Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

will not be able to solve their own environmental problems. The arbitrary lines of states and countries, which often cut across natural regional boundaries, make it all but impossible for people to solve regional problems in a direct and humanly efficient way.

An extensive and detailed analysis of this idea has been given by the French economist Gravier, who has proposed, in a series of books and papers, the concept of a Europe of the Regions, a Europe decentralized and reorganized around regions which cross present national and subnational boundaries. (For example, the Basel-Strasbourg Region includes parts of France, Germany, and Switzerland; the Liverpool Region includes parts of England and parts of Wales). See Jean-Frangois Gravier, “L’Europe des regions,” in 1965 Internationale Regio Planertagung, Schriften der Regio 3, Regio, Basel, 1965, pp. 211-22; and in the same volume see also Emrys Jones, “The Conflict of City Regions and Administrative Units in Britain,” pp. 223—35.

4. Finally, unless the present-day great nations have their power greatly decentralized, the beautiful and differentiated languages, cultures, customs, and ways of life of the earth’s people, vital to the health of the planet, will vanish. In short, we believe that independent regions are the natural receptacles for language, culture, customs, economy, and laws and that each region should be separate and independent enough to maintain the strength and vigor of its culture.

The fact that human cultures within a city can only flourish when they are at least partly separated from neighboring cultures is discussed in great detail in mosaic of subcultures (8). We are suggesting here that the same argument also applies to regions —that the regions of the earth must also keep their distance and their dignity in order to survive as cultures.

In the best of medieval times, the cities performed this function. They provided permanent and intense spheres of cultural influence, variety, and economic exchange; they were great communes, whose citizens were co-members, each with some say in the city’s destiny. We believe that the independent region can become the modern polis—the new commune—that human entity which provides the sphere of culture, language, laws, services, economic exchange, variety, which the old walled city or the polis provided for its members.

This simple statement, if taken seriously, will make a revolution in the shape of buildings. At present, people take for granted that it is possible to use indoor space which is lit by artificial light; and buildings therefore take on all kinds of shapes and depths.

If we treat the presence of natural light as an essential —not optional—feature of indoor space, then no building could ever be more than 20—25 feet deep, since no point in a building which is more than about I 2 or 15 feet from a window, can get good natural light.

Later on, in light on two sides (159), we shall argue, even more sharply, that every room where people can feel comfortable must have not merely one window, but two, on different sides. This adds even further structure to the building shape: it requires not only that the building be no more than 25 feet deep, but also that its outer walls are continually broken up by corners and reentrant corners to give every room two outside walls.

The present pattern, which requires that buildings be made up of long and narrow wings, lays the groundwork for the later pattern. Unless the building is first conceived as being made of long, thin wings, there is no possible way of introducing light on two sides (159), in its complete form, later in the process. Therefore, we first build up the argument for this pattern, based on the human requirements for natural light, and later, in light on two sides (159), we shall be concerned with the organization of windows within a particular room.

There are two reasons for believing that people must have buildings lit essentially by sun.

First, all over the world, people are rebelling against windowless buildings; people complain when they have to work in places without daylight. By analyzing words they use, Rapoport has shown that people are in a more positive frame of mind in rooms with windows than in rooms without windows. (Amos Rapoport, “Some Consumer Comments on a Designed Environment,” Arena, January, 1967, pp. 176-78.) Edward Hall tells the story of a man who worked in a windowless office for some time, all the time saying that it was “just fine, just fine,” and then abruptly quit. Hall says, “The issue was so deep, and so serious, that this man could not even bear to discuss it, since just discussing it would have opened the floodgates.”

107 WINGS OF LIGHT

Second, there is a growing body of evidence which suggests that man actually needs daylight, since the cycle of daylight somehow plays a vital role in the maintenance of the body’s circadian rhythms, and that the change of light during the day, though apparently variable, is in this sense a fundamental constant by which the human body maintains its relationship to the environment. (See, for instance, R. G. Hopkinson, Architectural Physics: Lighting , Department of Scientific & Industrial Research, Building Research Station, HMSO, London, 1963, pp. 116-17.) If this is true, then too much artificial light actually creates a rift between a person and his surroundings and upsets the human physiology.

Many people will agree with these arguments. Indeed, the arguments merely express precisely what all of us know already: that it is much more pleasant to be in a building lit by daylight than in one which is not. But the trouble is that many of the buildings which are built without daylight are built that way because of density. They are built compact, in the belief that it is necessary to sacrifice daylight in order to reach high densities.

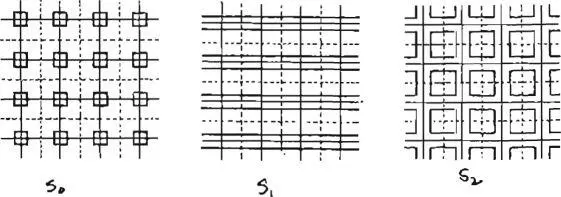

Lionel March and Leslie Martin have made a major contribution to this discussion. (Leslie Martin and Lionel March, Land Use and Built Form, Cambridge Research, Cambridge University, April 1966.) Using the ratio of built floor area to total site area as a measure of density and the semi-depth of the building as a measure of daylight conditions, they have compared three different arrangements of building and open space, which they call So, Si, and S2.

|

| Three building types. |

Of the three arrangements, S2, in which buildings surround the outdoors with thin wings, gives the best daylight conditions

BUILDINGS

for a fixed density. It also gives the highest density for a fixed level of daylight.

There is another criticism that is often leveled against this pattern. Since it tends to create buildings which are narrow and rambling, it increases the perimeter of buildings and therefore raises building cost substantially. How big is the difference? The following figures are taken from a cost analysis of standard office buildings used by Skidmore Owings and Merrill, in the program BOP (Building Optimization). These figures illustrate costs for a typical floor of an office building and are based on costs of 2 1 dollars per square foot for the structure, floors, finishes, mechanical, and so on, not including exterior wall, and a cost of 110 dollars per running foot for the perimeter wall. (Costs arc for 1969.)

| Area (Sq. Ft.) | Shape | Perimeter Cost (S) | Perimeter Cost Per Sq. Ft. (S) | Total Cost Per Sq. Ft. (S) |

| 15,000 | 120 x 125 | $54,000 | 3- 6 | 24.6 |

| 15>°°° | 100 x 150 | 55,000 | 3-7 | 24.7 |

| 15,000 | 75 x 200 | 60,500 | 4.0 | 25.0 |

| 15,000 | 60 x 250 | 68,000 | 4-5 | 25-5 |

| 15,000 | 50 x 300 | 77,000 | 26.1 | |

| The extra ferimeter adds little to building costs. |

We see then, that at least in this one case, the cost of the extra perimeter adds very little to the cost of the building. The narrowest building costs only 6 per cent more than the squarest. We believe this case is fairly typical and that the cost savings to be achieved by square and compact building forms have been greatly exaggerated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.