* * *

Generally speaking, the defences of Khazar fortresses were rather feeble when compared with those raised by the Byzantine Empire. The only exceptions were perhaps found in what is now Daghestan; elsewhere, Khazar builders placed their walls directly on the surface of the ground, making them easy to undermine. Often they also had their gates positioned so that an attacking enemy could approach with his shields facing the defenders, making the task of defence more difficult; this can be seen at the Süren fortress near Bakhchysarai in Crimea, which probably served as an outpost for Sarkel itself.

One might summarize by saying that Khazar fortifications were not really capable of resisting serious Byzantine or Islamic assaults. This was probably because fortifications on the steppes were not strategically very important for a state and culture like that of the Khazars. On the other hand, Khazar fortifications in the Crimea would have faced the Byzantines, while those close to Derbent and the Caspian Gates would have faced the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates and their successors, all of whom were at the forefront of siege technology, thus rendering existing Khazar military architecture virtually useless.

Barthold, V.V., & P.B. Golden, ‘Khazar’, in The Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 4 (Leiden & London, 1978) 1172–1181

Brook, K.A., ‘A Brief History of the Khazars,’ in D.N. Korobkin & Y. Halevi (eds), The Kuzari: In Defense of the Despised Faith (Northvale, 1998) xxv–xxxi

Brook, K.A., The Jews of Khazaria (Northvale, 1999)

Dunlop, D.M., The History of the Jewish Khazars (Princeton, 1954)

Fedortchouk, A., ‘Khazars’, in E. Kessler & N. Wenborn (eds), A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations (Cambridge, 2005) 252

Frenkel, A., ‘The Jewish Empire in the Land of Future Russia’, in Australian Journal of Jewish Studies, 9 (1995) 142–170

Golb, N., & O. Pritsak, Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century (Ithaca, 1982)

Golden, P.B., ‘The Khazars’, in D. Sinor (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia (Cambridge, 1990) 263–270

Golden, P.B., ‘Khazars’, in M. Tütüncü (ed.), Turkish-Jewish Encounters: Studies on Turkish-Jewish Relations through the Ages (Haarlem, Netherlands, 2001) 29–49

Golden, P.B., ‘Some Notes on the Comitatus in Medieval Eurasia with Special Reference to the Khazars’, in Russian History/Histoire Russe, 28 (2001) 153–170

Golden, P.B., ‘Khazar Turkic Ghulâms in Caliphal Service’, in Journal Asiatique, 292 (2004) 279–309

Gorelik, M.V., ‘Arms and Armour in South-Eastern Europe in the Second Half of the First Millenium AD’, in D. Nicolle (ed.), A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour (Woodbridge, 2002) 127–147

Ibn Fadlan (trans. J.E. Montgomery), Mission to the Volga (New York, 2017)

Koestler, A., The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and Its Heritage (London & New York, 1976)

Lvov, A., ‘Shades of Forgotten Ancestors’, in Midstream, 29 (1983) 49–54

Petrukhin, V.I., ‘The Decline and Legacy of Khazaria’, in P. Urbańczyk (ed.), Europe around the Year 1000 (Warsaw, 2001) 109–122

Shapira, D.Y., ‘Some Notes on Jews and Turks’, in Karadeniz Araştırmaları, 16 (2008) 25–38

Soteri, N., ‘Khazaria: A Forgotten Jewish Empire’, in History Today, 45:4 (April 1995) 10–12

Ya’ari, E., ‘Skeletons in the Closet’, in The Jerusalem Report, 6 (1995) 26–30

Ya’ari, E., ‘Archaeological Finds Add Weight to Claim that Khazars Converted to Judaism’, in The Jerusalem Report, 10 (1999) 8

Yevglevsky, A.V. (et al., eds), Proceedings in Archaeology: The European Steppes in the Middle Ages, Vol. 7. Khazarian Times (Russian with English summaries; Donetsk, 2009)

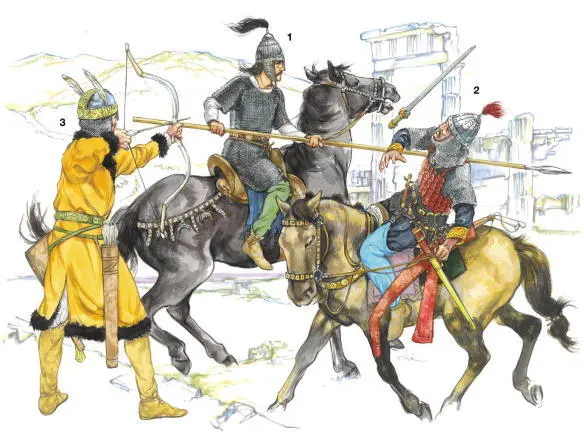

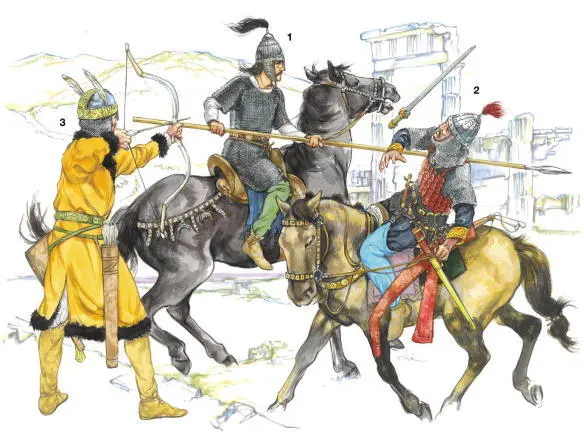

1: Alan armoured cavalryman, 5th C

2: Eastern Hun armoured cavalryman, 4th–5th Cs

3: Western Hun horse archer, 5th C

A1: Alan armoured cavalryman, 5th century

Depicted fighting Huns in the ruins of a Roman town in Crimea, this horseman’s lack of archery equipment shows that he still operates in a style rooted in Iranian cavalry traditions. His ‘splinted’ or lamellar helmet, laced together with rawhide thongs, is of a form which could be found across much of Asia, as far as China and perhaps India, but which was also brought to Europe during the ‘great migrations’ of the early medieval period. He wears a long mail hauberk over a linen tunic, woollen trousers (note broken-line pattern down front), and leather ankle-boots; he has no shield, which was an encumbrance rather than a defence when wielding a heavy spear with both hands. Hidden on his left side is a long, straight sword with a ‘bracket’ slide on its scabbard; silvered bronze fitments would be feasible, perhaps with semi-precious stones on the sword guard. His large Persian horse has a long combed mane, forelock and tail; the harness has silvered bronze ornaments, but the leather-covered wooden saddle lacks stirrups.

A2: Eastern Hun armoured cavalryman, 4th–5th centuries

There were clearly variations between the equipment of elite warriors in different parts of the vast but ephemeral Hun Empire; this warrior represents what is known about the eastern regions. He has a helmet of many directly riveted iron segments, and a small mail hauberk worn beneath a limited form of rawhide lamellar cuirass. He wears silk-covered horseman’s leggings suspended at the front from a belt under his hauberk and tunic, rather than large riding boots. His weapons, apart from a fighting knife hung horizontally in front of his right hip, all hang at his left side. His single-edged sword is a straight ‘palash’ type rather than a curved sabre; his emptied quiver would carry arrows with their flights uppermost, and his bow-case is for an unstrung weapon. He still lacks stirrups, and his saddle, though containing wooden formers, is not yet of the fully wood-framed type. His Turko-Mongol pony has the mane clipped in three tufts, but a long knotted tail.

A3: Western Hun horse archer, 5th century

This dismounted rider from a more western region has a ‘ridge’ helmet which may be of late Roman origin, though now highly decorated with gilt bands in what Romans would have considered a barbarian manner; it also has a mail aventail. His heavy fleece-lined coat hides a mail hauberk, and he wears soft leather leggings with integral feet. Obscured here is a straight, double-edged sword at his left side; its scabbard might have a slide carved from jade and originally from Central Asia. His simple quiver still carries the arrows flights uppermost and thus unprotected, though his bow-case accommodates the weapon when strung.

Alan bow, and case for a strung bow, from Moschevaya Balka, 8th–9th centuries. The bow stave has adopted the typical forwards-curving shape of a reflex bow when unstrung; for a full study, see Osprey Weapons 43, The Composite Bow. (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; photograph David Nicolle)

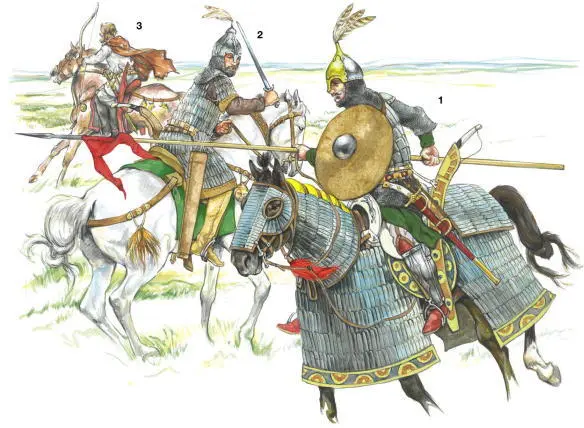

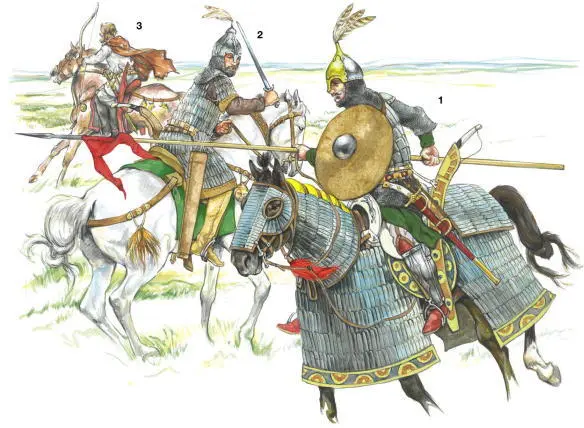

1: Khazar warrior, 7th C

2: Sabirian armoured cavalryman, 6th–7th Cs

3: Western steppes nobleman, 7th C

B1: Khazar warrior, 7th century

Читать дальше