During the preparations for OAF, NATO commanders ensured the availability of adequate CSAR forces. The size and nature of those forces reflected the specific combat circumstances. There are two crucial elements to CSAR success: a recovery vehicle to pick up the survivors and an on-scene commander (OSC) who locates the survivor, protects him or her if necessary, and directs the recovery vehicle to come forward when the area is safe. The recovery vehicle is usually a rescue or special forces helicopter, and the OSC is usually a specially trained A-10 pilot. However, other vehicles and pilots are capable of performing these functions, and there may be many other CSAR actors when the enemy threat is medium to high. These other elements could include the air-refueling tankers; a C-130 ABCCC to provide overall mission coordination and tracking of airborne assets; air-to-air fighters to provide air defense; F-16CJs and other similarly equipped aircraft to provide suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) and protection against enemy radar-guided surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems; jamming aircraft such as EA-6Bs; and any type of strike aircraft to provide air-to-ground firepower against enemy ground forces attempting to capture the survivors. These aircraft are often already in the target area performing their primary combat missions when the need arises, and they are then retasked to support the CSAR effort.

Another important element of the CSAR forces is the NATO airborne early warning (NAEW) aircraft, which provides radar coverage and directions to the tankers. The NAEW uses the E-3A aircraft, but its communications equipment is more limited than that of the USAF AWACS, and its aircrews are trained differently than US aircrews. These differences result in a lesser overall capability.

The specially trained and designated CSAR on-scene commanders have carried the Sandy call sign since the Vietnam War. Due to the difficulty and complexity of the mission, only the most experienced and capable A-10 pilots are selected to train as Sandys. They must stay cool and use exceptional judgment to find and talk to the survivor without giving away information to the enemy, who may also be listening or watching. The Sandy must have an extraordinary situational awareness to keep track of the survivor, numerous support aircraft, rescue helicopters, and enemy activity on the ground. An accurate synthesis of this information is absolutely critical to the success of the Sandy’s decision to commit to a helo pickup. Additionally, all CSAR participants must have unshakeable courage because their mission often means going deep into bad-guy land and exposure to significant ground and air threats.

In the Balkan theater the dedicated CSAR assets included MH-53J Pave Low helicopters from the 20th and 21st Special Operations Squadrons at Royal Air Force (RAF) Mildenhall, England. They had deployed regularly to Brindisi AB, Italy, since the mid-1990s. The A-10 Sandy aircraft were usually from the 81st FS/EFS (expeditionary fighter squadrons) from Spangdahlem AB, Germany, flying out of Aviano AB, and Gioia del Colle AB, Italy. During the years of routine deployments (from 1993 to 1999), these units flew CSAR exercises together in Bosnia with support from the NAEW and ABCCC but with little involvement with SEAD, air-to-air, or other attack aircraft. During this time, A-10 Sandys occasionally exercised with Italian and French forces using their Puma helicopters as recovery vehicles.

The first Kosovo crisis in October and November of 1998 led to the Spangdahlem Hogs being sent to Aviano to “stand up” a CSAR alert. At that time, the 81st pilots initiated the development of standardized CSAR procedures for the Balkan area by coordinating with personnel assigned to the CSAR cell at the combined air operations center (CAOC) in Vicenza, Italy, and representatives (rep) from the theater’s NAEW, ABCCC, and Pave Low communities. They renewed that process of coordination and cooperation during their return to Aviano in January, February, and March 1999. With the beginning of hostilities on 24 March, the 81st “stood up” a ground and airborne CSAR alert capability. With only a single two-hour exception on 11 April (during the 81st’s move from Aviano to Gioia del Colle), the 81st—along with the 74th FS and the 131st FS—maintained a continuous ground and/or airborne alert through-out the campaign. During the course of the air campaign, CSAR was 100 percent effective, successfully rescuing one F-117 pilot and one F-16CG pilot. Seven Hog drivers from the 81st and two from the 74th participated in those rescues—making crucial decisions at critical junctures, as well as ensuring that the pilots were picked up and that the helos made it in and out safely. Their personal accounts appear in subsequent chapters.

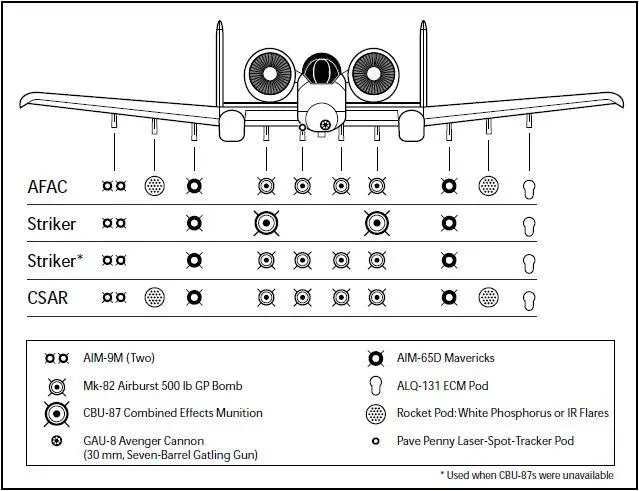

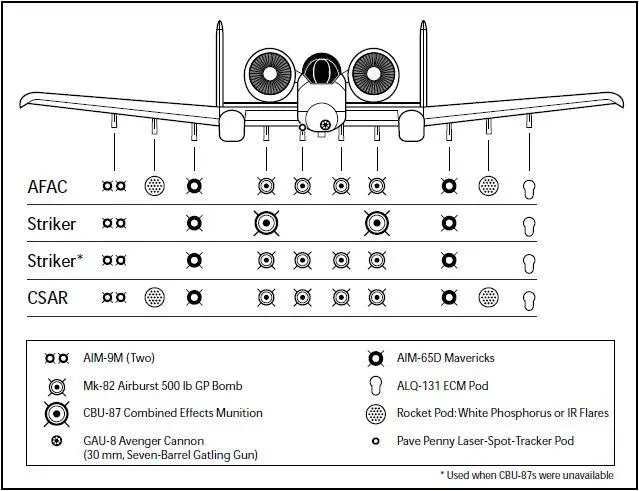

The Hog can carry a wide variety of weapons—and a bunch of them. On the in-flight mission cards Aviano planners listed the standard munitions load in a column labeled for each aircraft so the AFAC could quickly match the right weapon to the right target. These cards were distributed to all units involved in the Kosovo Engagement Zone (KEZ) and showed most aircraft as having one or two types of weapons available. Under the A-10 label, however, the column just reads, “Lots.”

Because the Hog has 11 suspension points for hanging weapons, missile rails, and electronic countermeasures, A-10 units in OAF could easily mix and match weapons based on day or night, AFAC, strike, or CSAR missions. The standard items for all A-10 missions included an AN/ALQ-131 electronic countermeasures pod; two AIM-9M Sidewinder heatseeking air-to-air missiles on a single dual-rail launcher; a Pave Penny laser-spot-tracker pod; a GAU-8 Avenger cannon (a 30 mm, seven-barrel Gatling gun) loaded with a combat mix of 1,150 depleted-uranium armor-piercing and high-explosive shells; and two AGM-65D Maverick missiles with imaging infrared (IIR) guidance and a large 125-pound (lb) cone-shaped-charge warhead. For day AFAC and CSAR alert sorties, the 81st loaded two pods of seven Willy Pete rockets for marking targets and two versatile Mk-82 “slick” 500 lb bombs with airburst radar fuses set to explode at about five meters above ground.

A-10 mission loads during OAF

These bombs did a great job of marking targets—even from 20,000 feet, any pilot could see a 500 lb bomb exploding, especially an airburst that made even more smoke than a groundburst. Airburst bombs were also more tactically viable against dug-in or soft, mobile targets. While slick, unguided bombs dropped by a Hog with no radar are fairly accurate, they are not precision weapons by any stretch of the imagination. An airburst gives the weapon a good chance of inflicting blast and shrapnel damage on the softer parts of an artillery piece inside an open revetment. A 500 lb bomb with a contact fuse that hits just one meter outside the target’s revetment is good only for making a lot of noise. After the first week of AFAC missions, the 81st decided to carry two additional airburst Mk-82 bombs. With only 1,000 lbs of extra weight and very little extra drag, they provided additional capability to attack targets when other fighters were not available.

Loading Mk-82 slicks on an A-10 (USAF Photo)

For night AFAC and CSAR missions, A-10 units replaced Willy Pete rockets with flare rockets that illuminated the target area for pilots wearing night vision goggles (NVG)—standard for all A-10 night operations. These rockets contained a canister that opened after launch and deployed a ground-illumination flare which then slowly descended by parachute and provided the Hog driver with up to three minutes of infrared (IR) illumination of ground targets and enemy activities.

Читать дальше