Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

So far, our discussion of proximity has been based on horizontal distances. How do stairs enter in? What part does vertical distance play in the experience of proximity? Or, to put it more precisely, what is the horizontal equivalent of one flight of stairs? Suppose two departments need to be within too feet of one another, according to the proximity graph—and suppose that they are for some reason on different stories, one floor apart. How much of the ioo feet does the stair eat up: with the stair between them, how far apart can they be horizontally?

We do not know the exact answer to this question. However, we do have some indirect evidence from an unpublished study by Marina Estabrook and Robert Sommer. As we shall see, this study shows that stairs play a much greater role, and eat up much more “distance” than you might imagine.

Estabrook and Sommer studied the formation of acquaintances in a three-story university building, where several different departments were housed. They asked people to name all the people they knew in departments other than their own. Their results were as follows:

Percent of people known: When departments are:

12.2 on same floor

8.9 one floor apart

2.2 two floors apart

People knew 12.2 per cent of the people from other departments on the same floor as their own, 8.9 per cent of the people from other departments one floor apart from their own floor, and only 2.2 per cent of the people from other departments two floors apart from their own. In short, by the time departments are separated by two floors or more, there is virtually no informal contact between the departments.

Unfortunately, our own study of proximity was done before we knew about these findings by Estabrook and Sommer; so we have not yet been able to define the relation between the two kinds of distance. It is clear, though, that one stair must be equivalent to a rather considerable horizontal distance; and that two flights of stairs have almost three times the effect of a single stair. On the basis of this evidence, we conjecture that one stair is equal to about TOO horizontal feet in its effect on interaction

82 OFFICE CONNECTIONS

and feelings of distance; and that two flights of stairs are equal to about 300 horizontal feet.

Therefore:

To establish distances between departments, calculate the number of trips per day made between each two departments; get the “nuisance distance” from the graph above; then make sure that the physical distance between the two departments is less than the nuisance distance . Reckon one flight of stairs as about 100 feet, and two flights of stairs as about 300 feet.

mmw/o

two floors maximum

rana met imiiii iinrni

less than nuisance distance

•J*

Keep the buildings which house the departments in line with the four-story limit (21), and get their shape from building complex (95). Give every working group on upper storys its own stair to connect it directly to the public world—pedestrian street (100),open stairs ( 158) ; if there are internal corridors between groups, make them large enough to function as streets—building thoroughfare (ioi); and identify each workgroup clearly, and give it a well-marked entrance, so that people easily find their way from one to another—family of entrances (102). . . .

411

83 MASTER AND APPRENTICES*

41 2

. . . the network of learning (18) in the community relies on the fact that learning is decentralized, and part and parcel of every activity—not just a classroom thing. In order to realize this pattern, it is essential that the individual workgroups, throughout industry, offices, workshops, and work communities, are all set up to make the learning process possible. This pattern, which shows the arrangement needed, therefore helps greatly to form self-governing workshops and offices (8o) as well as the network of learning (18).

* * *

The fundamental learning situation is one in which a person learns by helping someone who really knows what he is doing.

It is the simplest way of acquiring knowledge, and it is powerfully effective. By comparison, learning from lectures and books is dry as dust. But this situation has all but disappeared from modern society. The schools and universities have taken over and abstracted many ways of learning which in earlier times were always closely related to the real work of professionals, tradesmen, artisans, independent scholars. In the twelfth century, for instance, young people learned by working beside masters—helping them, making contact directly with every corner of society. When a young person found himself able to contribute to a field of knowledge, or a trade—he would prepare a master “piece”; and with the consent of the masters, become a fellow in the guild.

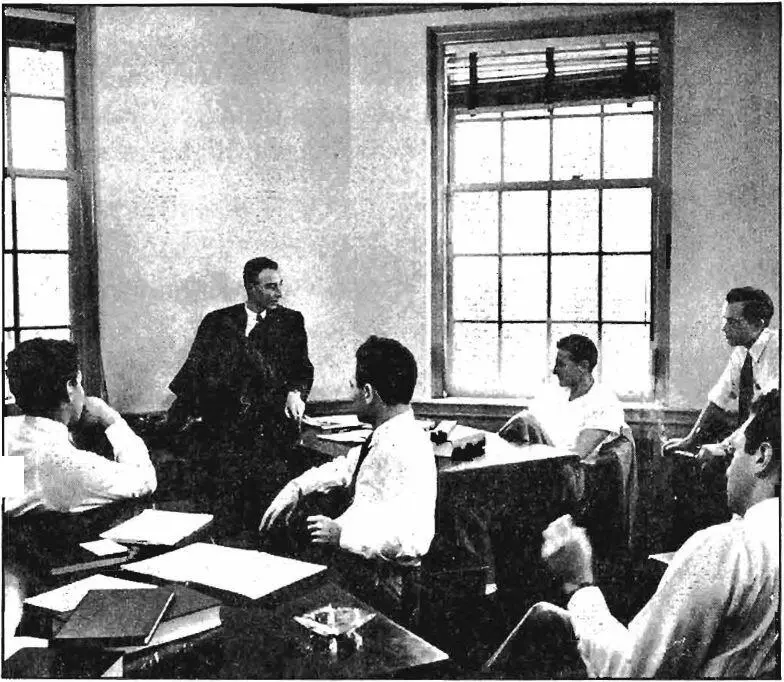

An experiment by Alexander and Goldberg has shown that a class in which one person teaches a small group of others is most likely to be successful in those cases where the “students” are actually helping the “teacher” to do something or solve some problem, which he is working on anyway—not when a subject of abstract or general interest is being taught. (Report to the Muscatine Committee, on experimental course F.D. 10X, Department of Architecture, University of California, 1966.)

If this is generally true—in short, if students can learn best when they are acting as apprentices, and helping to do something

TOWNS

interesting—it follows that our schools and universities and offices and industries must provide physical settings which make this master-apprentice relation possible and natural: physical settings where communal work is centered on the master’s efforts and where half a dozen apprentices—not more—have workspace closely connected to the communal work of the studio.

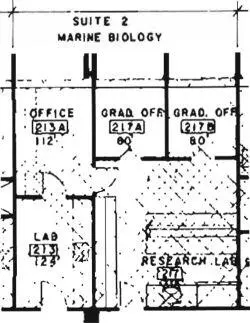

We know of an example of this pattern, in the Molecular Biology building of the University of Oregon. The floors of the building are made up of laboratories, each one under the direction of a professor of biology, each with two or three small rooms opening directly off the lab for graduate students working under the professor’s direction.

|

| Master-affrentice relationshif for a biology laboratory. |

We believe that variations of this pattern are possible in many different work organizations, as well as the schools. The practice of law, architecture, medicine, the building trades, social services, engineering—each discipline has the potential to set up its ways of learning, and therefore the environments in which its practitioners work, along these lines.

There fore:

Arrange the work in every workgroup, industry, and office, in such a way that work and learning go forward hand in hand. Treat every piece of work as an opportunity for learning. To this end, organize work around a tradition of masters and apprentices: and support this form of

83 MASTER AND APPRENTICES

social organization with a division of the workspace into spatial clusters—one for each master and his apprentices— where they can work and meet together.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.