If the notion of civilization helps to explain how China ’s past bears on its present, the fact that it is a continent in size and diversity is critical to understanding how the country functions in practice. There is an essential coherence to the life of the great majority of nation-states that is not true of China. Something major can happen in one part of the country and yet it will have little or no effect elsewhere, or on China as a whole. Major economic changes may appear to have few political consequences and vice versa. The traumatic events in Tiananmen Square in 1989, for example, had surprisingly little impact on the country as a whole. Of course, there are always effects, but the country is so huge and complex that the feedback loops work in strange and unpredictable ways. That is why it is so difficult to anticipate what is likely to happen politically. [610] [610] Pye, ‘Chinese Democracy and Constitutional Development’, pp. 208-10; and Pye, The Spirit of Chinese Politics , pp. 209- 10.

It also perhaps helps to explain a particularly distinctive feature of modern Chinese leaders like Mao and Deng. Whereas in the West consistency is regarded as a desirable characteristic of a leader, the opposite is the case in China: flexibility is seen as a positive virtue and the ability to respond to the logic of a particular situation as a sign of wisdom and an indication of power. Such seeming inconsistency is a reflection of the sheer size of the country and the countless contradictions that abound within its borders. It also has practical benefits, enabling leaders to experiment by pursuing an ambitious set of reforms in a handful of provinces but not elsewhere, as Deng did with his reform programme. Such an approach would be impossible in most nation-states.

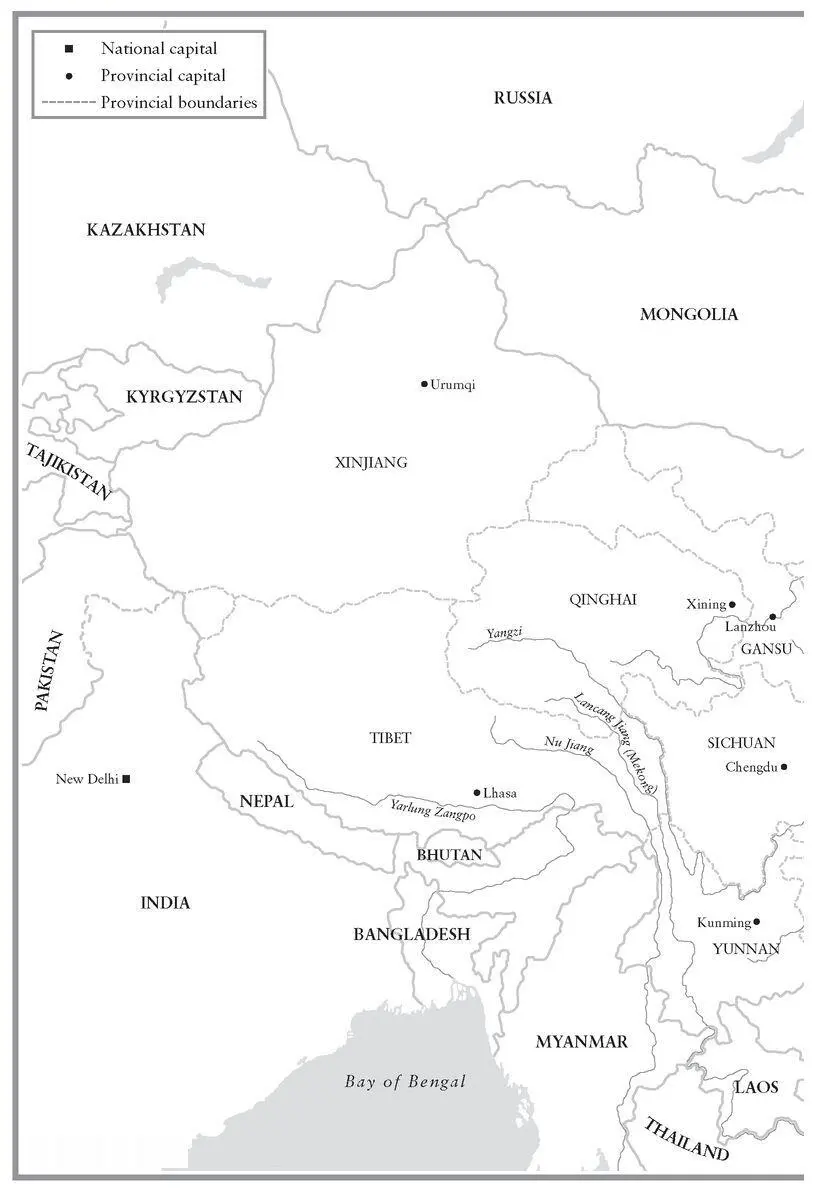

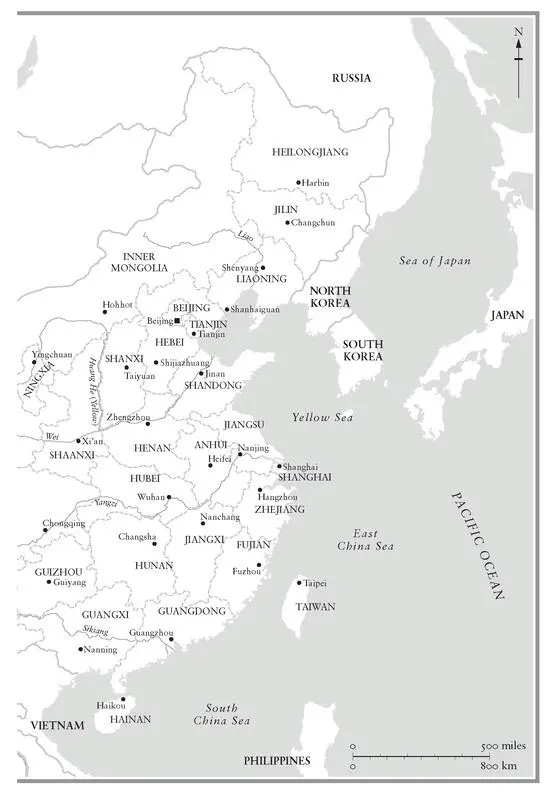

Instead of seeing China through the prism of a conventional nation-state, we should think of it as a continental system containing many semi-autonomous provinces with distinctive political, economic and social systems. There are huge variations between what are, in terms of population, nation-sized provinces. The disparity between the per capita incomes of different provinces is vast, the structure of their economies varies greatly — for example, in their openness to the outside world and the importance of industry — their cultures are distinct, and the nature of their governance is more diverse than one might expect. [611] [611] David S. G. Goodman and Gerald Segal, China Rising: Nationalism and Interdependence (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 32, 44-5.

In many respects, the provinces should be seen as akin to nation-states. [612] [612] Ibid., pp. 31-2.

In fact China ’s provinces are far more differentiated than Europe’s nation-states, even when Eastern Europe and the Balkans are included.

*

Map 9. China’s Provinces

It would be impossible to run a country the size of China by centralized fiat from Beijing. In practice, the provinces enjoy great autonomy. Governance involves striking a balance between the centre and the provinces. Of course everyone recognizes that ultimate power rests with Beijing: but this often means little more than feigned compliance. [613] [613] Pye, ‘Chinese Democracy and Constitutional Development’, pp. 209- 10.

The provinces and cities accept Beijing ’s word, while often choosing to ignore it, with central government fully aware of this. [614] [614] Minxin Pei recounts a classic example of this concerning Hubei province and former Premier Zhu Rongji. See his ‘How One Political Insider is Using His Influence to Push Rural Reforms’, South China Morning Post , 2 January 2003.

Although China has a unitary structure of government, in reality its modus operandi is more that of a de facto federal system. [615] [615] Zheng Yongian, Will China Become Democratic? , p. 329.

This is true in terms of important aspects of economic policy and is certainly the case with the maintenance of social order: the regime expects each province to be responsible for what happens within its borders and not to allow any disruption to cross those borders. The fundamental importance of the relationship between Beijing and the provinces is well illustrated by the fact that the dominant fault line of Chinese politics is organized not around the idea of ‘progress’ — which is typically the case in the West, as evinced by the persistent divide between conservatives and modernizers — but around the question of centralization and decentralization. [616] [616] Pye, The Spirit of Chinese Politics , p. 209.

Whether or not to allow greater freedom to the media, or to expand or restrict the autonomy of the provinces, is the dominant pulse to which Beijing beats. One of the key reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping, as discussed in the last chapter, was to grant more freedom to provincial and local governments as a means of encouraging greater economic initiative. The result was a major shift in power from Beijing to the provinces which, by the nineties, had become of such concern to central government that it was largely reversed. [617] [617] Zheng Yongnian, Discovering Chinese Nationalism in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 30–33, 40–41.

THE NATURE OF CHINESE POLITICS

The most impoverished area of debate on China concerns its politics. Any discussion is almost invariably coloured by a value judgement that, because China has a Communist government, we already know the answers to all the important questions. It is a mindset formed in the Cold War that leaves us ill-equipped to understand the nature of Chinese politics or the current regime. In the post-Cold War era, China already presents us with an intriguing and unforeseeable paradox: the most extraordinary economic transformation in human history is being presided over by a Communist government during a period which has witnessed the demise of European Communism. More generally, it is a mistake to see the Communist era as some kind of aberration, involving a total departure from the continuities of Chinese politics. On the contrary, although the 1949 Revolution ushered in profound changes, many of the underlying features of Chinese politics have remained relatively unaffected, with the period since 1978, if anything, seeing them reinforced. Many of the fundamental truths of Chinese politics apply as much to the Communist period as to the earlier dynasties. What are these underlying characteristics?

Politics has always been seen as coterminous with government, with little involvement from other elites or the people. This was true during the dynastic Confucian era and has remained the case during the Communist period. Although Mao regularly mobilized the people in mass campaigns, the nature of their participation was essentially instrumentalist rather than interactive: top-down rather than bottom-up. In the Confucian view, the exclusion of the people from government was regarded as a positive virtue, allowing government officials to be responsive to the ethics and ideals with which they had been inculcated. We should not dismiss these ideas, inimical as they are to Western sensibilities and traditions: the Confucian system constituted the longest-lasting political order in human history and the principles of its government were used as a template by the Japanese, Koreans and Vietnamese, and were closely studied by the British, French and, to a lesser extent, the Americans in the first half of the nineteenth century. Elitist as the Confucian system clearly was, however, it did contain an important get-out clause. While the mandate of Heaven granted the emperor the right to rule, in the event of widespread popular discontent it could be deemed that the emperor had forfeited that mandate and should be overthrown. [618] [618] Pye, The Spirit of Chinese Politics , pp. 13–14, 17.

Читать дальше