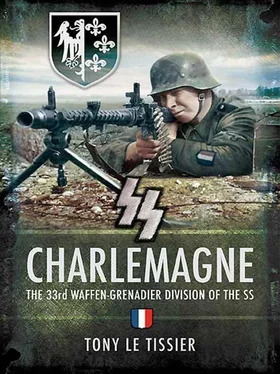

Tony Le Tissier

SS-CHARLEMAGNE

THE 33rd WAFFEN-GRENADIER DIVISION OF THE SS

1. Action

2. Withdrawal

3. Retreat

4. Gotenhafen

5. The Southern Suburbs

6. Berlin–Neukölln

7. Berlin–Mitte

8. Mecklenburg

1. The LVF marching down Les Champs-Elysees.

2. The LVF parading at Les Invalides.

3. The highly decorated RSM of the LVF.

4. A recruiting poster for the Charlemagne .

5. SS-Major-General Dr Gustav Krukenberg.

6. Colonel/Brigadier Edgar Puaud.

7. SS-Colonel Walter Zimmermann.

8. Roman Catholic Padre Count Jean de Mayol de Lupé.

9. Major Jean de Vaugelas.

10. Major Paul-Marie Gamory-Dubourdeau.

11. Major Eugène Bridoux.

12. Captain Emile Monneuse.

13. Captain Victor de Bourmont.

14. Major Boudet-Gheusi.

15. Captain Henri Josef Fenet.

16. Captain René-André Obitz.

17. Captain Jean Bassompierre.

18. Captain Berrier.

19. 2/Lt Jean Labourdette.

20. Sergeant-Major Croiseille.

21. Lieutenant Pierre Michel.

22. Sergeant-Major Pierre Rostaing.

23. 2/Lt Roger Albert-Brunet.

24. Officer-Cadet Protopopoff.

25. Staff-Sergeant Ollivier.

26. Sergeant Eugène Vaulot.

27. SS-Captain Wilhelm Weber.

28. The Waffen-SS leadership academy at Bad Tölz.

29. Field conditions in Pomerania.

30. Field conditions in Pomerania.

31. The evacuation of Kolberg.

32. Lieutenant Fenet manning a machine gun.

33. The double gates to Hitler’s Chancellery.

34. Devastation on Friedrichstrasse.

35. The U-Bahn entrance at the Kaiserhof Hotel.

36. Potsdamerstrasse.

37. Corporal Robert Soulat.

38. General Phillipe Leclerk examining the thirteen Charlemagne prisoners handed over to him.

On VE Day, 8 May 1945, a firing squad from General Leclerk’s 2nd Armoured Division summarily executed twelve prisoners from the Depot Battalion of the 33rd Waffen-Grenadier-Division of the SS-Charlemagne as traitors in a woodland clearing near the village of Karlstein in southeastern Bavaria. These prisoners had been part of a batch taken in the area by American troops and handed over to the Free French forces as they moved on.

If nothing else, this incident brought home the consequences of collaboration with the Germans during their occupation of France and the complications of interpreting and assessing such matters in relation to the prevailing political situation. The subject remains open for debate.

This book is mainly based upon material collated and most generously provided by Monsieur Robert Soulat, a former member of the Charlemagne , whose experience as a corporal clerk in the organisation provided the incentive. I was reluctant at first to undertake the task of writing up this story, as it involves such a complicated and sensitive era in French history, but in the end I could not let this interesting material go to waste.

In the spring of 1944 a new OKW general order foresaw the transfer of all foreign soldiers serving in the German Army to the Waffen-SS in order to simplify and improve their organisation. The assassination attempt against Hitler of 20 July 1944 accelerated this transfer, and particularly that of the French volunteers, who found themselves among the last involved in this reorganisation. Further, the two principal organisations concerned, the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF) and the French Storm Brigade of the Waffen-SS, were then both currently engaged on the Eastern Front, where the situation was becoming increasingly critical.

Under Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler’s pseudo-mystic leadership, the greatly expanded wartime Waffen-SS was considered to consist of three categories of personnel, German, Germanic and non-Germanic, the French fitting into the latter category. This classification was also reflected in formation titles, with ‘volunteer’ used in Germanic formation titles and non-Germanic titles being styled ‘Waffen-Division der SS’. However, the title of ‘Division’ did not necessarily mean that it met that establishment in either numbers or equipment.

Though eventful, the life of the Charlemagne as a brigade, division and finally battalion from August 1944 to May 1945 was brief. Uniformed, equipped, trained and commanded as a Waffen-SS unit, its members were listed with SS ranks bearing the Waffen prefix, i.e. W-Obersturmmführer (lieutenant) as opposed to SS-Obersturmführer . I have therefore translated all ranks into their British equivalents and only used the SS prefix for German Waffen-SS personnel. Also, although the rank of SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Waffen-SS actually equated to Brigadier in the British Army, I have used SS-Major-General in my translation, to allow the insertion of the intermediate rank of Oberführer , peculiar to the Waffen-SS, as Brigadier.

We should be under no illusions as to what kind of people enlisted in or were compulsorily transferred into the Charlemagne . As we shall see, there may have been some honest political motivation among the original members of the Légion des Volontaires Français of 1941, but the Miliciens who swelled the ranks in 1944 were essentially fugitives from the wrath of their now mainly Gaullist or Communist compatriots, who considered them as both outcasts and renegades.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that no war crimes could later be attributed to the Charlemagne . It fought both bravely and well.

The crushing military defeat of France in 1940 arose out of many factors, but principally out of the devastating results of the First World War of 1914–1918, from which the country had yet to recover. The country’s faith in the defences of the Maginot Line had been shattered when the German blitzkrieg smashed through between the French mobile forces covering the still open northern flank and the Maginot Line itself. Poor military leadership and lack of political willpower led to a swift disintegration of the state and humiliating surrender.

Following the signing of the armistice at Compiègne on the 22 June 1940, the new French government, headed by Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain with Pierre Laval as Deputy Premier, settled in the town of Vichy. France was now divided into occupied and unoccupied zones, but the coastal and border areas became restricted zones, while the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine were absorbed into the Third Reich, coming under the German conscription laws, as did the Duchy of Luxembourg, and the conscripts from these areas were deliberately deployed away from their home territory.

With the population stunned by the crushing defeat of French arms and the German invasion, Pétain and Laval sought to set aside the political turmoil of the inter-war years under the Third Republic by reviving morale with what they dubbed a National Revolution devoted to ‘Work, Family and Country’.

On 11 October 1940, Pétain broadcast a speech to the nation in which he alluded to the possibility of France and Germany working together once peace had been established in Europe, using the word ‘collaboration’ in this context. In any case, with 1,700,000 French servicemen in German prisoner-of-war camps, his government had little alternative but to comply.

The Germans, on the other hand, were out to avenge their own humiliation at Versailles at the end of the previous war, and had no real interest in establishing a sympathetic ally or even an independent fascist state in France. In its relationship with France, all other concerns were subordinate to German interests.

Читать дальше