There is no doubt that an abundance of fresh meat would have offered a means of salvation to Franklin expedition survivors. As Stefansson argued, Franklin and his officers need only have studied the narratives of two then recent expeditions to have had a command of the situation: “When you compare the John Ross expedition of 1829–33 with the George Back expedition of 1836–37, you have the complete answer to how a polar residence should be managed.” Stefansson conceded, however, that while John Ross had wisely adopted the Inuit diet, he had not demonstrated that whites could be adequately self-supporting, as most of the food had been obtained from the Inuit through barter. In addition, there is evidence that Franklin expedition survivors did procure limited amounts of fresh meat from the Inuit, but pleas for further aid were then rebuffed.

In truth, the large number of survivors disgorged onto King William Island doomed any hopes of securing adequate quantities of fresh meat. Even among the Inuit, episodes of starvation have been documented in the region of King William Island and the adjacent mainland. Schwatka encountered Inuit who he reported were “in great distress for food” and who had already lost one of their number to starvation. He gave them caribou meat. Knud Rasmussen also wrote that, for the Inuit, life is “an almost uninterrupted struggle for bare existence, and periods of dearth and actual starvation are not infrequent.” As late as 1920, Rasmussen documented that eighteen Inuit had died of starvation at Simpson Strait.

More to the point, Stefansson noted the curiously high number of deaths—before the Erebus and Terror were deserted, “while there were still large quantities of food on the ships.” That “scurvy took so heavy a toll” even then, required, he argued, a “special explanation.” If scurvy was indeed the cause of those deaths, then that explanation was almost certainly an enduring faith in the antiscorbutic value of tinned foods. As the historian Richard J. Cyriax stated in his 1939 study of the Franklin expedition: “As tinned preserved meat has no antiscorbutic properties, Goldner’s meat, if perfectly good, would not have prevented scurvy.”

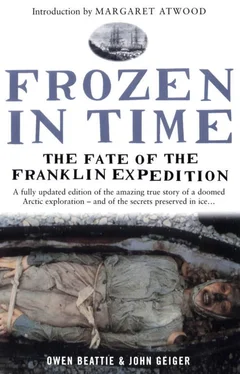

Owen Beattie, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta, believed King William Island might still hold secrets of the Franklin expedition disaster, information that could be exposed by the use of the latest equipment and methods employed in physical anthropology. He believed at least one last pilgrimage in the interests of science was warranted. His initial survey, which would take two Arctic summers to complete, would again follow that rock-strewn trail down which a straggling procession of British seamen had made their desperate retreat.

An aura of doom hung over desolate King William Island during the nineteenth-century visits of M’Clintock, Hall and Schwatka. And for many years after the Franklin disaster, evidence of the tragedy remained fresh. Beattie planned his survey of the island’s south and west coasts in a manner that would be meticulous, even though by 1981, 133 years would have passed since the disaster and he wondered what, of the 105 men who died on the island and in nearby Starvation Cove, endured. He would be the first to apply the techniques of forensic anthropology to investigations into the Franklin expedition.

Beattie had studied archaeology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. As a graduate student, he concentrated on the human skeleton, with advanced training requiring dissection courses in primate and human anatomy. His doctoral research in physical anthropology involved two areas of study: the analysis of hundreds of prehistoric skeletons from the northwest coast of North America; and the use of chemical analysis of bone to aid in the identification of modern human remains relating to forensic investigations. After joining the University of Alberta in 1980, his primary interests continued to grow in the area of human identification studies, or forensic anthropology, a subdiscipline of physical anthropology.

Although the Franklin expedition’s failure was of considerable historical importance, it was first and foremost a mass disaster, involving multiple human deaths linked to a single, catastrophic event. It represented an unresolved forensic case, a fact in no way altered by the time that had passed. (If such a tragedy were to occur today, it would be investigated along precisely the same lines as would the carnage resulting from, for example, a modern-day train wreck, fire or airplane crash, using exactly the same scientific techniques to interpret skeletal and preserved soft tissue remains.) Given this fact, Beattie planned to collect any skeletal remains found on King William Island, then try to identify physical evidence that would support or disprove the conventional view of the expedition’s destruction through starvation and scurvy. He intended to look for information on health and diet, for indications of disease, for evidence of violence and for information as to each individual’s age and stature. There was also a remote chance that a victim’s identity could be established, through dental features such as gold teeth and crowns, or through personal belongings found in association with a body.

Because of his special training in forensic anthropology relating to human identification, Beattie had assisted in numerous investigations conducted by medical examiner’s offices, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and other police agencies, and had testified in court as an expert witness. On King William Island, he planned to apply this expertise to a far older and greater mystery.

Beattie prepared for his Arctic journeys by studying sites identified by nineteenth-century searchers, and on 25 June 1981, set out from his cramped office on the thirteenth floor of the Henry Marshall Tory Building on the University of Alberta campus in Edmonton to investigate the Franklin expedition sites for the first time. First, he boarded a Boeing 727 to Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories, then flew on past the Arctic Circle to the central Arctic transportation centre of Resolute, a tiny community of 168 people nestled on the south coast of Cornwallis Island. Travelling with Beattie was co-investigator and Arctic archaeologist James Savelle.

A truck from the Polar Continental Shelf Project picked up the two researchers at the terminal in Resolute; they were then driven to nearby barracks where they met up with field assistant Karen Digby. The Polar Shelf, an agency of the Canadian government, provides a vital service by supplying scientists and researchers in Canada’s far north with logistical and air support. Beattie, Savelle and Digby soon met Polar Shelf base-manager Fred Alt, picked up a short-wave radio, a 30.06 rifle and 12-gauge shotgun, and prepared for a Twin Otter aircraft to carry them into the field.

From Resolute, the research team flew to Gjoa Haven, an Inuit community on the southeast coast of King William Island, where Inuit students Kovic Hiqiniq and Mike Aleekee joined the team as assistants. Hiqiniq and Aleekee arranged for two hunters to carry the researchers and their equipment by snowmobile the next day, south across ice-clogged Simpson Strait. There, at Starvation Cove, an inlet on the North American mainland that sprawls and meanders inland for several miles, it is believed that the last of Franklin’s men perished.

On 27 June 1981, the five researchers made the gruelling twelve-hour journey over hillocks and cracks in the ice on komatiks, traditional sledges once hauled by dog teams, but in this case pulled by snowmobiles. Sitting atop a mound of equipment and supplies, each firmly grasped hold of both sides of the komatik, as every icy obstacle along the way threatened to dislodge them. Joining them on the journey was the wife of one of the hunters carrying an infant tucked inside her amauti, or hooded parka. The temperature was seasonal, hovering between zero and 41°F (-17.5°C and 5°C).

Читать дальше