The French Empire in Africa was established and defended by the sweat and blood of Senegalese, Algerians and working-class Frenchmen. The percentage of well-born Frenchmen within the ranks was negligible. Yet the percentage of well-born Frenchmen within the small elite that led the French army, ruled the empire and enjoyed its fruits was very high. Why just Frenchmen, and not French women?

In China there was a long tradition of subjugating the army to the civilian bureaucracy, so mandarins who had never held a sword often ran the wars. ‘You do not waste good iron to make nails,’ went a common Chinese saying, meaning that really talented people join the civil bureaucracy, not the army. Why, then, were all of these mandarins men?

One can’t reasonably argue that their physical weakness or low testosterone levels prevented women from being successful mandarins, generals and politicians. In order to manage a war, you surely need stamina, but not much physical strength or aggressiveness. Wars are not a pub brawl. They are very complex projects that require an extraordinary degree of organisation, cooperation and appeasement. The ability to maintain peace at home, acquire allies abroad, and understand what goes through the minds of other people (particularly your enemies) is usually the key to victory. Hence an aggressive brute is often the worst choice to run a war. Much better is a cooperative person who knows how to appease, how to manipulate and how to see things from different perspectives. This is the stuff empire-builders are made of. The militarily incompetent Augustus succeeded in establishing a stable imperial regime, achieving something that eluded both Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great, who were much better generals. Both his admiring contemporaries and modern historians often attribute this feat to his virtue of clementia – mildness and clemency.

Women are often stereotyped as better manipulators and appeasers than men, and are famed for their superior ability to see things from the perspective of others. If there’s any truth in these stereotypes, then women should have made excellent politicians and empire-builders, leaving the dirty work on the battlefields to testosterone-charged but simple-minded machos. Popular myths notwithstanding, this rarely happened in the real world. It is not at all clear why not.

Patriarchal Genes

A third type of biological explanation gives less importance to brute force and violence, and suggests that through millions of years of evolution, men and women evolved different survival and reproduction strategies. As men competed against each other for the opportunity to impregnate fertile women, an individual’s chances of reproduction depended above all on his ability to outperform and defeat other men. As time went by, the masculine genes that made it to the next generation were those belonging to the most ambitious, aggressive and competitive men.

A woman, on the other hand, had no problem finding a man willing to impregnate her. However, if she wanted her children to provide her with grandchildren, she needed to carry them in her womb for nine arduous months, and then nurture them for years. During that time she had fewer opportunities to obtain food, and required a lot of help. She needed a man. In order to ensure her own survival and the survival of her children, the woman had little choice but to agree to whatever conditions the man stipulated so that he would stick around and share some of the burden. As time went by, the feminine genes that made it to the next generation belonged to women who were submissive caretakers. Women who spent too much time fighting for power did not leave any of those powerful genes for future generations.

The result of these different survival strategies – so the theory goes – is that men have been programmed to be ambitious and competitive, and to excel in politics and business, whereas women have tended to move out of the way and dedicate their lives to raising children.

But this approach also seems to be belied by the empirical evidence. Particularly problematic is the assumption that women’s dependence on external help made them dependent on men, rather than on other women, and that male competitiveness made men socially dominant. There are many species of animals, such as elephants and bonobo chimpanzees, in which the dynamics between dependent females and competitive males results in a matriarchal society. Since females need external help, they are obliged to develop their social skills and learn how to cooperate and appease. They construct all-female social networks that help each member raise her children. Males, meanwhile, spend their time fighting and competing. Their social skills and social bonds remain underdeveloped. Bonobo and elephant societies are controlled by strong networks of cooperative females, while the self-centred and uncooperative males are pushed to the sidelines. Though bonobo females are weaker on average than the males, the females often gang up to beat males who overstep their limits.

If this is possible among bonobos and elephants, why not among Homo sapiens ? Sapiens are relatively weak animals, whose advantage rests in their ability to cooperate in large numbers. If so, we should expect that dependent women, even if they are dependent on men, would use their superior social skills to cooperate to outmanoeuvre and manipulate aggressive, autonomous and self-centred men.

How did it happen that in the one species whose success depends above all on cooperation, individuals who are supposedly less cooperative (men) control individuals who are supposedly more cooperative (women)? At present, we have no good answer. Maybe the common assumptions are just wrong. Maybe males of the species Homo sapiens are characterised not by physical strength, aggressiveness and competitiveness, but rather by superior social skills and a greater tendency to cooperate. We just don’t know.

What we do know, however, is that during the last century gender roles have undergone a tremendous revolution. More and more societies today not only give men and women equal legal status, political rights and economic opportunities, but also completely rethink their most basic conceptions of gender and sexuality. Though the gender gap is still significant, events have been moving at a breathtaking speed. At the beginning of the twentieth century the idea of giving voting rights to women was generally seen in the USA as outrageous; the prospect of a female cabinet secretary or Supreme Court justice was simply ridiculous; whereas homosexuality was such a taboo subject that it could not even be openly discussed. At the beginning of the twenty-first century women’s voting rights are taken for granted; female cabinet secretaries are hardly a cause for comment; and in 2013 five US Supreme Court justices, three of them women, decided in favour of legalising same-sex marriages (overruling the objections of four male justices).

These dramatic changes are precisely what makes the history of gender so bewildering. If, as is being demonstrated today so clearly, the patriarchal system has been based on unfounded myths rather than on biological facts, what accounts for the universality and stability of this system?

Part Three

The Unification of Humankind

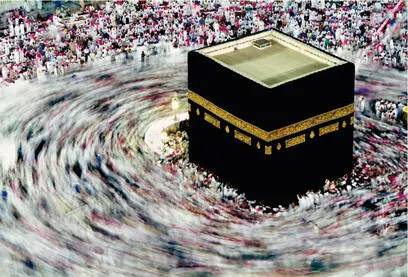

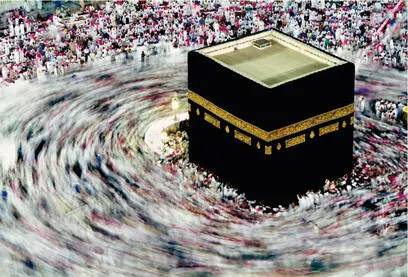

24. Pilgrims circling the Ka’aba in Mecca.

AFTER THE AGRICULTURAL REVOLUTION, human societies grew ever larger and more complex, while the imagined constructs sustaining the social order also became more elaborate. Myths and fictions accustomed people, nearly from the moment of birth, to think in certain ways, to behave in accordance with certain standards, to want certain things, and to observe certain rules. They thereby created artificial instincts that enabled millions of strangers to cooperate effectively. This network of artificial instincts is called culture’.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)