That evening back in Islamabad I received a telephone call from General Akhtar who wanted me to arrange to have the wreckage retrieved. He was dumbfounded when I explained that there was no plane and insisted I send an officer to check personally. I did, and he confirmed our version of the story, much to the embarrassment of the Pakistan Army. They had even sought to authenticate their claim by sending an officer to the Mujahideen to collect together some debris from another crashed aircraft, as evidence of their achievement. Fortunately better sense prevailed.

The US flew out a special team to find out why our Army could not get results with the Stinger. Senior Army officers refused to accept the numbers of Mujahideen kills as anything other than propaganda. When the President and General Akhtar insisted, they claimed they had been given a worthless, outdated version of the Stinger. I believe part of the reason was that the Pakistan Army did not use the weapon offensively; they did not set out to ambush aircraft, tempt them into vulnerable positions, before catching them by surprise. They were content to sit in a static defensive position and wait for a target to come their way, although to be fair that was really their only option in the circumstances on the frontier.

Early in 1987 I was informed that a PAF F16 had been shot down near Miram Shah, with the wreckage falling inside Afghanistan. The report alleged that it was the victim of a Stinger fired by the Mujahideen. There was a monumental rumpus. Everybody turned on the ISI with cries of, “I told you so. The Mujahideen should never have been given this weapon. They haven’t been trained properly. They can’t differentiate between Soviet and Pakistani aircraft.” I was sceptical from the start, as no Stinger team had either been deployed in that area or was moving through it. I informed General Akhtar accordingly, but rumours abounded, including one that the missile had been fired from inside Pakistan. The panic prevailed for 24 hours, until proper investigation revealed that the plane had been downed by another Pakistani fighter. There was acute embarrassment when it became known that it was the PAF, rather than the Mujahideen, who needed to brush up their aircraft recognition training.

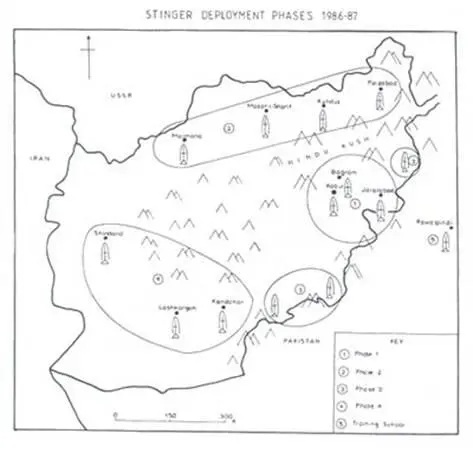

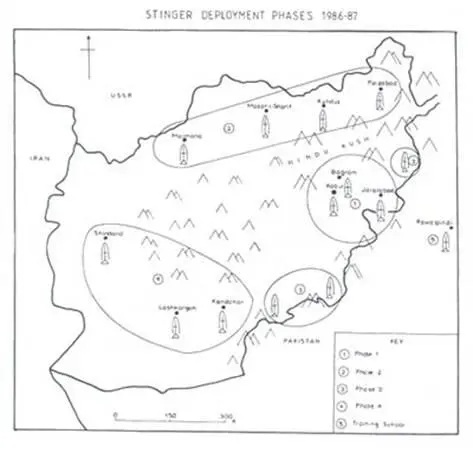

How best to deploy our wonder weapon was the subject of much animated discussion. As we could not suddenly flood Afghanistan with hundreds of Stingers, the strategic choice lay between concentrating first around enemy airfields, or deploying them close to the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, thus retaining a tighter control over the teams, and perhaps lessening the likelihood of one being captured. I argued strongly for the first option. I felt that the teams should be used boldly to strike offensively at important airfields. This was where our targets were concentrated. If we could achieve surprise, and hit hard at the outset, we would gain a tremendous moral advantage. To position them to protect our border bases would hand the initiative back to the enemy. All our American friends agreed, except for their Ambassador. He was fond of passing judgement on military matters about which he was imperfectly qualified to speak; this was such an occasion. He wanted the initial deployment around Barikot and Khost.

Military good sense prevailed (see Map 18). As previously narrated, the first Stingers achieved spectacular success at Jalalabad airfield. We also included Kabul—Bagram in phase one of their deployment. This was followed by sending them over the Hindu Kush to the airfields at Mazar-i-Sharif, Faisabad, Kunduz, Maimana and close to the Amu River. The third phase envisaged a more defensive role in the provinces bordering Pakistan, with the final deployment being around Kandahar and Lashkargah airfields. This area had a low priority because the terrain was so flat and arid that it favoured the enemy who, with the advantage of airpower, were able to spot Mujahideen movement with comparative ease.

The use of Stingers tipped the tactical balance in our favour. As success followed success, so the Mujahideen morale rose and that of the enemy fell. We now had the Soviet and Afghan pilots running scared; they were on the defensive. They became reluctant to fly low to push home attacks, while every transport aircraft at Kabul airport and elsewhere had its landing and take off protected by flare-dispersing helicopters. Even civil airliners, which we did not attack, adopted a tight corkscrew descent to the runway, causing much nervousness and vomiting by the passengers. We had instructed Commanders to hunt not only aircraft, but the crews as well. We wanted dead pilots more than dead planes, as the former were far harder to replace than the latter. We set out to kill or capture more pilots by training special ‘hit’ groups for this task, who accompanied each Stinger team whenever possible. We even went to the extent of targeting pilots’ messes at Kabul and Bagram for stand-off rocket attacks.

Although it was never our policy deliberately to kill captured aircrew, Soviet propaganda had instilled in many that to be taken prisoner was a fate infinitely worse than death. This had been the position long before we introduced Stingers. Back in 1984 the courageous British photographer John Gunston had captured this terrible fear in a photograph of a dead Soviet MiG-21 pilot, published in the French news weekly L’Expres. It showed the pilot lying amongst the shrouds of his collapsed parachute, still in his ejection seat with his hand cocked to his head. He had ejected, but had his leg ripped apart as his seat cleared the cockpit. On landing, in dreadful agony, he had shot himself through the brain to avoid capture. Later, the Mujahideen had removed the pistol from his hand. In his book Soldiers of God Robert Kaplan quotes Gunston as saying, “The pilot had been there for several weeks, and had turned black in the sun, though the snow had kept his body from decaying. Maggots were eating a hole in his face. I found his radio sigs and MiG-21 instruction book. But damn, the muj wouldn’t let me keep it.”

In 1987, in the Logar Valley, a Stinger missile downed a helicopter which burned like a furnace on impact with the ground. The Mujahideen raked through the debris, and filmed one guerrilla lifting up the tiny, shrivelled, blackened body of the pilot with the end of his stick. It looked like a grotesque charcoal doll.

In the ten-month period from the first firing up to when I left the ISI in August, 1987, 187 Stingers were used in Afghanistan. Of these 75 per cent hit aircraft. By this time every province, except for three, had them. Always we taught Commanders to plan and act offensively. They would put pressure on a post hoping that it would radio for assistance. If helicopters arrived they were ambushed. Similarly rocket attacks were used in broad daylight to tempt the Hinds into the sky. Sometimes they came, stayed high, fired a few rockets and disappeared. With high-flying helicopters the Mujahideen would often deliberately expose one or two vehicles, drive them so as to make a lot of dust, thereby hoping to entice the victim down. If he came he was usually killed. More often he stayed high.

There is no doubt that the introduction of Stingers caused considerable alarm among the enemy air crews. On one occasion two gunships were strafing a village when one was hit by a Stinger missile whereupon the pilot of the second helicopter bailed out in panic. The winter of 1986/87 was the first time that Commanders and Leaders were prepared to continue operating in strength throughout the severe weather. provided they had a good supply of Stingers. We exploited their enthusiasm to the maximum. It was the first winter in which we did not lose ground around Kabul; in fact some outposts were recaptured by the Mujahideen as the enemy gunships’ pilots were often too frightened to intervene effectively as before.

Читать дальше