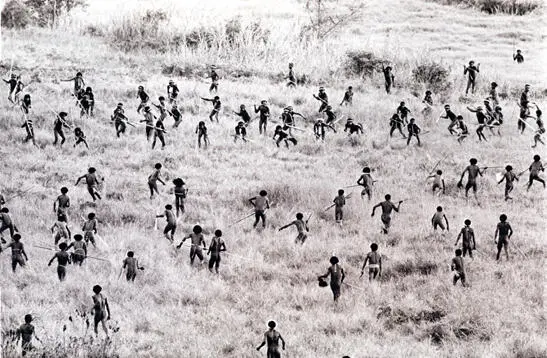

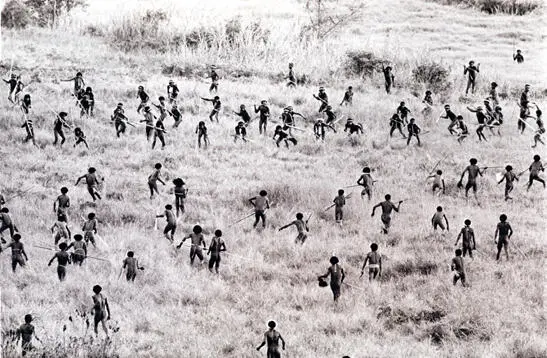

12. Tribal warfare in New Guinea between two farming communities (1960). Such scenes were probably widespread in the thousands of years following the Agricultural Revolution.

Many anthropological and archaeological studies indicate that in simple agricultural societies with no political frameworks beyond village and tribe, human violence was responsible for about 15 per cent of deaths, including 25 per cent of male deaths. In contemporary New Guinea, violence accounts for 30 per cent of male deaths in one agricultural tribal society, the Dani, and 35 per cent in another, the Enga. In Ecuador, perhaps 50 per cent of adult Waoranis meet a violent death at the hands of another human! 3In time, human violence was brought under control through the development of larger social frameworks – cities, kingdoms and states. But it took thousands of years to build such huge and effective political structures.

Village life certainly brought the first farmers some immediate benefits, such as better protection against wild animals, rain and cold. Yet for the average person, the disadvantages probably outweighed the advantages. This is hard for people in today’s prosperous societies to appreciate. Since we enjoy affluence and security, and since our affluence and security are built on foundations laid by the Agricultural Revolution, we assume that the Agricultural Revolution was a wonderful improvement. Yet it is wrong to judge thousands of years of history from the perspective of today. A much more representative viewpoint is that of a three-year-old girl dying from malnutrition in first-century China because her father’s crops have failed. Would she say ‘I am dying from malnutrition, but in 2,000 years, people will have plenty to eat and live in big air-conditioned houses, so my suffering is a worthwhile sacrifice’?

What then did wheat offer agriculturists, including that malnourished Chinese girl? It offered nothing for people as individuals. Yet it did bestow something on Homo sapiens as a species. Cultivating wheat provided much more food per unit of territory, and thereby enabled Homo sapiens to multiply exponentially. Around 13,000 BC, when people fed themselves by gathering wild plants and hunting wild animals, the area around the oasis of Jericho, in Palestine, could support at most one roaming band of about a hundred relatively healthy and well-nourished people. Around 8500 BC, when wild plants gave way to wheat fields, the oasis supported a large but cramped village of 1,000 people, who suffered far more from disease and malnourishment.

The currency of evolution is neither hunger nor pain, but rather copies of DNA helixes. Just as the economic success of a company is measured only by the number of dollars in its bank account, not by the happiness of its employees, so the evolutionary success of a species is measured by the number of copies of its DNA. If no more DNA copies remain, the species is extinct, just as a company without money is bankrupt. If a species boasts many DNA copies, it is a success, and the species flourishes. From such a perspective, 1,000 copies are always better than a hundred copies. This is the essence of the Agricultural Revolution: the ability to keep more people alive under worse conditions.

Yet why should individuals care about this evolutionary calculus? Why would any sane person lower his or her standard of living just to multiply the number of copies of the Homo sapiens genome? Nobody agreed to this deal: the Agricultural Revolution was a trap.

The Luxury Trap

The rise of farming was a very gradual affair spread over centuries and millennia. A band of Homo sapiens gathering mushrooms and nuts and hunting deer and rabbit did not all of a sudden settle in a permanent village, ploughing fields, sowing wheat and carrying water from the river. The change proceeded by stages, each of which involved just a small alteration in daily life.

Homo sapiens reached the Middle East around 70,000 years ago. For the next 50,000 years our ancestors flourished there without agriculture. The natural resources of the area were enough to support its human population. In times of plenty people had a few more children, and in times of need a few less. Humans, like many mammals, have hormonal and genetic mechanisms that help control procreation. In good times females reach puberty earlier, and their chances of getting pregnant are a bit higher. In bad times puberty is late and fertility decreases.

To these natural population controls were added cultural mechanisms. Babies and small children, who move slowly and demand much attention, were a burden on nomadic foragers. People tried to space their children three to four years apart. Women did so by nursing their children around the clock and until a late age (around-the-clock suckling significantly decreases the chances of getting pregnant). Other methods included full or partial sexual abstinence (backed perhaps by cultural taboos), abortions and occasionally infanticide. 4

During these long millennia people occasionally ate wheat grain, but this was a marginal part of their diet. About 18,000 years ago, the last ice age gave way to a period of global warming. As temperatures rose, so did rainfall. The new climate was ideal for Middle Eastern wheat and other cereals, which multiplied and spread. People began eating more wheat, and in exchange they inadvertently spread its growth. Since it was impossible to eat wild grains without first winnowing, grinding and cooking them, people who gathered these grains carried them back to their temporary campsites for processing. Wheat grains are small and numerous, so some of them inevitably fell on the way to the campsite and were lost. Over time, more and more wheat grew along favourite human trails and near campsites.

When humans burned down forests and thickets, this also helped wheat. Fire cleared away trees and shrubs, allowing wheat and other grasses to monopolise the sunlight, water and nutrients. Where wheat became particularly abundant, and game and other food sources were also plentiful, human bands could gradually give up their nomadic lifestyle and settle down in seasonal and even permanent camps.

At first they might have camped for four weeks during the harvest. A generation later, as wheat plants multiplied and spread, the harvest camp might have lasted for five weeks, then six, and finally it became a permanent village. Evidence of such settlements has been discovered throughout the Middle East, particularly in the Levant, where the Natufian culture flourished from 12,500 BC to 9500 BC. The Natufians were hunter-gatherers who subsisted on dozens of wild species, but they lived in permanent villages and devoted much of their time to the intensive gathering and processing of wild cereals. They built stone houses and granaries. They stored grain for times of need. They invented new tools such as stone scythes for harvesting wild wheat, and stone pestles and mortars to grind it.

In the years following 9500 BC, the descendants of the Natufians continued to gather and process cereals, but they also began to cultivate them in more and more elaborate ways. When gathering wild grains, they took care to lay aside part of the harvest to sow the fields next season. They discovered that they could achieve much better results by sowing the grains deep in the ground rather than haphazardly scattering them on the surface. So they began to hoe and plough. Gradually they also started to weed the fields, to guard them against parasites, and to water and fertilise them. As more effort was directed towards cereal cultivation, there was less time to gather and hunt wild species. The foragers became farmers.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)