This, to my thinking, actually represented the great nexus of the Intelligence Community and the tech industry: both are entrenched and unelected powers that pride themselves on maintaining absolute secrecy about their developments. Both believe that they have the solutions for everything, which they never hesitate to unilaterally impose. Above all, they both believe that these solutions are inherently apolitical, because they’re based on data, whose prerogatives are regarded as preferable to the chaotic whims of the common citizen.

Being indoctrinated into the IC, like becoming expert at technology, has powerful psychological effects. All of a sudden you have access to the story behind the story, the hidden histories of well-known, or supposedly well-known, events. That can be intoxicating, at least for a teetotaler like me. Also, all of a sudden you have not just the license but the obligation to lie, conceal, dissemble, and dissimulate. This creates a sense of tribalism, which can lead many to believe that their primary allegiance is to the institution and not to the rule of law.

I wasn’t thinking any of these thoughts at my Indoc session, of course. Instead, I was just trying to keep myself awake as the presenters proceeded to instruct us on basic operational security practices, part of the wider body of spy techniques the IC collectively describes as “tradecraft.” These are often so obvious as to be mind-numbing: Don’t tell anyone who you work for. Don’t leave sensitive materials unattended. Don’t bring your highly insecure cell phone into the highly secure office—or talk on it about work, ever. Don’t wear your “Hi, I work for the CIA” badge to the mall.

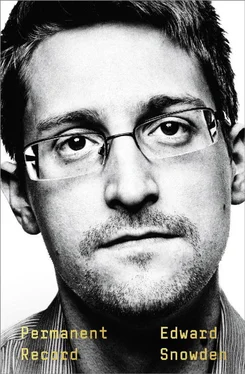

Finally, the litany ended, the lights came down, the PowerPoint was fired up, and faces appeared on the screen that was bolted to the wall. Everyone in the room sat upright. These were the faces, we were told, of former agents and contractors who, whether through greed, malice, incompetence, or negligence failed to follow the rules. They thought they were above all this mundane stuff and their hubris resulted in their imprisonment and ruin. The people on the screen, it was implied, were now in basements even worse than this one, and some would be there until they died.

All in all, this was an effective presentation.

I’m told that in the years since my career ended, this parade of horribles—of incompetents, moles, defectors, and traitors—has been expanded to include an additional category: people of principle, whistleblowers in the public interest. I can only hope that the twenty-somethings sitting there today are struck by the government’s conflation of selling secrets to the enemy and disclosing them to journalists when the new faces—when my face—pop up on the screen.

I came to work for the CIA when it was at the nadir of its morale. Following the intelligence failures of 9/11, Congress and the executive had set out on an aggressive reorganization campaign. It included stripping the position of director of Central Intelligence of its dual role as both head of the CIA and head of the entire American IC—a dual role that the position had held since the founding of the agency in the aftermath of World War II. When George Tenet was forced out in 2004, the CIA’s half-century supremacy over all of the other agencies went with him.

The CIA’s rank and file considered Tenet’s departure and the directorship’s demotion as merely the most public symbols of the agency’s betrayal by the political class it had been created to serve. The general sense of having been manipulated by the Bush administration and then blamed for its worst excesses gave rise to a culture of victimization and retrenchment. This was only exacerbated by the appointment of Porter Goss, an undistinguished former CIA officer turned Republican congressman from Florida, as the agency’s new director—the first to serve in the reduced position. The installation of a politician was taken as a chastisement and as an attempt to weaponize the CIA by putting it under partisan supervision. Director Goss immediately began a sweeping campaign of firings, layoffs, and forced retirements that left the agency understaffed and more reliant than ever on contractors. Meanwhile, the public at large had never had such a low opinion of the agency, or such insight into its inner workings, thanks to all the leaks and disclosures about its extraordinary renditions and black site prisons.

At the time, the CIA was broken into five directorates. There was the DO, the Directorate of Operations, which was responsible for the actual spying; the DI, the Directorate of Intelligence, which was responsible for synthesizing and analyzing the results of that spying; the DST, the Directorate of Science and Technology, which built and supplied computers, communications devices, and weapons to the spies and showed them how to use them; the DA, the Directorate of Administration, which basically meant lawyers, human resources, and all those who coordinated the daily business of the agency and served as a liaison to the government; and, finally, the DS, the Directorate of Support, which was a strange directorate and, back then, the largest. The DS included everyone who worked for the agency in a support capacity, from the majority of the agency’s technologists and medical doctors to the personnel in the cafeteria and the gym and the guards at the gate. The primary function of the DS was to manage the CIA’s global communications infrastructure, the platform ensuring that the spies’ reports got to the analysts and that the analysts’ reports got to the administrators. The DS housed the employees who provided technical support throughout the agency, maintained the servers, and kept them secure—the people who built, serviced, and protected the entire network of the CIA and connected it with the networks of the other agencies and controlled their access.

These were, in short, the people who used technology to link everything together. It should be no surprise, then, that the bulk of them were young. It should also be no surprise that most of them were contractors.

My team was attached to the Directorate of Support and our task was to manage the CIA’s Washington-Metropolitan server architecture, which is to say the vast majority of the CIA servers in the continental United States—the enormous halls of expensive “big iron” computers that comprised the agency’s internal networks and databases, all of its systems that transmitted, received, and stored intelligence. Though the CIA had dotted the country with relay servers, many of the agency’s most important servers were situated on-site. Half of them were in the NHB, where my team was located; the other half were in the nearby OHB. They were set up on opposite sides of their respective buildings, so that if one side was blown up we wouldn’t lose too many machines.

My TS/SCI security clearance reflected my having been “read into” a few different “compartments” of information. Some of these compartments were SIGINT (signals intelligence, or intercepted communications), and another was HUMINT (human intelligence, or the work done and reports filed by agents and analysts)—the CIA’s work routinely involves both. On top of those, I was read into a COMSEC (communications security) compartment that allowed me to work with cryptographic key material, the codes that have traditionally been considered the most important agency secrets because they’re used to protect all the other agency secrets. This cryptographic material was processed and stored on and around the servers I was responsible for managing. My team was one of the few at the agency permitted to actually lay hands on these servers, and likely the only team with access to log in to nearly all othem.

In the CIA, secure offices are called “vaults,” and my team’s vault was located a bit past the CIA’s help desk section. During the daytime, the help desk was staffed by a busy contingent of older people, closer to my parents’ age. They wore blazers and slacks and even blouses and skirts; this was one of the few places in the CIA tech world at the time where I recall seeing a sizable number of women. Some of them had the blue badges that identified them as government employees, or, as contractors called them, “govvies.” They spent their shifts picking up banks of ringing phones and talking people in the building or out in the field through their tech issues. It was a sort of IC version of call-center work: resetting passwords, unlocking accounts, and going by rote through the troubleshooting checklists. “Can you log out and back in?” “Is the network cable plugged in?” If the govvies, with their minimal tech experience, couldn’t deal with a particular issue themselves, they’d escalate it to more specialized teams, especially if the problem was happening in the “Foreign Field,” meaning CIA stations overseas in places like Kabul or Baghdad or Bogotá or Paris.

Читать дальше