This decree sheds interesting light on the French Revolution’s most famous document – The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – which recognised that all citizens have equal value and equal political rights. Is it a coincidence that universal rights were proclaimed at the same historical juncture that universal conscription was decreed? Though scholars may quibble about the exact relations between the two, in the following two centuries a common argument in defence of democracy explained that giving people political rights is good, because the soldiers and workers of democratic countries perform better than those of dictatorships. Allegedly, granting people political rights increases their motivation and their initiative, which is useful both on the battlefield and in the factory.

Thus Charles W. Eliot, president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, wrote on 5 August 1917 in the New York Times that ‘democratic armies fight better than armies aristocratically organised and autocratically governed’ and that ‘the armies of nations in which the mass of the people determine legislation, elect their public servants, and settle questions of peace and war, fight better than the armies of an autocrat who rules by right of birth and by commission from the Almighty’. 2

A similar rationale stood behind the enfranchisement of women in the wake of the First World War. Realising the vital role of women in total industrial wars, countries saw the need to give them political rights in peacetime. Thus in 1918 President Woodrow Wilson became a supporter of women’s suffrage, explaining to the US Senate that the First World War ‘could not have been fought, either by the other nations engaged or by America, if it had not been for the services of women – services rendered in every sphere – not only in the fields of effort in which we have been accustomed to see them work, but wherever men have worked and upon the very skirts and edges of the battle itself. We shall not only be distrusted but shall deserve to be distrusted if we do not enfranchise them with the fullest possible enfranchisement.’ 3

However, in the twenty-first century the majority of both men and women might lose their military and economic value. Gone is the mass conscription of the two world wars. The most advanced armies of the twenty-first century rely far more on cutting-edge technology. Instead of limitless cannon fodder, you now need only small numbers of highly trained soldiers, even smaller numbers of special forces super-warriors and a handful of experts who know how to produce and use sophisticated technology. Hi-tech forces ‘manned’ by pilotless drones and cyber-worms are replacing the mass armies of the twentieth century, and generals delegate more and more critical decisions to algorithms.

Aside from their unpredictability and their susceptibility to fear, hunger and fatigue, flesh-and-blood soldiers think and move on an increasingly irrelevant timescale. From the days of Nebuchadnezzar to those of Saddam Hussein, despite myriad technological improvements, war was waged on an organic timetable. Discussions lasted for hours, battles took days, and wars dragged on for years. Cyber-wars, however, may last just a few minutes. When a lieutenant on shift at cyber-command notices something odd is going on, she picks up the phone to call her superior, who immediately alerts the White House. Alas, by the time the president reaches for the red handset, the war has already been lost. Within seconds, a sufficiently sophisticated cyber strike might shut down the US power grid, wreck US flight control centres, cause numerous industrial accidents in nuclear plants and chemical installations, disrupt the police, army and intelligence communication networks – and wipe out financial records so that trillions of dollars simply vanish without trace and nobody knows who owns what. The only thing curbing public hysteria is that with the Internet, television and radio down, people will not be aware of the full magnitude of the disaster.

On a smaller scale, suppose two drones fight each other in the air. One drone cannot fire a shot without first receiving the go-ahead from a human operator in some bunker. The other drone is fully autonomous. Which do you think will prevail? If in 2093 the decrepit European Union sends its drones and cyborgs to snuff out a new French Revolution, the Paris Commune might press into service every available hacker, computer and smartphone, but it will have little use for most humans, except perhaps as human shields. It is telling that already today in many asymmetrical conflicts the majority of citizens are reduced to serving as human shields for advanced armaments.

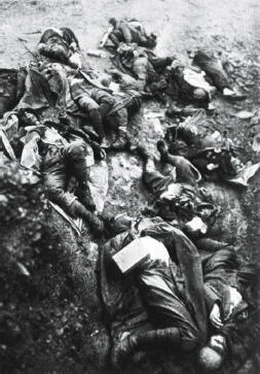

Left: Soldiers in action at the Battle of the Somme, 1916. Right: A pilotless drone.

Left: © Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images. Right: © alxpin/Getty Images.

Even if you care more about justice than victory, you should probably opt to replace your soldiers and pilots with autonomous robots and drones. Human soldiers murder, rape and pillage, and even when they try to behave themselves, they all too often kill civilians by mistake. Computers programmed with ethical algorithms could far more easily conform to the latest rulings of the international criminal court.

In the economic sphere too, the ability to hold a hammer or press a button is becoming less valuable than before. In the past, there were many things only humans could do. But now robots and computers are catching up, and may soon outperform humans in most tasks. True, computers function very differently from humans, and it seems unlikely that computers will become humanlike any time soon. In particular, it doesn’t seem that computers are about to gain consciousness, and to start experiencing emotions and sensations. Over the last decades there has been an immense advance in computer intelligence, but there has been exactly zero advance in computer consciousness. As far as we know, computers in 2016 are no more conscious than their prototypes in the 1950s. However, we are on the brink of a momentous revolution. Humans are in danger of losing their value, because intelligence is decoupling from consciousness.

Until today, high intelligence always went hand in hand with a developed consciousness. Only conscious beings could perform tasks that required a lot of intelligence, such as playing chess, driving cars, diagnosing diseases or identifying terrorists. However, we are now developing new types of non-conscious intelligence that can perform such tasks far better than humans. For all these tasks are based on pattern recognition, and non-conscious algorithms may soon excel human consciousness in recognising patterns. This raises a novel question: which of the two is really important, intelligence or consciousness? As long as they went hand in hand, debating their relative value was just a pastime for philosophers. But in the twenty-first century, this is becoming an urgent political and economic issue. And it is sobering to realise that, at least for armies and corporations, the answer is straightforward: intelligence is mandatory but consciousness is optional.

Armies and corporations cannot function without intelligent agents, but they don’t need consciousness and subjective experiences. The conscious experiences of a flesh-and-blood taxi driver are infinitely richer than those of a self-driving car, which feels absolutely nothing. The taxi driver can enjoy music while navigating the busy streets of Seoul. His mind may expand in awe as he looks up at the stars and contemplates the mysteries of the universe. His eyes may fill with tears of joy when he sees his baby girl taking her very first step. But the system doesn’t need all that from a taxi driver. All it really wants is to bring passengers from point A to point B as quickly, safely and cheaply as possible. And the autonomous car will soon be able to do that far better than a human driver, even though it cannot enjoy music or be awestruck by the magic of existence.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу