Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Toronto, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Hanover Square Press, Жанр: История, Юмористические книги, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hanover Square Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:Toronto

- ISBN:978-1-48805-113-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

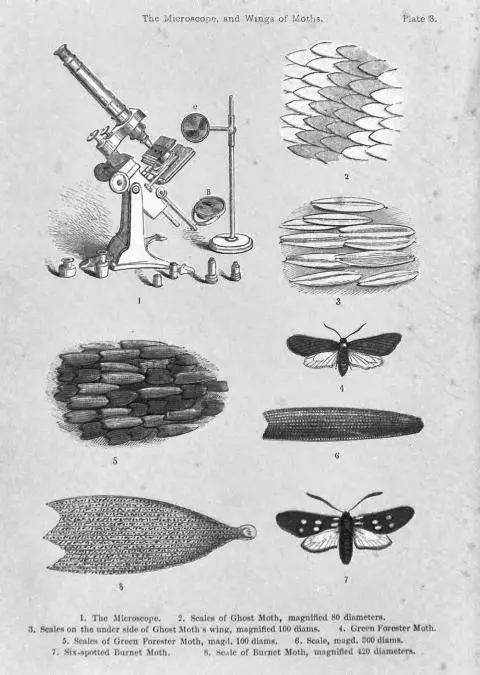

As she grew into adulthood, Mary corresponded with many scientists, and her talent for illustration saw her commissioned to produce illustrations for several of their books. Then in 1857, disappointed with the quality of microscopy books on offer, she decided to print a book of her own drawings. Afraid (not without reason) that no publisher would touch it because she was a woman, she self-published 250 copies. They sold out, and the book came to the attention of a publisher, who believed that the beauty of her illustrations and the quality of her writing meant that, in this one case, perhaps the issue of her sex could be overlooked. Published as A World of Wonders as Revealed by the Microscope , it became a bit of a publishing sensation—reprinted eight times over the coming decade, making it one of the first books in the category that today we might call “popular science.”

That wasn’t the end of her popular science career—she wrote two further books, including a telescope companion to the microscope book, which were displayed at the 1862 Crystal Palace exhibition; she would illustrate numerous other scientific works for eminent scientists; she published articles in several journals, including a well-received study of natterjack toads; and she became one of only three women permitted to be on the Royal Astronomical Society’s mailing list—one of the other two was Queen Victoria. She never got a degree, though, because women weren’t allowed to.

Except… all of this is preamble, because while Mary Ward was a talented woman who led a remarkable life, that’s not why we remember her today. Maybe it should be. But it isn’t, because of what happened in Parsonstown on August 31, 1869. On that day, at the age of 42, she and her husband, Captain Henry Ward, were riding in a steam-powered automobile. This vehicle was a homemade one—she was always surrounded by scientists, so of course it was—built by the sons of her cousin William Parsons.

Riding in a vehicle like this was a new experience at the time, an early sign of the age to come. The steam-powered automobile had been invented a century earlier in France, but this was still years before the advent of anything we’d recognize as a car today. What vehicles there were—hulking, ungainly things that were widely suspected of damaging roads—had caused enough of a sensation that Britain had passed a law regulating their use a few years earlier in 1865, but they were still rare, experimental novelties. Of the billions and billions of humans who’ve ever lived on this planet, Mary Ward was among the first fraction of a fraction of a fraction of a percent to ride in a car.

Records tell that as the vehicle trundled down the Mall in Parsonstown at a speed of three and a half miles an hour, it turned sharply into the corner of Cumberland Street, by the church. Maybe it was simple bad luck. Maybe the road was uneven, not being designed for anything more than a horse and cart. Maybe they weren’t thinking about the concept of “turning too sharply,” because cars and horses handle very differently and the risks aren’t the same. Maybe Mary was simply thrilled by the experience, excited about the possibilities of the future, and she leaned out a bit too far to see the road pass beneath.

Whatever the reason, as the vehicle took the corner, one side of it tipped up slightly, and Mary was thrown from the car and under the wheels. Her neck was snapped, and she died almost instantly.

Mary Ward was the first person in the history of the world to die in a car accident.

She was a pioneer in many ways, but you don’t always get to choose what you’re a pioneer of. Today, around the world an estimated 1.3 million people die in car accidents every year. The future keeps on inconveniently arriving faster than we were expecting, and we keep struggling to predict it.

For example, in 1825, the Quarterly Review predicted that trains had no future. “What can be more palpably absurd than the prospect held out of locomotives traveling twice as fast as stagecoaches?” it asked.

A few years later, in 1830, William Huskisson, a British member of parliament and former minister of state, was attending the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. He was riding from Liverpool to Manchester in a train with the Duke of Wellington and numerous other dignitaries. Stopping off halfway for the engine to take on water, the passengers were instructed not to leave the carriages, but they did, anyway. Huskisson decided he should go and shake the Duke of Wellington’s hand, as they’d had a falling-out, which is why he was standing on the opposite line when George Stephenson’s famous Rocket was speeding past the other way. The passengers were warned to get out of the path of the oncoming train, but Huskisson, unfamiliar with the novel situation, panicked and couldn’t decide where to move. In the end, rather than simply standing with the other passengers on the far side of the line, he instead tried clambering up onto the carriage of Wellington’s train, only for the door he was desperately holding onto to swing open, putting him right in the path of the Rocket. And so William Huskisson was one of the first people in history to be killed by a train.

In 1871, Alfred Nobel said of his invention of dynamite: “Perhaps my factories will put an end to war sooner than your congresses: on the day that two army corps can mutually annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil with horror and disband their troops.”

In 1873, stock markets around the world crashed as a bubble of speculation finally burst. The global economic depression lasted for years.

In 1876, William Orton, the president of Western Union, advised a friend against investing in Alexander Graham Bell’s new invention—the telephone—by telling him: “There is nothing in this patent whatever, nor is there anything in the scheme itself, except as a toy.”

A few years after Nobel, in 1877, Richard Gatling, the inventor of the Gatling gun, wrote to a friend that he had hoped its invention would usher in a new, humanitarian era of warfare. He wrote how he was moved to invent it after he “witnessed almost daily the departure of troops to the front and the return of the wounded, sick, and dead… It occurred to me if I could invent a machine—a gun—which could, by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a great extent, supersede the necessity of large armies, and consequently, exposure to battle and disease be greatly diminished.”

In 1888, a Methodist missionary group in Chicago needed money and hit upon the idea of what they described as a “peripatetic contribution box”—they sent out 1,500 copies of a letter begging the recipients to send them a dime, and to forward a copy of the letter to three friends with the same request. They made over $6,000, though many people got very angry after receiving the letter multiple times. The chain letter had been born.

In 1897, the eminent British scientist Lord Kelvin predicted that “radio has no future.” Also in 1897, the New York Times praised Hiram Maxim’s invention of the fully automatic machine gun as being one so fearsome that it would stop wars from occurring, calling Maxim guns “peace-producing and peace-retaining terrors” that “because of their devastating effects, have made nations and rulers give greater thought to the outcome of war before entering upon projects of conquest.”

In 1902, Kelvin predicted in an interview that transatlantic flight was an impossibility, and that “no balloon and no airplane will ever be practically successful.” The Wright brothers flew their first flight 18 months later. As Orville Wright recalled in a letter from 1917: “When my brother and I built and flew the first man-carrying flying machine, we thought we were introducing into the world an invention which would make further wars practically impossible. That we were not alone in this thought is evidenced by the fact that the French Peace Society presented us with medals on account of our invention.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.