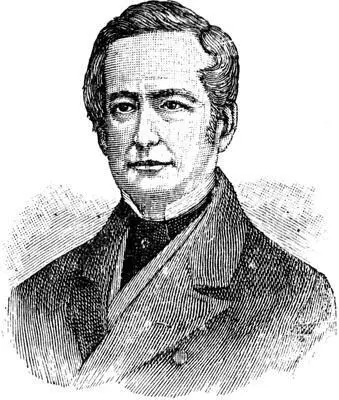

Captain Charles Sturt.

4. Captain Sturt.—The long drought which occurred between 1826 and 1828 suggested to Governor Darling the idea that, as the swamps which had impeded Oxley’s progress would be then dried up, the exploration of the river Macquarie would not present the same difficulties as formerly. The charge of organising an expedition was given to Captain Sturt, who was to be accompanied by Hume, with a party of two soldiers and eight convicts. They carried with them portable boats; but when they reached the Macquarie they found its waters so low as to be incapable of floating them properly. Trudging on foot along the banks of the river they reached the place where Oxley had turned back. It was no longer a marsh; but, with the intense heat, the clay beneath their feet was baked and hard; there was the same dreary stretch of reeds, now withered and yellow under the glare of the sun. Sturt endeavoured to penetrate this solitude, but the physical exertion of pushing their way through the reeds was too great for them. If they paused to rest, they were almost suffocated in the hot and pestilent air; the only sound they could hear was the distant booming of the bittern, and a feeling of the most lonely wretchedness pervaded the scene. At length they were glad to leave this dismal region and strike to the west through a flat and monotonous district where the shells and claws of crayfish told of frequent inundations. Through this plain there flowed a river, which Sturt called the Darling, in honour of the Governor. They followed this river for about ninety miles, and then took their way back to Sydney, Sturt being now able to prove that the belief in the existence of a great inland sea was erroneous.

5. The Murray.—In 1829, along with a naturalist named Macleay, Sturt was again sent out to explore the interior, and on this occasion carried his portable boats to the Murrumbidgee, on which he embarked his party of eight convicts. They rowed with a will, and soon took the boat down the river beyond its junction with the Lachlan. The stream then became narrow, a thick growth of overhanging trees shut out the light from above, while, beneath, the rushing waters bore them swiftly over dangerous snags and through whirling rapids, until they were suddenly shot out into the broad surface of a noble stream which flowed gently over its smooth bed of sand and pebbles. This river they called the Murray; but it was afterwards found to be only the lower portion of the stream which had been crossed by Hume and Hovell several years before.

Sturt’s manner of journeying was to row from sunrise to sunset, then land on the banks of the river and encamp for the night. This exposed the party to some dangers from the suspicious natives, who often mustered in crowds of several hundreds; but Sturt’s kindly manner and pleasant smile always converted them into friends, so that the worst mishap he had to record was the loss of his frying-pan and other utensils, together with some provisions, which were stolen by the blacks in the dead of night. After twilight the little encampment was often swarming with dark figures; but Sturt joined in their sports, and Macleay especially became a great favourite with them by singing comic songs, at which the dusky crowds roared with laughter. The natives are generally good-humoured, if properly managed; and throughout Sturt’s trip the white men and the blacks contrived to spend a very friendly and sociable time together.

After following the Murray for about two hundred miles below the Lachlan they reached a place where a large river flowed from the north into the Murray. This was the mouth of the river Darling, which Sturt himself had previously discovered and named. He now turned his boat into it, in order to examine it for a short distance; but after they had rowed a mile or two they came to a fence of stakes, which the natives had stretched across the river for the purpose of catching fish. Rather than break the fence, and so destroy the labours of the blacks, Sturt turned to sail back. The natives had been concealed on the shore to watch the motions of the white men, and seeing their considerate conduct, they came forth upon the bank and gave a loud shout of satisfaction. The party in the boat unfurled the British flag, and answered with three hearty cheers, as they slowly drifted down with the current. This humane disposition was characteristic of Captain Sturt, who, in after life, was able to say that he had never—either directly or indirectly—caused the death of a black fellow.

When they again entered on the Murray they were carried gently by the current—first to the west, then to the south; and, as they went onward, they found the river grow deeper and wider, until it spread into a broad sheet of water, which they called Lake Alexandrina, after the name of our present Queen, who was then the Princess Alexandrina Victoria. On crossing this lake they found the passage to the ocean blocked up by a great bar of sand, and were forced to turn their boat round and face the current, with the prospect of a toilsome journey of a thousand miles before they could reach home. They had to work hard at their oars, Sturt taking his turn like the rest. At length they entered the Murrumbidgee; but their food was now failing, and the labour of pulling against the stream was proving too great for the men, whose limbs began to grow feeble and emaciated. Day by day they struggled on, swinging more and more wearily at their oars, their eyes glassy and sunken with hunger and toil, and their minds beginning to wander as the intense heat of the midsummer sun struck on their heads. One man became insane; the others frequently lay down, declaring that they could not row another stroke, and were quite willing to die. Sturt animated them, and, with enormous exertions, he succeeded in bringing the party to the settled districts, where they were safe. They had made known the greatest river of Australia and traversed one thousand miles of unknown country, so that this expedition was by far the most important that had yet been made into the interior; and Sturt, by land, with Flinders, by sea, stands first on the roll of Australian discoverers.

6. Mitchell.—The next traveller who sought to fill up the blank map of Australia was Major Mitchell. Having offered, in 1831, to conduct an expedition to the north-west, he set out with fifteen convicts and reached the Upper Darling; but two of his men, who had been left behind to bring up provisions, were speared by the blacks, and the stores plundered. This disaster forced the company soon after to return. In 1835, when the major renewed his search, he was again unfortunate. The botanist of the party, Richard Cunningham, brother of the Allan Cunningham already mentioned, was treacherously killed by the natives; and, finally, the determined hostility of the blacks brought the expedition to an ignominious close.

In 1836 Major Mitchell undertook an expedition to the south, and in this he was much more successful. Taking with him a party of twenty-five convicts, he followed the Lachlan to its junction with the Murrumbidgee. Here he stayed for a short time to explore the neighbouring country; but the party was attacked by hordes of natives, some of whom were shot. The major then crossed the Murray; and, from a mountain top in the Lodden district, he looked forth on a land which he declared to be like the Garden of Eden. On all sides rich expanses of woodland and grassy plains stretched away to the horizon, watered by abundant streams. They then passed along the slopes of the Grampians and discovered the river Glenelg, on which they embarked in the boats which they had carried with them. The scenery along this stream was magnificent; luxurious festoons of creepers hung from the banks, trailing downwards in the eddying current, and partly concealing the most lovely grottos which the current had wrought out of the pure white banks of limestone. The river wound round abrupt hills and through verdant valleys, which made the latter part of their journey to the sea most agreeable and refreshing. Being stopped by the bar at the mouth of the Glenelg, they followed the shore for a short distance eastward, and then turned towards home. Portland Bay now lay on their right, and Mitchell made an excursion to explore it. What was his surprise to see a neat cottage on the shore, with a small schooner in front of it at anchor in the bay. This was the lonely dwelling of the brothers Henty, who had crossed from Tasmania and founded a whaling station at Portland Bay. On Mitchell’s return he had a glorious view from the summit of Mount Macedon, and what he saw induced him, on his return to Sydney, to give to the country the name “Australia Felix”. As a reward for his important services he received a vote of one thousand pounds from the Council at Sydney, and he was shortly afterwards knighted; so that he is now known as Sir Thomas Mitchell.

Читать дальше