However, if you believe in free will you can’t truly believe in social science and economic projection. You cannot predict how people will act. Except, of course, if there is a trick, and that trick is the cord on which neoclassical economics is suspended. You simply assume that individuals will be rational in the future and thus act predictably. There is a strong link between rationality, predictability, and mathematical tractability. A rational individual will perform a unique set of actions in specified circumstances. There is one and only one answer to the question of how “rational” people satisfying their best interests would act. Rational actors must be coherent: they cannot prefer apples to oranges, oranges to pears, then pears to apples. If they did, then it would be difficult to generalize their behavior. It would also be difficult to project their behavior in time.

In orthodox economics, rationality became a straitjacket. Platonified economists ignored the fact that people might prefer to do something other than maximize their economic interests. This led to mathematical techniques such as “maximization,” or “optimization,” on which Paul Samuelson built much of his work. Optimization consists in finding the mathematically optimal policy that an economic agent could pursue. For instance, what is the “optimal” quantity you should allocate to stocks? It involves complicated mathematics and thus raises a barrier to entry by non-mathematically trained scholars. I would not be the first to say that this optimization set back social science by reducing it from the intellectual and reflective discipline that it was becoming to an attempt at an “exact science.” By “exact science,” I mean a second-rate engineering problem for those who want to pretend that they are in the physics department—so-called physics envy. In other words, an intellectual fraud.

Optimization is a case of sterile modeling that we will discuss further in Chapter 17. It had no practical (or even theoretical) use, and so it became principally a competition for academic positions, a way to make people compete with mathematical muscle. It kept Platonified economists out of the bars, solving equations at night. The tragedy is that Paul Samuelson, a quick mind, is said to be one of the most intelligent scholars of his generation. This was clearly a case of very badly invested intelligence. Characteristically, Samuelson intimidated those who questioned his techniques with the statement “Those who can, do science, others do methodology.” If you knew math, you could “do science.” This is reminiscent of psychoanalysts who silence their critics by accusing them of having trouble with their fathers. Alas, it turns out that it was Samuelson and most of his followers who did not know much math, or did not know how to use what math they knew, how to apply it to reality. They only knew enough math to be blinded by it.

Tragically, before the proliferation of empirically blind idiot savants, interesting work had been begun by true thinkers, the likes of J. M. Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, and the great Benoît Mandelbrot, all of whom were displaced because they moved economics away from the precision of second-rate physics. Very sad. One great underestimated thinker is G.L.S. Shackle, now almost completely obscure, who introduced the notion of “unknowledge,” that is, the unread books in Umberto Eco’s library. It is unusual to see Shackle’s work mentioned at all, and I had to buy his books from secondhand dealers in London.

Legions of empirical psychologists of the heuristics and biases school have shown that the model of rational behavior under uncertainty is not just grossly inaccurate but plain wrong as a description of reality. Their results also bother Platonified economists because they reveal that there are several ways to be irrational. Tolstoy said that happy families were all alike, while each unhappy one is unhappy in its own way. People have been shown to make errors equivalent to preferring apples to oranges, oranges to pears, and pears to apples , depending on how the relevant questions are presented to them. The sequence matters! Also, as we have seen with the anchoring example, subjects’ estimates of the number of dentists in Manhattan are influenced by which random number they have just been presented with—the anchor . Given the randomness of the anchor, we will have randomness in the estimates. So if people make inconsistent choices and decisions, the central core of economic optimization fails. You can no longer produce a “general theory,” and without one you cannot predict.

You have to learn to live without a general theory, for Pluto’s sake!

THE GRUENESS OF EMERALD

Recall the turkey problem. You look at the past and derive some rule about the future. Well, the problems in projecting from the past can be even worse than what we have already learned, because the same past data can confirm a theory and also its exact opposite! If you survive until tomorrow, it could mean that either a) you are more likely to be immortal or b) that you are closer to death. Both conclusions rely on the exact same data. If you are a turkey being fed for a long period of time, you can either naïvely assume that feeding confirms your safety or be shrewd and consider that it confirms the danger of being turned into supper. An acquaintance’s unctuous past behavior may indicate his genuine affection for me and his concern for my welfare; it may also confirm his mercenary and calculating desire to get my business one day.

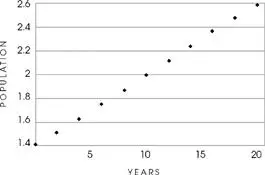

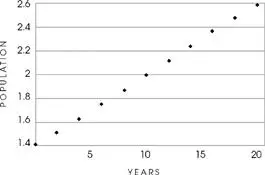

FIGURE 3

A series of a seemingly growing bacterial population (or of sales records, or of any variable observed through time—such as the total feeding of the turkey in Chapter 4).

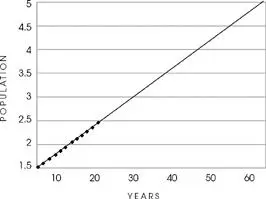

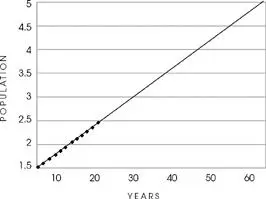

FIGURE 4

Easy to fit the trend—there is one and only one linear model that fits the data. You can project a continuation into the future.

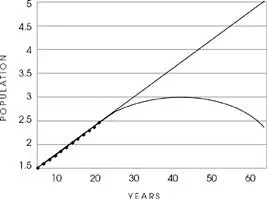

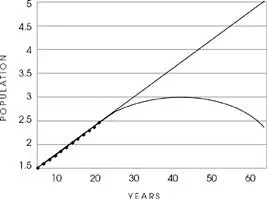

FIGURE 5

We look at a broader scale. Hey, other models also fit it rather well.

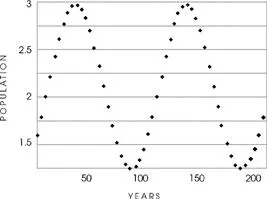

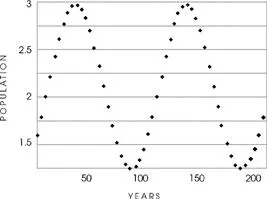

FIGURE 6

And the real “generating process” is extremely simple but it had nothing to do with a linear model! Some parts of it appear to be linear and we are fooled by extrapolating in a direct line. *

So not only can the past be misleading, but there are also many degrees of freedom in our interpretation of past events.

For the technical version of this idea, consider a series of dots on a page representing a number through time—the graph would resemble Figure 1 showing the first thousand days in Chapter 4. Let’s say your high school teacher asks you to extend the series of dots. With a linear model, that is, using a ruler, you can run only a straight line, a single straight line from the past to the future. The linear model is unique. There is one and only one straight line that can project from a series of points. But it can get trickier. If you do not limit yourself to a straight line, you find that there is a huge family of curves that can do the job of connecting the dots. If you project from the past in a linear way, you continue a trend. But possible future deviations from the course of the past are infinite.

Читать дальше