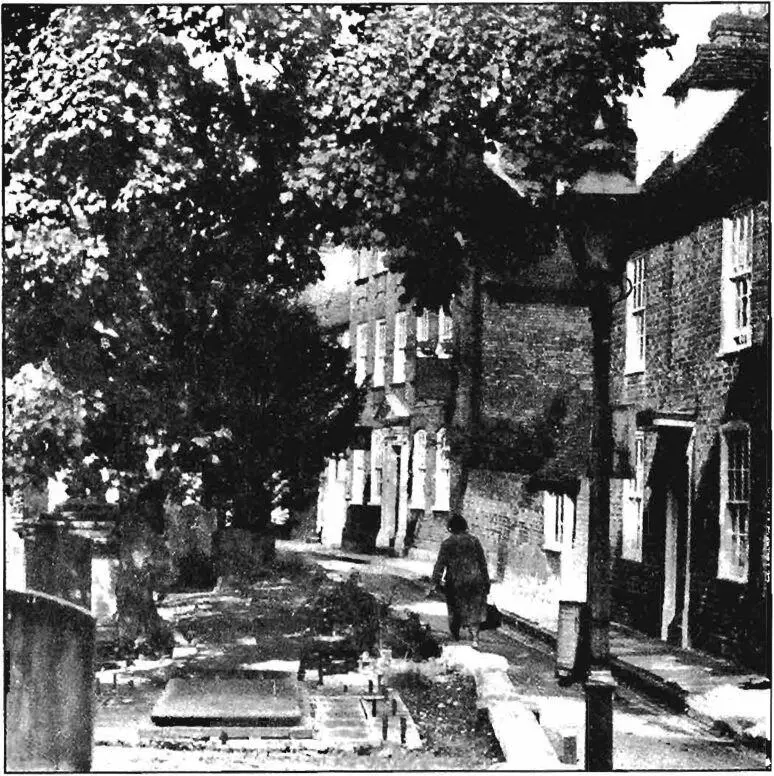

. . . the physical boundary needed to protect subcultures from one another, and to allow their ways of life to be unique and idiosyncratic, is guaranteed, for a community of7000 (12), by the pattern subculture boundary(13). But a second, smaller kind of boundary is needed to create the smaller identifiable NEIGHBORHOOD (iq).

The strength of the boundary is essential to a neighborhood. If the boundary is too weak the neighborhood will not be able to maintain its own identifiable character.

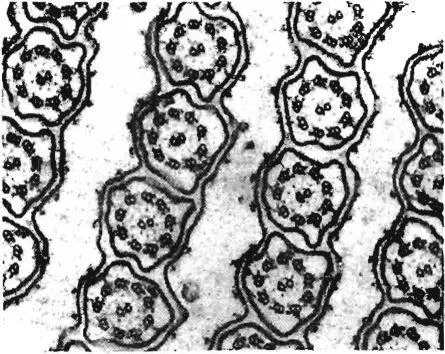

The cell wall of an organic ceil is, in most cases, as large as, or larger, than the cell interior. It is not a surface which divides inside from outside, but a coherent entity in its own right, which preserves the functional integrity of the cell and also provides for a multitude of transactions between the cell interior and the ambient fluids.

|

| Cell with cell wall: The cell wall is a place in its own right. |

We have already argued, in subculture boundary(13), that a human group, with a specific life style, needs a boundary around it to protect its idiosyncrasies from encroachment and dilution by surrounding ways of life. This subculture boundary,

then, functions just like a cell wall—it protects the subculture and creates space for its transactions with surrounding functions.

The argument applies as strongly to an individual neighborhood, which is a subculture in microcosm.

However, where the subculture boundaries require wide swaths of land and commercial and industrial activity, the neighborhood boundaries can be much more modest. Indeed it is not possible for a neighborhood of 500 or more to bound itself with shops and streets and community facilities; there simply aren’t enough to go around. Of course, the few neighborhood shops there are— the street cafe(88), the corner crocery(89)—will help to form the edge of the neighborhood, but by and large the boundary of neighborhoods will have to come from a completely different morphological principle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.