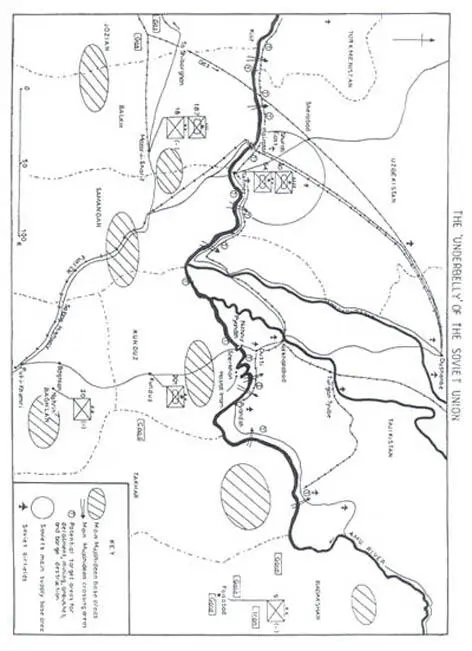

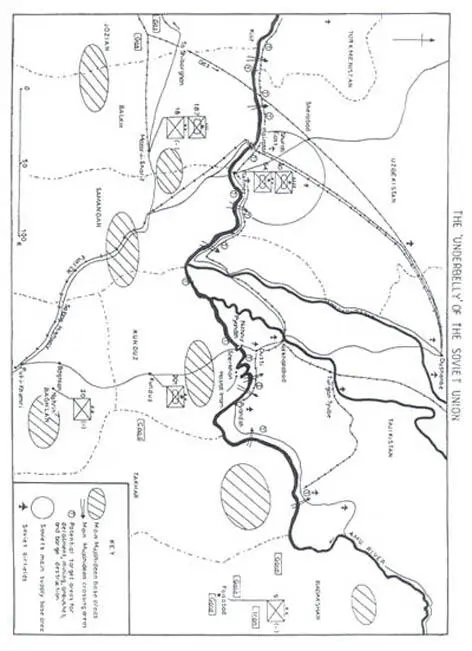

Into this melting pot of peoples, languages, cultures and Islam the Soviets had recently poured communism and quickly slammed the lid. The Army made sure it stayed shut. Casey had been right. It was an area of great potential for seriously damaging our enemy.

One of the men involved in our campaign of incursions over the Amu from the outset, indeed he later became the Commander of the raid that resulted in our being ordered to halt these operations, was Wali Beg. This is not his real name, as for obvious reasons it is essential for me to conceal his true identity. Wali Beg is an Uzbek, 53 years old but looks older, with a beard nearer to white than grey. He used to be a farmer and had a wife, two sons and a daughter. Now he has lost all his close family, and lives the life of a crippled carpet maker in a refugee camp in Pakistan. His original home was one of the tiny, long-since-destroyed villages on the south bank of the river in Kunduz Province. His house was only minutes walk from the water. It was also not far from the old Afghan river port of Sherkhan, which the Soviets had recently developed into a fuel storage area. A bridge now straddles the river at Sherkhan. This is a new structure, as trade and people had crossed the Amu for centuries in boats and barges at ferry crossing places. Wali remembers going over as a boy with his father to meet relatives and friends on the far side. Sometimes these people would visit his family. They would cross on flat-bottomed boats, towed by two swimming horses attached to outriggers. The horses were guided by the ferryman, and were partially supported in the water by the outriggers. By such means large loads of men and goods could be moved slowly across.

Wali’s background is typical of millions of Afghans. Islam had dominated his village life, with the mosque as the centre of all social organization. Only boys received any education, and that was in the mosque school, where Wali had learned to read a little, and learned a lot of verses and prayers from the Holy Koran. At the age of ten he became a herdsman and fed the animals. In rural Afghanistan every family, except the very poorest, has a few animals: a donkey, or preferably a horse, for transport, a cow for milking and calves, an ox to make up a yoke with neighbours, and a few goats or sheep. At fifteen he learned to plough.

Wali told me that his wife had been selected for him when she was still an infant. When she was fourteen they were married without his ever having seen her face, although relatives had told him she was pretty. Marriage was for the production of children. Most young women in those days expected to have a child every two years, although many died in infancy. Instances of one woman having sixteen children, of whom only five or six reached adulthood, are not unknown. Allah blessed Wali with four children, of whom two sons and a daughter lived.

Wali grew up beside the Amu, so over the years he acquired an extensive knowledge of his area. He knew the river, the tracks leading to it, the reed swamps that clogged its banks, and its twists and turns and tributary streams. He knew the strength of the current, he knew the river in flood, and in the winter when the water was at its lowest. He knew the little sandy islands that sometimes split the sluggish flow.

With the Soviet invasion Wali’s life was devastated. His sons had joined the Mujahideen, but the youngest, a boy of seventeen, was soon Shaheed in fighting along the Kunduz-Baghlan road. The eldest simply disappeared. To Wali this indicated arrest, infinitely worse than an honourable death in the Jehad. When I talked with Wali he was convinced his boy was dead, but it was the probable manner of his dying that consumed him. The tortures his son would have had to bear before death had released him made Wali’s hatred of the Soviets totally merciless. The bombing of his village while he was in Kunduz had killed his daughter, so he and his wife had fled to Pakistan via Chitral. Within a few months she had succumbed to malaria. For our purpose Wali’s knowledge of the border region, coupled with his oath of vengeance taken against the Soviets, made him an ideal Mujahid to carry the war over the Amu.

I had several options in attacking the Soviets in their own country. I could start with tentative incursions to distribute propaganda and to sound out how receptive the people would be to assisting with sabotage or other missions. Then I could confine our activities to firing into Soviet territory from inside Afghanistan, or sink barges and steamers on the river. Finally, I could send teams over the river to carry out rocket attacks, mine-laying, derailment of trains or ambushes. It was decided to start with the renewal of contacts, together with the distribution propaganda to test the water before anything more adventurous.

Casey had suggested sending books, and I had discussions on this with a CIA psychological warfare expert who recommended several books describing Soviet atrocities against Uzbeks. He was himself an Uzbek who had been working with the CIA since 1948. Although we agreed to use these books, our inclination was to send in copies of the Holy Koran that had been translated into Soviet Uzbek. We persuaded the CIA to obtain 10,000 copies.

While these were being printed we called in a number of Commanders and other suitable persons, including Wali, from the northern provinces. They were carefully screened, briefed to make contacts over the Amu and report back on whether the Holy Koran would be welcome, and whether some of the people would be willing to assist any future operations by giving information on Soviet troops movements, industrial installations, or act as guides. Later Wali explained to me how he had made his first trip in the late spring of 1984.

He decided to make for a village that he had last visited about ten years previously, as there was a good chance one or two of the families he knew would still be there. It was not safe to cross near Sherkhan, with its busy Soviet port of Nizhniy Pyandzh on the opposite bank, so he chose a quieter area where the river made several loops, and there were large expanses of jungle and reeds before reaching the bank. It would need to be a night crossing as he knew there were border security posts, and possibly patrols by day. Because of the distance he could not manhandle a boat, so it would mean swimming at least 600 metres, possibly more, as the Amu was full of icy water from melting snows. Wali had killed a goat, dried its skin and inflated it. He intended to cross as Alexander’s soldiers had done.

He had set off after dark carrying his goatskin. Within two hours he hit the reeds and swamp on the south bank, which slowed progress and were noisy. When he finally reached the river he could dimly see the land opposite only about 300 metres away. He was in luck—only a short swim. In fact he only had to swim for about half the distance, with the goatskin easily taking the weight of his body. The ground on the far side was flat and sandy, but after walking for some time he came to the river again. For a moment Wali had been perplexed, surely he had not walked in a circle. The channel in front of him was barely 100 metres across. Then it struck him; he had been on an island. Although he did not know it, the boundary between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union ran through the island, so he was now in hostile territory. Another short swim, followed by a two-hour walk brought him to the houses of the village he sought. The first grey streaks of dawn were on the horizon when Wali quietly dropped on his knees, bent forward to touch the sand with his forehead, offering his thanks to Allah for his mercy so far.

Wali spent two days in the village, much of the time out in the fields as a shepherd with his friends and their sheep. His report was entirely favourable. His contacts would welcome copies of the Holy Koran, and, yes, they would pass them on. Two men had asked for rifles, but Wali had not been able to agree to this at this stage. Perhaps later, if things developed well. weapons would follow, for the moment information on which to plan, and a willingness to provide guides or shelter was all that was needed.

Читать дальше