Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At one extreme there are ideas like Habraken’s high density “support” system, where families buy pads on publicly owned superstructures and gradually develop their own homes. And at the other extreme there are the rural communes, where people have forsaken the city to create their own homes in the country. Even modified forms of rental can help the situation if they allow people to change their houses according to their needs and give people some financial stake in the process of maintenance. This helps, because renting is often a step along the way to home ownership; but unless tenants can somehow recover their investments in money and labor, the hopeless cycle of degeneration of rental property and the degeneration of the tenants’ financial capability will continue. (Cf. Rolf Goetze, “Urban Housing Rehabilitation,” in Turner and Fichter, eds., The Freedom to Build , New York: Macmillan, 1972.)

A common element in all these cases is the understanding that the successful development of a household’s “home” depends upon these features: Each household must possess a clearly defined site for both a house and an outdoor space, and the household must own this site in the sense that they are in full control of its development.

Therefore:

Do everything possible to make the traditional forms of rental impossible, indeed, illegal. Give every household its own home, with space enough for a garden. Keep the emphasis in the definition of ownership on control, not on financial ownership. Indeed, where it is possible to construct forms of ownership which give people control over their houses and gardens, but make financial speculation impossible, choose these forms above all others. In all cases give people the legal power, and the physical opportunity to modify and repair their own places. Pay attention to this rule especially, in the case of high density apartments: build the apartments in such a way that every individual apartment has a garden, or a terrace where vegetables will grow, and that even in this situation, each family

every garden is better, when all the patterns which it needs are compressed as far as it is possible for them to be. The building will be cheaper; and the meanings in it will be denser.

It is essential then, once you have learned to use the language, that you pay attention to the possibility of compressing the many patterns which you put together, in the smallest possible space. You may think of this process of compressing patterns, as a way to make the cheapest possible building which has the necessary patterns in it. It is, also, the only way of using a pattern language to make buildings which are poems.

xliv

can build, and change, and add on to their house as they wish.

For the shape of the house, begin with building complex (95). For the shape of the lot, do not accept the common notion of a lot which has a narrow frontage and a great deal of depth. Instead, try to make every house lot roughly square, or even long along the street and shallow. All this is necessary to create the right relation between house and garden—half-hidden garden (ill).

the workgroups, including all kinds of workshops and offices and even children’s learning groups;

80. SELF-GOVERNING WORKSHOPS AND OFFICES 8 I. SMALL SERVICES WITHOUT RED TAPE

82. OFFICE CONNECTIONS

83. MASTER AND APPRENTICES

84. TEENAGE SOCIETY

85. SHOPFRONT SCHOOLS

86. children’s home

397

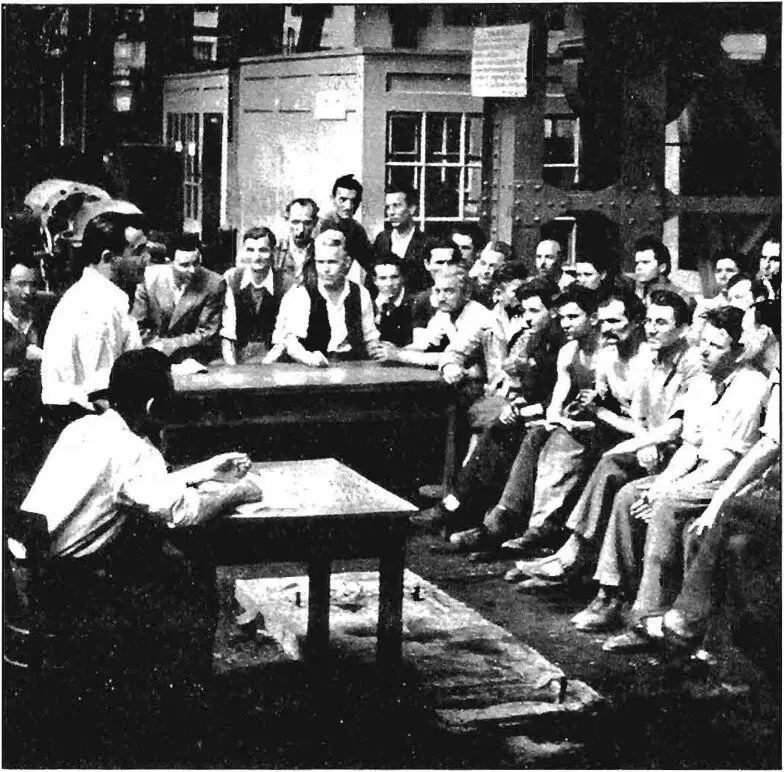

80 SELF-GOVERNING WORKSHOPS AND OFFICES**

398

. . . all kinds of work, office work and industrial work and agricultural work, are radically decentralized by scattered work(9), and industrial ribbons(42) and grouped in small communities— work community(41). This pattern helps to generate these larger patterns by giving the fundamental nature of all work organizations, no matter what their type.

❖ ❖ •!-

No one enjoys his work if he is a cog in a machine.

A man enjoys his work when he understands the whole and when he is responsible for the quality of the whole. He can only understand the whole and be responsible for the whole when the work which happens in society, all of it, is undertaken by small self-governing human groups; groups small enough to give people understanding through face-to-face contact, and autonomous enough to let the workers themselves govern their own affairs.

The evidence for this pattern is built upon a single, fundamental proposition: work is a form of living, with its own intrinsic rewards; any way of organizing work which is at odds with this idea, which treats work instrumentally, as a means only to other ends, is inhuman. Down through the ages people have described and proposed ways of working according to this proposition. Recently, E. F. Schumacher, the economist, has made a beautiful statement of this attitude (E. F. Schumacher, “Buddhist Economics,” Resurgence , 275 Kings Road, Kingston, Surrey, Volume I, Number 11, January, 1968).

The Buddhist point of view takes the function of work to be at least threefold: to give a man a chance to utilize and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his ego-centcredness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence. Again, the consequences that flow from this view are endless. To organize work in such a manner that it becomes meaningless, boring, stultifying, or nerve-racking for the worker would be little short of criminal; it would indicate a greater concern with goods than with people, an evil lack of compassion and a soul-destroying degree of attachment to the most

TOWNS

primitive side of this worldly existence. Equally, to strive for leisure as an alternative to work would be considered a complete misunderstanding of one of the basic truths of human existence, namely, that work and leisure are complementary parts of the same living process and cannot be separated without destroying the joy of work and the bliss of leisure.

From the Buddhist point of view, there are therefore two types of mechanization which must be clearly distinguished: one that enhances a man’s skill and power and one that turns the work of man over to a mechanical slave, leaving man in a position of having to serve the slave. How to tell the one from the other? “The craftsman himself,” says Ananda Coomaraswamy, a man equally competent to talk about the Modern West as the Ancient East, “the craftsman himself can always, if allowed to, draw the delicate distinction between the machine and the tool. The carpet loom is a tool, a contrivance for holding warp threads at a stretch for the pile to be woven round them by the craftsmen’s fingers; but the power loom is a machine, and its significance as a destroyer of culture lies in the fact that it does the essentially human part of the work.” It is clear, therefore, that Buddhist economics must be very different from the economics of modern materialism, since the Buddhist sees the essence of civilization not in a multiplication of wants but in the purification of human character. Character, at the same time, is formed primarily by a man’s work. And work, properly conducted in conditions of human dignity and freedom, blesses those who do it and equally their products. The Indian philosopher and economist J. C. Kumarappa sums the matter up as follows:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.