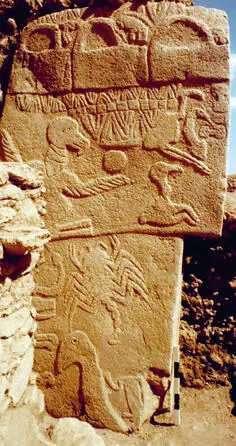

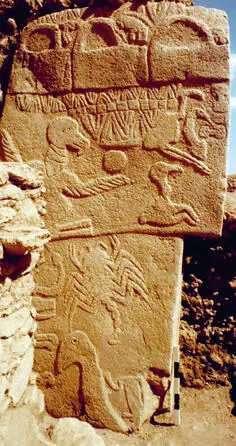

Yet, in some rare cases, we are lucky enough to find telltale clues. In 1995 archaeologists began to excavate a site in south-east Turkey called Göbekli Tepe. In the oldest stratum they discovered no signs of a settlement, houses or daily activities. They did, however, find monumental pillared structures decorated with spectacular engravings. Each stone pillar weighed up to seven tons and reached a height of five metres. In a nearby quarry they found a half-chiselled pillar weighing fifty tons. Altogether, they uncovered more than ten monumental structures, the largest of them nearly thirty metres across.

Archaeologists are familiar with such monumental structures from sites around the world – the best-known example is Stonehenge in Britain. Yet as they studied Göbekli Tepe, they discovered an amazing fact. Stonehenge dates to 2500 BC, and was built by a developed agricultural society. The structures at Göbekli Tepe are dated to about 9500 BC, and all available evidence indicates that they were built by hunter-gatherers. The archaeological community initially found it difficult to credit these findings, but one test after another confirmed both the early date of the structures and the pre-agricultural society of their builders. The capabilities of ancient foragers, and the complexity of their cultures, seem to be far more impressive than was previously suspected.

13. Opposite: The remains of a monumental structure from Göbekli Tepe. Right: One of the decorated stone pillars (about five metres high).

Why would a foraging society build such structures? They had no obvious utilitarian purpose. They were neither mammoth slaughterhouses nor places to shelter from rain or hide from lions. That leaves us with the theory that they were built for some mysterious cultural purpose that archaeologists have a hard time deciphering. Whatever it was, the foragers thought it worth a huge amount of effort and time. The only way to build Göbekli Tepe was for thousands of foragers belonging to different bands and tribes to cooperate over an extended period of time. Only a sophisticated religious or ideological system could sustain such efforts.

Göbekli Tepe held another sensational secret. For many years, geneticists have been tracing the origins of domesticated wheat. Recent discoveries indicate that at least one domesticated variant, einkorn wheat, originated in the Karaçadag Hills – about thirty kilometres from Göbekli Tepe. 6

This can hardly be a coincidence. It’s likely that the cultural centre of Göbekli Tepe was somehow connected to the initial domestication of wheat by humankind and of humankind by wheat. In order to feed the people who built and used the monumental structures, particularly large quantities of food were required. It may well be that foragers switched from gathering wild wheat to intense wheat cultivation, not to increase their normal food supply, but rather to support the building and running of a temple. In the conventional picture, pioneers first built a village, and when it prospered, they set up a temple in the middle. But Göbekli Tepe suggests that the temple may have been built first, and that a village later grew up around it.

Victims of the Revolution

The Faustian bargain between humans and grains was not the only deal our species made. Another deal was struck concerning the fate of animals such as sheep, goats, pigs and chickens. Nomadic bands that stalked wild sheep gradually altered the constitutions of the herds on which they preyed. This process probably began with selective hunting. Humans learned that it was to their advantage to hunt only adult rams and old or sick sheep. They spared fertile females and young lambs in order to safeguard the long-term vitality of the local herd. The second step might have been to actively defend the herd against predators, driving away lions, wolves and rival human bands. The band might next have corralled the herd into a narrow gorge in order to better control and defend it. Finally, people began to make a more careful selection among the sheep in order to tailor them to human needs. The most aggressive rams, those that showed the greatest resistance to human control, were slaughtered first. So were the skinniest and most inquisitive females. (Shepherds are not fond of sheep whose curiosity takes them far from the herd.) With each passing generation, the sheep became fatter, more submissive and less curious. Voilà ! Mary had a little lamb and everywhere that Mary went the lamb was sure to go.

Alternatively, hunters may have caught and adopted’ a lamb, fattening it during the months of plenty and slaughtering it in the leaner season. At some stage they began keeping a greater number of such lambs. Some of these reached puberty and began to procreate. The most aggressive and unruly lambs were first to the slaughter. The most submissive, most appealing lambs were allowed to live longer and procreate. The result was a herd of domesticated and submissive sheep.

Such domesticated animals – sheep, chickens, donkeys and others – supplied food (meat, milk, eggs), raw materials (skins, wool), and muscle power. Transportation, ploughing, grinding and other tasks, hitherto performed by human sinew, were increasingly carried out by animals. In most farming societies people focused on plant cultivation; raising animals was a secondary activity. But a new kind of society also appeared in some places, based primarily on the exploitation of animals: tribes of pastoralist herders.

As humans spread around the world, so did their domesticated animals. Ten thousand years ago, not more than a few million sheep, cattle, goats, boars and chickens lived in restricted Afro-Asian niches. Today the world contains about a billion sheep, a billion pigs, more than a billion cattle, and more than 25 billion chickens. And they are all over the globe. The domesticated chicken is the most widespread fowl ever. Following Homo sapiens , domesticated cattle, pigs and sheep are the second, third and fourth most widespread large mammals in the world. From a narrow evolutionary perspective, which measures success by the number of DNA copies, the Agricultural Revolution was a wonderful boon for chickens, cattle, pigs and sheep.

Unfortunately, the evolutionary perspective is an incomplete measure of success. It judges everything by the criteria of survival and reproduction, with no regard for individual suffering and happiness. Domesticated chickens and cattle may well be an evolutionary success story, but they are also among the most miserable creatures that ever lived. The domestication of animals was founded on a series of brutal practices that only became crueller with the passing of the centuries.

The natural lifespan of wild chickens is about seven to twelve years, and of cattle about twenty to twenty-five years. In the wild, most chickens and cattle died long before that, but they still had a fair chance of living for a respectable number of years. In contrast, the vast majority of domesticated chickens and cattle are slaughtered at the age of between a few weeks and a few months, because this has always been the optimal slaughtering age from an economic perspective. (Why keep feeding a cock for three years if it has already reached its maximum weight after three months?)

Egg-laying hens, dairy cows and draught animals are sometimes allowed to live for many years. But the price is subjugation to a way of life completely alien to their urges and desires. It’s reasonable to assume, for example, that bulls prefer to spend their days wandering over open prairies in the company of other bulls and cows rather than pulling carts and ploughshares under the yoke of a whip-wielding ape.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)