Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Toronto, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Hanover Square Press, Жанр: История, Юмористические книги, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hanover Square Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:Toronto

- ISBN:978-1-48805-113-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In 1908, Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge was a passenger in a demonstration flight piloted by Orville Wright. On the fifth circuit flying around Fort Myer in Virginia, the propeller broke and the plane crashed, killing Selfridge (Wright survived). He became the first person in history to be killed in a plane crash.

In 1912, Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of radio, predicted that “the coming of the wireless era will make war impossible, because it will make war ridiculous.” In 1914, the world went to war.

On October 16, 1929, the eminent Yale economist Irving Fisher predicted that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Eight days later, stock markets around the world crashed, as a bubble of speculation fueled by easily available debt finally burst. The global economic depression lasted for years; in the wake of the financial crisis, voters in many democracies increasingly turned to populist authoritarian politicians.

In 1932, Albert Einstein predicted that “there is not the slightest indication that [nuclear energy] will ever be obtainable.”

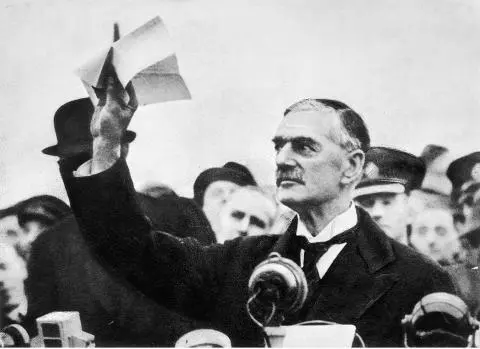

In 1938, the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain returned home with a deal he had just signed with Adolf Hitler and predicted, “I believe it is peace for our time,” before adding, “Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.” In 1939, the world went to war.

In 1945, Robert Oppenheimer, the man who led the efforts to produce the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, wrote, “If this weapon does not persuade men of the need to put an end to war, nothing that comes out of a laboratory ever will.” Contrary to his hopes—and the hopes of Nobel, Gatling, Maxim and Wright—we still have wars, although at least we haven’t actually had a nuclear war yet (statement correct at time of writing), so Oppenheimer maybe wins this one on points.

In 1966, the eminent designer Richard Buckminster Fuller predicted that by the year 2000, “amid general plenty, politics will simply fade away.”

In 1971, the Russian cosmonauts Georgiy Dobrovolski, Viktor Patsayev and Vladislav Volkov became the first people to die in space, after their Soyuz module decompressed on their return from a space station.

In 1977, Ken Olsen, the president of the Digital Equipment Corporation, predicted that the computer business would always be niche, saying, “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.” In 1978, Gary Thuerk, a marketing manager at the Digital Equipment Corporation, sent an unsolicited email plugging his company’s products to around 400 recipients over Arpanet, one of the earliest manifestations of the internet. He had just sent the world’s first spam email. (And according to him, it worked: DEC sold millions of dollars’ worth of machines from their email campaign.)

In 1979, Robert Williams, a worker at a Ford plant in Michigan, became the first person in history to be killed by a robot.

In December of 2007, financial commentator Larry Kudlow wrote in the National Review : “There’s no recession coming. The pessimists were wrong. It’s not going to happen… The Bush boom is alive and well. It’s finishing up its sixth consecutive year with more to come. Yes, it’s still the greatest story never told.” In December of 2007, the US economy entered recession. (At the time of writing, Larry Kudlow is currently serving as the director of the National Economic Council of the United States.) In 2008, stock markets around the world crashed as a bubble of speculation fueled by easily available debt finally burst. The global economic recession lasted for years; in the wake of the financial crisis, voters in many democracies increasingly turned to populist authoritarian politicians.

In August 2016, a 12-year-old boy died, and at least 20 other people from a nomadic group of reindeer herders were hospitalized, after an anthrax outbreak in Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula. Anthrax hadn’t been seen in the region in 75 years; the outbreak happened during a summer heat wave in which temperatures were 25°C above normal. The heat wave melted the thick permafrost that coats Siberia, uncovering and defrosting layers of ice that had formed decades earlier—and which held the frozen carcasses of reindeer that had died in the last anthrax outbreak in 1941.

Ice can keep pathogens preserved—alive, but in stasis—for decades, centuries, perhaps longer. The disease had been lying dormant in the subzero temperatures since the days when the Russian winter was breaking Hitler’s army, just waiting for the time when its frozen cage would melt. That finally happened in 2016 (at the time, the hottest year globally since records began) as the warming world released the bacteria once more, infecting more than 2,000 reindeer before it spilled over into humans.

It’s tempting to say that nobody could have foreseen a disaster so baroque, but in fact five years earlier two scientists had predicted that exactly this would happen as climate change grew worse: that the permafrost would gradually retreat, and would release long-absent historical diseases back into the world as it went. This will only continue as the temperature rises, with the curious effect of rewinding history—back past Thomas Midgley hard at work in his laboratory, back past Eugene Schieffelin standing in a park opening cages, back past William Paterson dreaming of an empire—as the cumulative effects of the Industrial Revolution unspool around us. We don’t know how many people climate change will kill over the coming century, we don’t know in what ways it will change our society, but we do know that at least one of its victims died because an unintended consequence of our decisions as a species was to summon zombie anthrax back from the grave. He probably won’t be the last.

On May 7, 2016—a little under a century and a half after Mary Ward went for a drive one fateful summer’s morning—a man named Joshua Brown was driving down a road near Williston, Florida, in his Tesla Model S, which was in autopilot mode. A later investigation showed that in the 37 minutes of his journey, he had his hands on the wheel for just 25 seconds; he was relying on the car’s software to control the vehicle for the rest of the time. When a truck pulled out into the road, neither Brown nor the software spotted it, and the car crashed into the truck.

Joshua Brown became the first person in the history of the world to die in a self-driving car accident.

Welcome to the future.

EPILOGUE

Fucking Up the Future

In April 2018, a deal was announced to reopen a previously closed coal-fired power plant in Australia. This was unusual for obvious reasons—as the world tries to slowly move away from climate-change-causing fossil fuels, reopening a coal-burning plant seems a strange move—but it was even more unusual because of the main impetus for it being reopened. It was to provide cheap power to a company mining cryptocurrency.

Bitcoin is the most widely known of the cryptocurrencies, but there’s an ever-expanding ecosystem of the things as companies launch new ones at a seemingly exponential rate, hoping to cash in on the mad scramble for digital money. These currencies aren’t “mined” in the way that, say, gold is. They’re just bits of computer code, most of them based on something called blockchain technology, where each virtual coin is not just an item of symbolic value but also a ledger of its own transaction history. The computational power needed to create them in the first place, and to process their increasingly complicated transaction logs, is significant—and, as such, sucks up electricity at a crazy rate, both to run the ever-larger data centers devoted to crypto-mining and to cool them down as they overheat.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.