Of these procedures the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg that tried the major Nazi leadership between October 1945 and October 1946 is the best known, but there were many others: US, British and French military courts tried lower-level Nazis in their respective zones of occupied Germany and together with the Soviet Union they delivered Nazis to other countries—notably Poland and France—for trial in the places where their crimes had been committed. The programme of War Crimes Trials continued throughout the Allied occupation of Germany: in the Western zones more than 5,000 people were convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity, of whom just under 800 were condemned to death and 486 eventually executed—the last of these in Landsberg prison in June 1951 over vociferous German appeals for clemency.

There could hardly be a question of punishing Germans merely for being Nazis, despite the Nuremberg finding that the Nazi Party was a criminal organization. The numbers were too great and the arguments against collective guilt too compelling. In any case, it was not clear what could follow from finding many millions of people guilty in this way. The responsibilities of the Nazi leaders were clear, however, and there was never any doubt about their likely fate. In the words of Telford Taylor, one of the US prosecutors at Nuremberg and Chief Prosecutor at subsequent trials: ‘Too many people believed they had been wrongfully hurt by the leaders of the Third Reich and wanted a judgment to that effect.’

From the outset the German War Crimes trials were as much about pedagogy as justice. The main Nuremberg Trial was broadcast twice daily on German radio, and the evidence it amassed would be deployed in schools, cinemas and re-education centers throughout the country. However, the exemplary benefits of trials were not always self-evident. In an early series of trials of concentration camp commanders and guards, many escaped punishment altogether. Their lawyers exploited the Anglo-American system of adversarial justice to their advantage, cross-examining and humiliating witnesses and camp survivors. At the Lüneberg trial of the staff of Bergen-Belsen (September 17th-November 17th 1945), it was British defence lawyers who argued with some success that their clients had only been obeying (Nazi) laws: 15 of the 45 defendants were acquitted.

It is thus hard to know how far the trials of Nazis contributed to the political and moral re-education of Germany and the Germans. They were certainly resented by many as ‘victors’ justice’, and that is just what they were. But they were also real trials of real criminals for demonstrably criminal behaviour and they set a vital precedent for international jurisprudence in decades to come. The trials and investigations of the years 1945-48 (when the UN War Crimes Commission was disbanded) put an extraordinary amount of documentation and testimony on record (notably concerning the German project to exterminate Europe’s Jews), at the very moment when Germans and others were most disposed to forget as fast as they could. They made clear that crimes committed by individuals for ideological or state purposes were nonetheless the responsibility of individuals and punishable under law. Following orders was not a defense.

There were, however, two unavoidable shortcomings to the Allied punishment of German war criminals. The presence of Soviet prosecutors and Soviet judges was interpreted by many commentators from Germany and Eastern Europe as evidence of hypocrisy. The behaviour of the Red Army, and Soviet practice in the lands it had ‘liberated’, were no secret—indeed, they were perhaps better known and publicized then than in later years. And the purges and massacres of the 1930s were still fresh in many people’s memory. To have the Soviets sitting in judgment on the Nazis—sometimes for crimes they had themselves committed—devalued the Nuremberg and other trials and made them seem exclusively an exercise in anti-German vengeance. In the words of George Kennan: ‘The only implication this procedure could convey was, after all, that such crimes were justifiable and forgivable when committed by the leaders of one government, under one set of circumstances, but unjustifiable and unforgivable, and to be punished by death, when committed by another government under another set of circumstances.’

The Soviet presence at Nuremberg was the price paid for the wartime alliance and for the Red Army’s pre-eminent role in Hitler’s defeat. But the second shortcoming of the trials was inherent in the very nature of judicial process. Precisely because the personal guilt of the Nazi leadership, beginning with Hitler himself, was so fully and carefully established, many Germans felt licensed to believe that the rest of the nation was innocent, that Germans in the collective were as much passive victims of Nazism as anyone else. The crimes of the Nazis might have been ‘committed in the name of Germany’ (to quote the former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, speaking half a century later), but there was little genuine appreciation that they had been perpetrated by Germans.

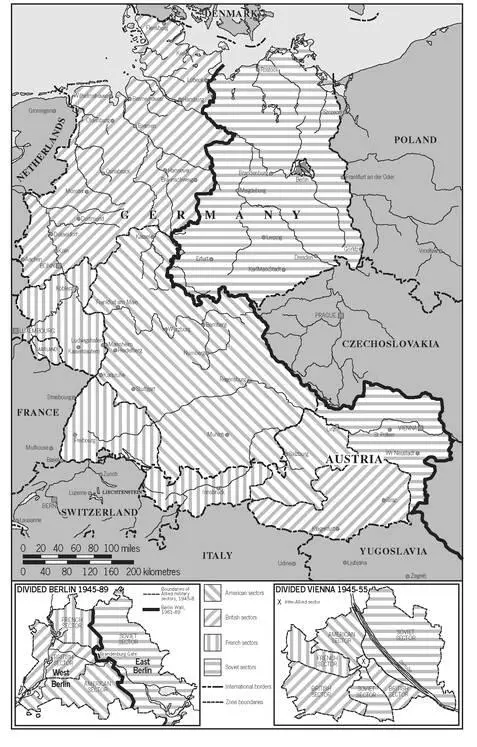

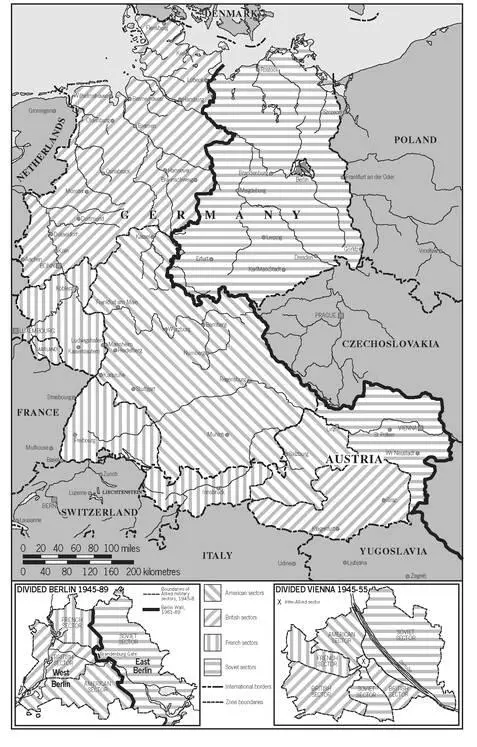

Germany and Austria: Allied Occupation Sectors

The Americans in particular were well aware of this and immediately initiated a programme of re-education and denazification in their zone, whose objective was to abolish the Nazi Party, tear up its roots and plant the seeds of democracy and liberty in German public life. The US Army in Germany was accompanied by a host of psychologists and other specialists, whose assigned task was to discover just why the Germans had strayed so far. The British undertook similar projects, though with greater skepticism and fewer resources. The French showed very little interest in the matter. The Soviets, on the other hand, were initially in full agreement and aggressive denazification measures were one of the few issues on which the Allied Occupation authorities could agree, at least for a while.

The real problem with any consistent programme aimed at rooting out Nazism from German life was that it was simply not practicable in the circumstances of 1945. In the words of General Lucius Clay, the American Military Commander, ‘our major administrative problem was to find reasonably competent Germans who had not been affiliated or associated in some way with the Nazi regime… All too often, it seems that the only men with the qualifications… are the career civil servants… a great proportion of whom were more than nominal participants (by our definition) in the activities of the Nazi Party.’

Clay did not exaggerate. On May 8th 1945, when the war in Europe ended, there were 8 million Nazis in Germany. In Bonn, 102 out of 112 doctors were or had been Party members. In the shattered city of Cologne, of the 21 specialists in the city waterworks office—whose skills were vital for the reconstruction of water and sewage systems and in the prevention of disease—18 had been Nazis. Civil administration, public health, urban reconstruction and private enterprise in post-war Germany would inevitably be undertaken by men like this, albeit under Allied supervision. There could be no question of simply expunging them from German affairs.

Nevertheless, efforts were made. Sixteen million Fragebogen (questionnaires) were completed in the three western zones of occupied Germany, most of them in the area under American control. There, the US authorities listed 3.5 million Germans (about one quarter of the total population of the zone) as ‘chargeable cases’, though many of them were never brought before the local denazification tribunals, set up in March 1946 under German responsibility but with Allied oversight. German civilians were taken on obligatory visits to concentration camps and made to watch films documenting Nazi atrocities. Nazi teachers were removed, libraries restocked, newsprint and paper supplies taken under direct Allied control and re-assigned to new owners and editors with genuine anti-Nazi credentials.

Читать дальше