Shafts might also be bound with metal bands to increase their strength when thrusting, and the addition of rawhide or birch-bark bindings gave a more secure grip. To make carrying the spear easier, a rawhide strap was attached (which the Cossacks later called a temyak). Again judging by Cossack fighting styles, the medieval steppe nomads might have fastened a looped leather strap near the butt of the shaft for the rider’s foot, to keep his weapon in an upright position when on horseback.

The methods of using this type of spear could vary, and the following examples are based upon available data:

(1) With a firm grip at the point of balance: the shaft is clamped under the bent arm tightly pressed against the warrior’s body. The effectiveness of the thrust and impact of the lance depended upon the speed of the horse at the moment of contact.

(2) Couched: the shaft is grasped nearer its lower end, and either rests beneath the armpit or is tightly pressed into it, with the arm bent at the elbow in a horizontal position. The result is a significant increase in the effective reach of the lance, but makes it difficult to control in a horizontal position because it is not grasped at the point of balance.

(3) With a free grip: the spear is held in one hand in a horizontal ‘trail’ position. Immediately before the moment of contact, the warrior thrusts his arm in whatever direction he chooses. This results in a weaker impact, but allows the rider to fence with the spear and use it to deflect enemy blows.

(4) With a fixed ‘dart’ grip: the weapon is held overarm in one hand, as if to throw it like a javelin. This permits a downwards blow, and was typical when in combat against men on foot.

Axes

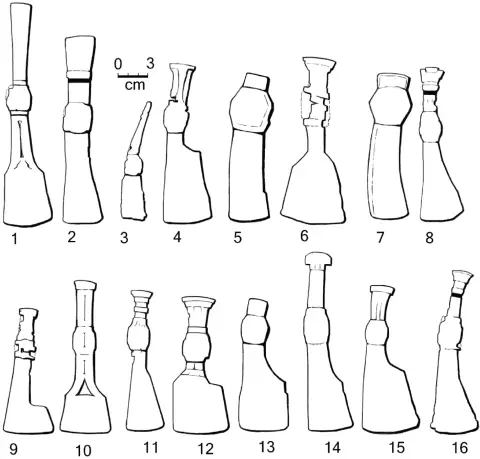

The use of battle-axes by the peoples of the Khazar Khaganate reflected the influence of long-established Caucasian tradition. In fact such axes are not known in early Khazar and Bulgar burials, but are present in large numbers in Alan sites. Under Alan influence, battle-axes subsequently came to be used by the semi-settled Khazar population from at least the 7th century.

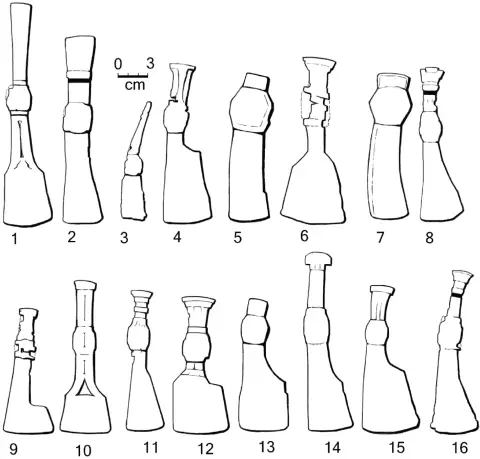

Khazar axeheads: (1, 5, 8, 11, 14 & 16) from Sukhaya Gomolsha; (2 &13) from Netaylovka; (3) from Borisovo; (4) from Topoli; (6, 9 & 12) from Krasnaya Gorka; (7) from Zheltoe; (10) from Kochetok; (15) from Lysiy Gorb. (Drawings by A. Karbivnychyi after V. Kriganov)

The axe was a universal weapon in the sense that it could be used by both horsemen and infantrymen. The handle was made of hardwood such as cornel or maple, normally from 60 to 75cm long (23–30in). In battle the axe’s effectiveness was comparable to that of a sabre, but it was much cheaper to manufacture. (Because axes were the most readily available weapons to the poorest among the population during the early period, little distinction may have been made between a weapon of war and a work-tool.) Nevertheless, all surviving axes are eye-catching weapons, though relatively small in size and weight. Their shapes can be categorized according to the details of both the blade and the socket which fits around the handle, but the majority of war axes from the Saltov culture are of one type, having a narrow, elongated blade; a small number also have a smaller secondary blade on the back of the head.

War-flails

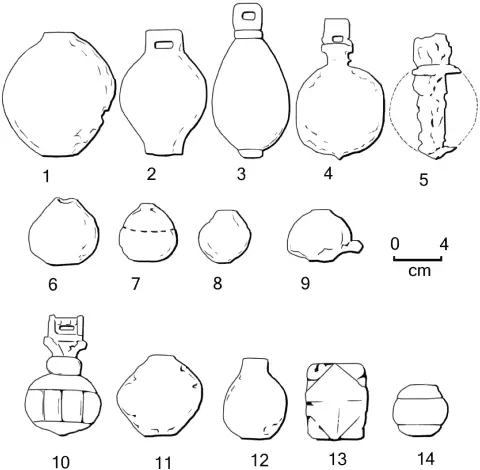

The war-flail was a variety of mace, consisting of a ball or other weight hanging from a short handle by means of a strap, plaited thongs or more rarely a chain. It was not easy to use in combat, requiring considerable room to deliver an effective blow. It was solely an offensive weapon, being useless as a means of defence, so those who used the war-flail may usually have been equipped with shields. Nevertheless, the number of finds suggests that it was effective, perhaps in the hands of both cavalry and infantry in fast-moving skirmishes. Consequently the flail may have been carried as part of a warrior’s full panoply, for use when a suitable occasion arose.

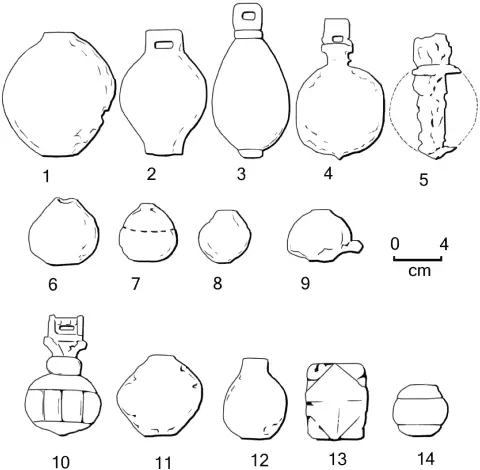

Weights from Khazar war-flails: (1, 7 & 13) from Krasnaya Gorka; (2) from Sarkel; (3) from Oboznoye; (4 & 9) from Verhniy Saltov; (5) from Mayaki; (6, 8, 10–12 & 14) from Sukhaya Gomolsha. (Drawings by A. Karbivnychyi after V. Kriganov)

The war-flails of Khazar warriors may be divided by minor variations; in the most massive form the strap passed through a longitudinal hole in a flange at the top of the weight. The most common type had an oval weight made of bone with an inset iron bar, while other types had a solid weight made entirely of bone, stone, iron, bronze or lead.

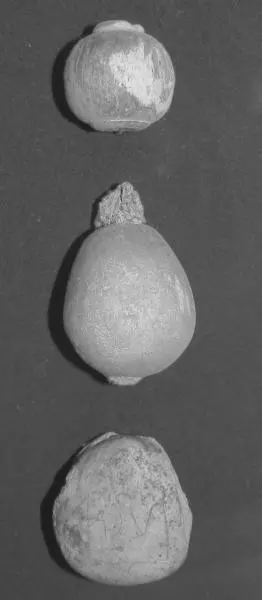

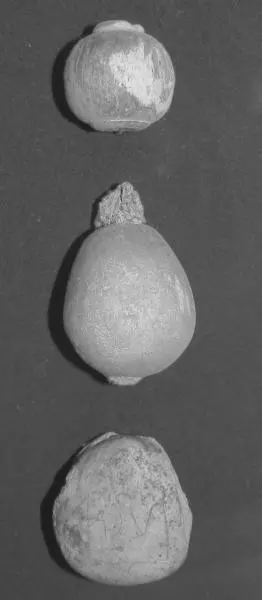

Weights from nomad◦– probably Khazar◦– and early medieval Russian war-flails. (State Historical Museum, Chernihiv; photograph Mikhail Zhirohov)

Body armour

The appearance of armour among the Khazars can be traced back to the end of the 7th century, but the fact that only small fragments of mail have been found in such contexts seems to suggest that, as yet, full mail hauberks were rarely used. Perhaps mail was so expensive, having been imported from elsewhere, that small sections might have been sewn onto a leather or textile basis to protect particularly vulnerable parts of the body? In some warrior burials mail was found together with remnants of lamellar armour. It is probable that in this period efforts were still being made to achieve an optimal design which resulted, by the middle of the 8th century, in the adoption of a full mail hauberk, like those already seen in wealthier and more settled cultures. However, the mail found in Khazar-period graves was often of sophisticated manufacture, combining both riveted and hammer-welded links. The latter are sometimes made of square-section wire, formed into rings with a diameter of 10 to 14mm (0.4–0.5in). In their complete form most mail shirts had short sleeves, and slits in the hem of the skirt to prevent it riding up when astride a horse.

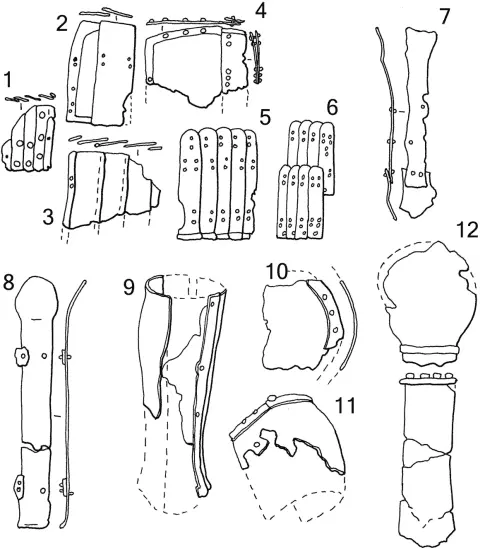

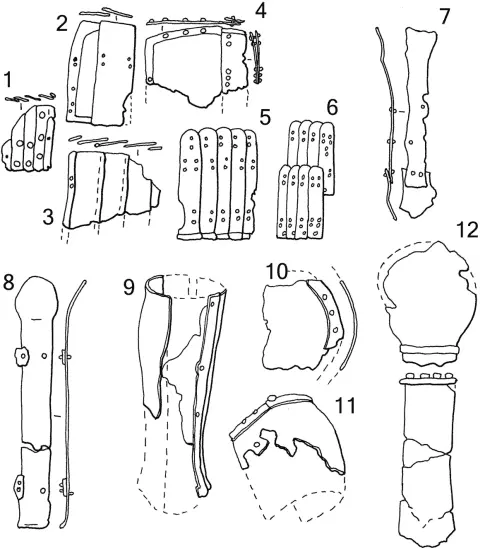

Fragmentary finds of Khazar armour:

(1 & 4) Riveted lamellar armour from Verhniy Chir-Yurt graves, 7th–8th centuries; (2 & 3) unriveted fragments from same site; (5) lamellar armour from Ostryi near Kislovodsk, 7th–8th Cs; (6) lamellar armour from ‘Kozzyi skaly’ on Mt Beshtau, near Pyatigorsk, 9th–10th Cs; (7) splint vambrace from same site; (8) splint greave from same site; (9) iron greave from Borisovskiy graves near Gelendjik, 8th–9th Cs; (10) fragment of iron shoulder plate from Verhniy Chir-Yurt graves, 7th–8th Cs; (11) fragment of iron shoulder plate from Borisovskiy graves, near Gelendjik, 8th–9th Cs; (12) pieces of iron horse chamfron from Dimitrievskiy graves on Severskiy Donets river, 9th–10th centuries. (David Nicolle after Gorelik, 2002)

As pointed out by the Russian historian of arms and armour, Dr M.V. Gorelik, developments in armour were amongst the Khazars’ greatest technological achievements during the 7th to 9th centuries. In fact, the Khazars drew upon the traditions of Central Asia and China, Transoxania, Iran and Byzantium to produce something genuinely new, and the skilled armourers of the north Caucasus ensured that the results were often of the highest quality. [3] Gorelik, M.V., ‘Arms and Armour in South-Eastern Europe in the Second Half of the First Millenium AD’, in D. Nicolle (ed.), A Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour (Woodbridge, 2002) 134.

Читать дальше