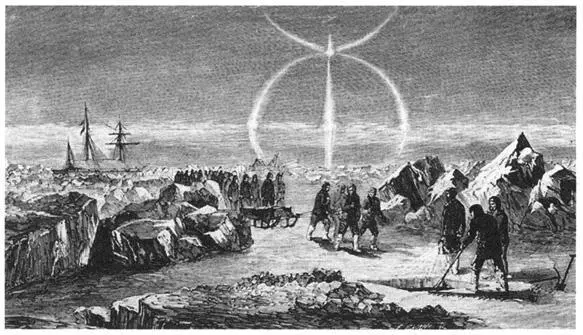

ABOVE Franklin’s men lie dying beside the boat with which they had planned to ascend the Back River, King William Island. Oil painting by W.T. Smith

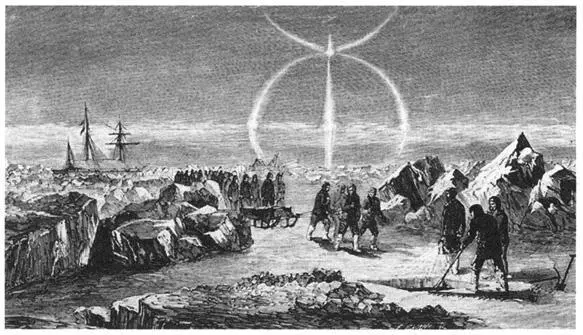

BELOW Burial in mid-winter, from M’Clintock’s voyage aboard the Fox .

The success of their voyage brought both honour and fame to M’Clintock and Hobson, as well as some solace to Lady Franklin. She now knew the exact date of Franklin’s death and that he had died aboard-ship long before the final, gruesome events on King William Island, thus preserving his reputation. What is more, he had died close enough to his objective to have justified at least a moral claim to the prize: Discoverer of the Northwest Passage. M’Clintock had produced, it was popularly decided, “melancholy evidence of their success.” Sherard Osborn, who had commanded a ship in an earlier search, captured the public mood when he wrote of Franklin:

Oh, mourn him not! unless you can point to a more honourable end or a nobler grave. Like another Moses, he fell when his work was accomplished, with the long object of his life in view.

The burial of Franklin. Depicted on the monument erected to him at Waterloo Place, London.

In Toronto, the Globe echoed:

Sir John, we now know, sleeps his last sleep by the shores of those icy seas whose barriers he invyain essayed to overcome. He died, as British seamen love to die, at the post of duty. Surrounded, let us hope, by his gallant officers, who, while he lived, would minister to his every want, and when dead would bear him to his cold and lonely tomb in some rocky bay, with saddened hearts and tear-bedewed eyes.

Finally, on 15 October 1859, the Illustrated London News attempted to recapture the emotions felt by Franklin’s sailors near Victory Point in their final desperate struggle to survive:

Awfully impressing must it have been to Lieutenant Hobson, and subsequently Captain M’Clintock, when they thus stood upon the intrenched scene where their gallant countrymen had, eleven years previously, prepared themselves for that last terrible struggle for life and home. Who shall tell how they struggled, how they hoped against hope, how the fainting few who reached Cape Herschel threw themselves on their knees and thanked their God that, if it so pleased Him that England and home should never be reached! He had granted to them the glory of securing to their dear country the honour they had sought for her—the discovery of the Northwest Passage.

In their last final march, the crews of the Erebus and Terror had indeed discovered the Northwest Passage. But by the time they walked along the shores of Simpson Strait, the triumph must have been a hollow one, for all around them was despair.

Franklin and his crews entered the Arctic with their primary goal the completion of the passage. Although geographically there is no single passage, and on a map it is possible to plot a myriad of routes around and through the clusters of islands that make up the Arctic archipelago, in reality, until the advent of ice-breakers, ice conditions narrowed the possibilities to only a few choices. By 1845, when Franklin sailed, much of the mainland coast of North America had been charted by overland explorers questing for a navigable passage, and when the ship-based explorations up to that point are added to the map of the Arctic, it becomes apparent that only a relatively short distance, in the King William Island region, remained uncharted.

In their first season in the Arctic, Franklin’s ships sailed up Wellington Channel to 77°N latitude where they were turned back either by ice or the lateness of the season. The expedition then travelled south to Barrow Strait by a previously unexplored channel between Bathurst and Cornwallis islands. Wrote M’Clintock: “Seldom has such an amount of success been accorded to an Arctic navigator in a single season, and when the Erebus and Terror were secured at Beechey Island for the coming winter of 1845–46, the results of their first year’s labour must have been most cheering.” When the sailing season of 1846 began with the break-up of ice in Barrow Strait and in Erebus Bay (their winter harbour off Beechey Island), the two ships sailed roughly south and west, ending beset in the ice off the northwest coast of King William Island in September 1846. What route the ships took to reach this point is still a matter of conjecture, though it is likely the Erebus and Terror travelled through Peel Sound and what is now Franklin Strait between Somerset and Prince of Wales islands. Franklin believed this route would eventually lead him to parts of the mainland coastline he had explored two decades earlier. His maps told him that, in the King William Island area, he had to complete the stretch along the west side of what was then called King William’s Land (a distance M’Clintock estimated at 90 miles/145 km—but, in fact, was actually 62 miles/100 km) to be credited with completing the charting of a Northwest Passage.

The northern extent of this unknown gap was a low point of land on the northwest coast of King William Island, visited by James Clark Ross from the east in the late spring of 1830. Ross had named the location Victory Point. The southern extent was to be found at Cape John Herschel on the south coast of King William Island. In 1839, Peter Warren Dease and Thomas Simpson explored along the mainland coast; moving eastward along the coast to Boothia Peninsula, they eventually turned back to the south coast of King William Island, exploring the island until they reached Cape John Herschel, where they built a large cairn. From this point they crossed back to the mainland and retraced their route to the west, a route which itself had been extended over time to Bering Strait, the western entrance to the passage.

Curiously, perhaps tragically, both Ross in 1830 and Dease and Simpson in 1839 suggested that the area they had explored was an extension of the mainland—a bulge of land connected directly to the southwestern part of Boothia Peninsula. It is very likely that Franklin, armed with the maps, descriptions and opinions of these earlier explorers as well as his own theories on the geography of the region, believed he had no choice in sailing direction when he eventually encountered Cape Felix, the northern tip of King William Island. Thinking that a route to the east of this point would lead to a dead end, he turned his ships to the southwest, directly into the continuously replenished pack-ice that grinds down the length of McClintock Channel from the northwest. The power and persistence of this ploughing train of ice cannot be overestimated; the northwest coast of King William Island bears the scars as proof. This ice mass does not always clear during the short summers and a lethal trap awaited the two ships, a trap made all the more cruel with the realization that the route along the eastern coast of the island regularly clears during the summer. It was only during their final doomed march that the surviving men from the Erebus and Terror completed the gap—and the Northwest Passage. In the words of searcher Sir John Richardson, “they forged the last link of the Northwest Passage with their lives.”

M’Clintock’s discoveries on King William Island thus provided an outline of the expedition’s last days. And with this new information, the final clamour for answers to the Franklin mystery died down, even though it was apparent that many questions remained. As the Illustrated London News was to explain on 1 January 1881: “[M’Clintock’s] search was necessarily a hasty and partial one, as the snow lay thick on the ground, and the parties had to return to their vessel before the disruption of the ice in summer.”

Читать дальше