The same logic is at work in the economic sphere too. In 1999 the government of Scotland decided to erect a new parliament building. According to the original plan, the construction was supposed to take two years and cost £40 million. In fact, it took five years and cost £400 million. Every time the contractors encountered unexpected difficulties and expenses, they went to the Scottish government and asked for more time and money. Every time this happened, the government told itself: ‘Well, we’ve already sunk £40 million into this and we’ll be completely discredited if we stop now and end up with a half-built skeleton. Let’s authorise another £40 million.’ Six months later the same thing happened, by which time the pressure to avoid ending up with an unfinished building was even greater; and six months after that the story repeated itself, and so on until the actual cost was ten times the original estimate.

Not only governments fall into this trap. Business corporations often sink millions into failed enterprises, while private individuals cling to dysfunctional marriages and dead-end jobs. For the narrating self would much prefer to go on suffering in the future, just so it won’t have to admit that our past suffering was devoid of all meaning. Eventually, if we want to come clean about past mistakes, our narrating self must invent some twist in the plot that will infuse these mistakes with meaning. For example, a pacifist war veteran may tell himself, ‘Yes, I’ve lost my legs because of a mistake. But thanks to this mistake, I understand that war is hell, and from now onwards I will dedicate my life to fight for peace. So my injury did have some positive meaning: it taught me to value peace.’

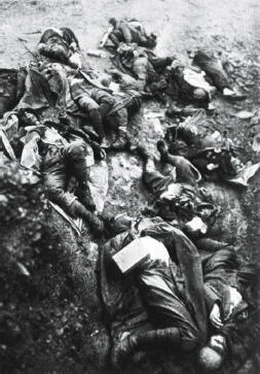

The Scottish Parliament building. Our sterling did not die in vain.

© Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Getty Images.

We see, then, that the self too is an imaginary story, just like nations, gods and money. Each of us has a sophisticated system that throws away most of our experiences, keeps only a few choice samples, mixes them up with bits from movies we saw, novels we read, speeches we heard, and from our own daydreams, and weaves out of all that jumble a seemingly coherent story about who I am, where I came from and where I am going. This story tells me what to love, whom to hate and what to do with myself. This story may even cause me to sacrifice my life, if that’s what the plot requires. We all have our genre. Some people live a tragedy, others inhabit a never-ending religious drama, some approach life as if it were an action film, and not a few act as if in a comedy. But in the end, they are all just stories.

What, then, is the meaning of life? Liberalism maintains that we shouldn’t expect an external entity to provide us with some readymade meaning. Rather, each individual voter, customer and viewer ought to use his or her free will in order to create meaning not just for his or her life, but for the entire universe.

The life sciences undermine liberalism, arguing that the free individual is just a fictional tale concocted by an assembly of biochemical algorithms. Every moment, the biochemical mechanisms of the brain create a flash of experience, which immediately disappears. Then more flashes appear and fade, appear and fade, in quick succession. These momentary experiences do not add up to any enduring essence. The narrating self tries to impose order on this chaos by spinning a never-ending story, in which every such experience has its place, and hence every experience has some lasting meaning. But, as convincing and tempting as it may be, this story is a fiction. Medieval crusaders believed that God and heaven provided their lives with meaning. Modern liberals believe that individual free choices provide life with meaning. They are all equally delusional.

Doubts about the existence of free will and individuals are nothing new, of course. Thinkers in India, China and Greece argued that ‘the individual self is an illusion’ more than 2,000 years ago. Yet such doubts don’t really change history unless they have a practical impact on economics, politics and day-to-day life. Humans are masters of cognitive dissonance, and we allow ourselves to believe one thing in the laboratory and an altogether different thing in the courthouse or in parliament. Just as Christianity didn’t disappear the day Darwin published On the Origin of Species , so liberalism won’t vanish just because scientists have reached the conclusion that there are no free individuals.

Indeed, even Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker and the other champions of the new scientific world view refuse to abandon liberalism. After dedicating hundreds of erudite pages to deconstructing the self and the freedom of will, they perform breathtaking intellectual somersaults that miraculously land them back in the eighteenth century, as if all the amazing discoveries of evolutionary biology and brain science have absolutely no bearing on the ethical and political ideas of Locke, Rousseau and Thomas Jefferson.

However, once the heretical scientific insights are translated into everyday technology, routine activities and economic structures, it will become increasingly difficult to sustain this double-game, and we – or our heirs – will probably require a brand-new package of religious beliefs and political institutions. At the beginning of the third millennium, liberalism is threatened not by the philosophical idea that ‘there are no free individuals’ but rather by concrete technologies. We are about to face a flood of extremely useful devices, tools and structures that make no allowance for the free will of individual humans. Can democracy, the free market and human rights survive this flood?

The preceding pages took us on a brief tour of recent scientific discoveries that undermine the liberal philosophy. It’s time to examine the practical implications of these scientific discoveries. Liberals uphold free markets and democratic elections because they believe that every human is a uniquely valuable individual, whose free choices are the ultimate source of authority. In the twenty-first century three practical developments might make this belief obsolete:

1. Humans will lose their economic and military usefulness, hence the economic and political system will stop attaching much value to them.

2. The system will still find value in humans collectively, but not in unique individuals.

3. The system will still find value in some unique individuals, but these will be a new elite of upgraded superhumans rather than the mass of the population.

Let’s examine all three threats in detail. The first – that technological developments will make humans economically and militarily useless – will not prove that liberalism is wrong on a philosophical level, but in practice it is hard to see how democracy, free markets and other liberal institutions can survive such a blow. After all, liberalism did not become the dominant ideology simply because its philosophical arguments were the most accurate. Rather, liberalism succeeded because there was much political, economic and military sense in ascribing value to every human being. On the mass battlefields of modern industrial wars, and in the mass production lines of modern industrial economies, every human counted. There was value to every pair of hands that could hold a rifle or pull a lever.

In 1793 the royal houses of Europe sent their armies to strangle the French Revolution in its cradle. The firebrands in Paris reacted by proclaiming the levée en masse and unleashing the first total war. On 23 August, the National Convention decreed that ‘From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old lint into linen; and the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic.’ 1

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу