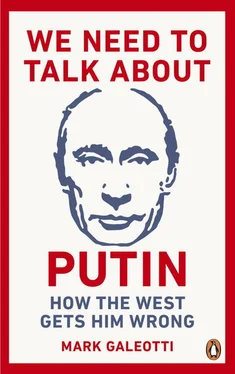

Because the irony is that, for all that he has been a fixture of global politics for almost twenty years now, for all that there are biographies of his life and calendars of his bare-chested antics and for all that he is a familiar subject of satirists and pundits alike, we still don’t really know who he is. Ruthless autocrat or saviour of a beleaguered nation? KGB veteran or pious Christian? Brooding grandmaster of global geopolitics or self-indulgent kleptocrat? He’s a bit of each of them, but none of these labels truly sum him up – and that’s partly the point. Putin is ferociously private – not just on his own account, but also on behalf of his family, both out of preference and political calculation; his aloofness allows everyone to construct their own personal Putin.

Part of my motivation to write this book is a frustration with the simplistic caricatures so often deployed – and not only in the West – to try and understand him. I remember one newly appointed European ambassador to Moscow blithely asserting that ‘to understand Putin, you simply need to understand his KGB training’. If it is that simple, then why do we keep getting Putin wrong? The main drivers for this process of estrangement with Russia may be elsewhere, but it is also depressingly clear how often Western diplomacy has failed. It left a potential pragmatic ally in the early 2000s sufficiently embittered that by 2007 Putin was squaring up for a confrontation. Its toothless response to Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia was used as evidence in Moscow in 2014 that moving into Ukraine would lead to only brief and token protest. It even managed to convince not just Putin but also many within his political establishment that the West was at once too weak to fear and yet too dangerous to ignore. Above all, it failed to persuade them that we do not hate them, their country and their culture. All this happened in no way only or even mainly because of our poor handling of Putin and Russia – but we have managed to handle both badly, and to a large extent because of a lack of understanding.

In this book, I seek to present a picture of the complexities of Vladimir Putin, and through him of today’s Russia, drawing on more decades of contact with Russia than I’d care to admit – time spent travelling there, talking to everyone from provincial cops to Moscow officials, getting drunk and paying the odd bribe. I don’t for a minute think that I have got everything right, nor that everyone else has got everything wrong. This is not primarily a book for my academic colleagues, and I will beg their indulgence for its tone, brevity and distinct absence of footnotes. Rather, it is for anyone who is curious about who this enigmatic figure may be, and why there is so much hype and hysteria around him. By attacking a collection of the most common and most problematic myths that ‘everyone knows’ about Putin, I hope to try and cut through some of the most unhelpful. Of course, I am, in part, taking on straw man arguments and over-simplifications, and it is not as though every policymaker, scholar or pundit believes all or even most of these. That said, the recent impoverishment of much public discourse about Putin and Russia, with cliché and caricature increasingly mobilised on both sides, has been depressing. As the world gets more complex, the ways we frame and explain it too often seem to be getting simpler and less nuanced. That is something we need to talk about, too – but not before we’ve finished talking about Putin.

A Guide to Further Reading

As I say, this book does not pretend to be the last word on Putin, and nor does it claim that no one else gets it right. Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy’s Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin (Brookings Institution Press, 2013) is a sharp take on the idea of ‘various Putins’ that also manages to win my heart by its use of a Mr Benn motif (for those who grew up watching children’s television in 1970s Britain). Brian Taylor’s The Code of Putinism (Oxford University Press, 2018) draws particularly on official statements to create a good sense of the kind of world view held by Putin and his closest allies. Anna Arutunyan’s The Putin Mystique: Inside Russia’s Power Cult (Skyscraper Publications, 2014) looks at the Russian people, and how far their dreams and fears actually shaped Putin and his regime. Mikhail Zygar’s All The Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin (PublicAffairs, 2016) is a brilliant study less of Putin himself and more of the key figures around him. Indeed, it also seems important to stress that Russia is bigger than Putin – Tony Wood’s Russia Without Putin: Money, Power and the Myths of the New Cold War (Verso, 2018) does this especially well.

Chapter 1: Putin Is a Judoka, Not a Chess Player

There’s snow, there are bears, there’s vodka – and then there’s chess, one of the irritatingly durable clichés for Russia and Russians. Consider the classic Russian film villains: there’s the brutish thug, of course, but there’s also the unemotional chess player, ten moves ahead of his rival. American politicians seem especially to love this metaphor. During Barack Obama’s presidency, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Rogers complained that ‘Putin is playing chess and I think we are playing marbles.’ More recently, Hillary Clinton asserted that Donald Trump ‘is playing checkers and Putin is playing three-dimensional chess’.

Of course, this is not actually about chess. The prevailing tendency of seeing Putin as a Machiavellian grandmastermind plays to a Western fear that he is behind everything that goes wrong, and that each setback is part of some complex Russian strategy. Donald Trump’s election, Brexit, the rise of populism in Europe, the migrant crisis and even football hooliganism have all at some point been blamed on Moscow; as a result, we run the risk of giving him too much power. As will be discussed in a later chapter, much of Putin’s international adventurism is bluff, a little like the way an animal when confronted by a predator may puff itself up or bristle its fur to look as big and formidable as possible. We have a tendency to not look past the bristle.

There is no denying that Moscow is often trying to manipulate elections and widen social division in the West, although – as we will see later – rarely with anything like the kind of impact that we sometimes fear. But the main point is that this all implies some fiendishly subtle long-term plan to take the world step by step where Putin, the archetypal Bond villain, only without a lair in an extinct volcano, wants it to go.

In fact, there is no evidence that Putin plays chess, and in any case, it is not his sort of game. Chess is a contest of inflexible rules, transparency and of an intellectual competition where the options are strictly constrained. Everyone starts with the same pieces, and everyone knows what a pawn can do and when it’s their turn to move. Putin doesn’t want to limit his options like that. He does know judo, however. A black belt, he has been honing his skills since starting as a teenager, and his approach to statecraft seems to reflect this. A judoka may well have prepared for a rival’s usual moves and worked out countermoves in advance, but much of the art is in using the opponent’s strength against him to seize the moment when it appears. In this respect, in geopolitics as in judo, Putin is an opportunist. He has a sense of what constitutes a win, but no predetermined path towards it. He relies on quickly seizing any advantage he sees, rather than on a careful strategy.

As a result, both he and the Russian state he has shaped are often unpredictable, sometimes even acting in contradictory ways, especially regarding foreign policy. Many apparent short-term ‘successes’ prove to be long-term liabilities, having been neither thought through beforehand or followed through afterwards. But this helps explain why we are so often unable to predict Putin’s moves in advance – he himself doesn’t know what he’ll do next. Instead, he circles us in the ring. He is aware that overall and when united, the West is so much more powerful than Russia, with twenty times its gross domestic product, six times the population, and more than three times as many troops. But he’s waiting for us to make a mistake and give him what looks like a good chance to strike.

Читать дальше