While the interior of Roxelana’s rooms was visible only to her mentors, guests, and servants, she herself was an ambulatory messenger of her rank to all who might encounter her during the day. Her person required more elegant adornment, and so her wardrobe expanded. Roxelana’s new income would enable her to select fabrics for her gowns from the array of rare and expensive textiles produced around the empire and imported from abroad.

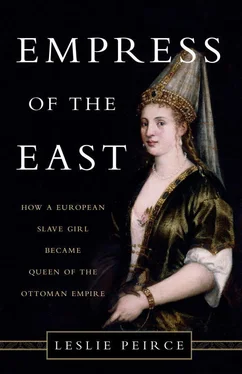

Headband and handkerchief belonging to Roxelana, preserved in her tomb.

Jewels came to Roxelana as congratulatory childbirth gifts. The most treasured of her ornaments almost certainly came from Suleyman. Every sultan cultivated a manual skill, and his was the art of goldsmithing. He had allegedly learned his craft from a Greek master in Trabzon, the city where he was born and educated. Known as Trebizond among the Byzantines, it was the last outpost of Greek civilization to fall to the Ottomans, in 1461. By 1526, the Venetian ambassador Pietro Bragadin could report that Suleyman had bestowed 100,000 ducats’ worth of jewels on his favorite. [5] Alberi, Relazioni , 3:102.

Even if rumor aggrandized the sum, the jewels were apparently a news item worthy of international note.

The daily routine of the young mother was now a busy one. Although much of Mehmed’s care was in the hands of his daye and his wet nurse, Roxelana was not deprived of opportunity for intimacy with her infant. A prince’s mother was to be his lifelong mentor. His father by contrast was frequently absent, either on military campaign or deep in council deliberations. Even when present in Istanbul, the sultan lived apart from his children. Angiolello underlined the parental responsibility of the concubine mother: “If she gives birth to a son, the boy is raised by his mother until the age of ten or eleven; then the Grand Turk gives him a province and sends his mother with him. …And if a girl is born, she is raised by her mother until the time she is married.” [6] Angiolello, Historia , 128.

By Suleyman’s day, the age at which princes and their mothers took up provincial service was rising—he himself had been fifteen when sent with Hafsa to Caffa. Mustafa would graduate to public life at eighteen and Mehmed at twenty.

As a new mother, possibly as young as seventeen, Roxelana needed guidance in the Ottoman approach to raising royal children. She could learn from Mehmed’s caregivers, who were available and also accountable if anything went wrong with the little boy’s development. If she had the opportunity to observe Mustafa and Mahidevran together, the senior concubine’s conduct could serve as a useful referent for the future—to emulate, improve upon, or perhaps disregard. Hafsa surely kept a grandmother’s eye on Mehmed and presumably asked her staff to monitor Roxelana’s well-being. At the same time, the culture of child raising in the Old Palace allowed a modicum of freedom for new mothers to follow the ways of their ancestors. After all, one reason for perpetuating the dynasty with slave concubines of varied origin was to exploit their very foreignness.

The nursery was not the only locus of Roxelana’s days. Her education continued and in fact accelerated. Her Turkish skills would advance, most likely with the help of a tutor, and her knowledge of Islam would deepen, perhaps with the guidance of a spiritually inclined palace elder. Improving her penmanship would free her from reliance on a harem scribe if she wanted to communicate privately. All of this activity, with its focus on the new little prince and the preparation of his mother as his future counselor, had another effect: it helped the concubine leave behind the intense interlude with the sultan who had gotten her pregnant. Her transformation required that she adjust her expectations and desires to her new destiny. Her gratification would now derive from her child and his successes.

UNEXPECTED THEN WAS Suleyman’s call for Roxelana to return to his bed. She conceived again sometime within four months of his return from Belgrade in October 1521. Suleyman was again away at war for most of Roxelana’s second pregnancy and also for the birth of their daughter Mihrumah in the fall of 1522. The following February, he returned to his capital with a stunning new victory: the capture of the Mediterranean island of Rhodes from the formidable crusader order of the Knights Hospitaller. Once again a conquest was paired with a new addition to the dynastic family. And once again, victory was followed by a return to the bedchamber with the concubine who had clearly become his favorite.

Over the next few years, Roxelana and Suleyman produced three more boys: Selim, Abdullah, and Bayezid. All were presumably planned, or at least welcome. Islamic law sanctioned forms of birth control, and the Old Palace had ways of dealing with unwanted conceptions. [7] For more on birth control, see Chapter 7.

No children were born to Suleyman with any other concubine during his entire reign. If he slept with any during his long absences from Istanbul or during Roxelana’s pregnancies, care was taken that no child issued from these encounters. Five children with one concubine in seven years and none with any other was a revolutionary break with tradition. An Ottoman sultan had become monogamous. What the consequences might be, no one could yet say.

Roxelana’s rise to favorite did not go unremarked. Public announcements of the royal births conveyed news of the couple’s fecundity and, by implication, the lovers’ presumed pleasures. Istanbulites may not have known the favorite’s name at first, but they could not escape a dawning awareness of the sultan’s maverick sexual habits. Venetian ambassadors, Europe’s keenest eyes and ears in Istanbul, tracked Suleyman’s growing attachment to Roxelana. In the space of a few years, the sultan’s amorous profile shifted in their reports from keen interest in his harem to constancy to one woman. Marco Minio had noted in 1522 that Suleyman was “very lustful,” but Pietro Zen, a longtime intimate of the Ottoman court, wrote to the Venetian Senate in 1524 that “the Seigneur is not lustful” and was devoted to a single woman. [8] Alberi, Relazioni , 3:78, 96.

By 1526, Pietro Bragadin could assert that the sultan no longer paid attention to the mother of his eldest son Mustafa, “a woman from Montenegro,” but gave all his affection to “another woman, of the Russian nation.” [9] Ibid., 3:102.

Although both Europeans and the Istanbul public were beginning to recognize Roxelana’s monopoly in the royal bedchamber, the old ways died hard in people’s minds. Even foreign observers appeared flummoxed by the idea of a monogamous sultan. Some fifteen years after Roxelana’s emergence as sole consort, Luigi Bassano was still relaying the standard story that sultans traded one concubine for another. [10] Bassano, Costumi , chap. 15.

The rumors that would later plague Roxelana—of her sorcery and Suleyman’s lovesickness—may well have germinated around this time, as people became aware of her seemingly permanent place in his life. The force of public opinion in the Ottoman capital was considerable, and Istanbulites had been known to censure their monarch when provoked.

For one thing, the public disapproved if the sultan appeared to overindulge in pleasure. His duty, they believed, was the defense of the empire from the several enemies threatening its borders. Even Mehmed the Conqueror had faced a challenge from his soldiers when he sent his grand vizier to command the army while he stayed home. When, in 1525, Janissaries in Istanbul rose up in protest against Suleyman’s prolonged absence—he had taken a long winter sojourn in Thrace to hunt—the rebels would pillage the customs house, the Jewish quarter where it was located, and the palaces of two viziers and the head treasurer. [11] Hammer, Histoire , 5:63.

One was the sumptuous residence of Ibrahim, Suleyman’s boon companion who was now grand vizier.

Читать дальше