7. Governor Bourke.—Sir Richard Bourke, who succeeded him, was the most able and the most popular of all the Sydney Governors. He had the talent and energy of Macquarie; but he had, in addition, a frank and hearty manner, which insensibly won the hearts of the colonists, who, for years after his departure, used to talk affectionately of him as the “good old Governor Bourke”. During his term of office the colony continued in a sober way to make steady progress. In 1833 its population numbered 60,000, of whom 36,000 were free persons. Every year there arrived three thousand fresh convicts; but as an equal number of free immigrants also arrived, the colony was benefited by its annual increase of population.

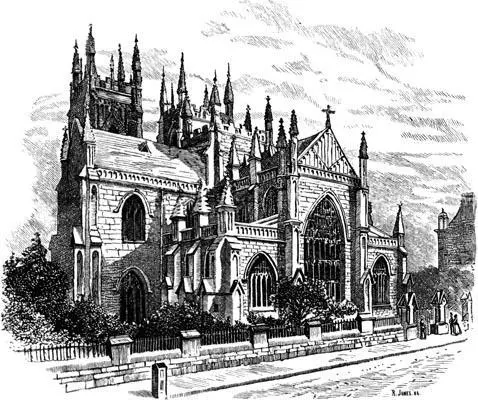

St. Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney.

8. The Land Question.—Governor Bourke, on his landing, found that much discontent existed with reference to what was called the Land Question. It was understood that any one who applied for land to the Government, and showed that he would make a good use of it, would receive a suitable area as a free grant. But many abuses crept in under this system. In theory, all men had an equal right to obtain the land they required; but, in practice, it was seldom possible for one who had no friends among the officials at Sydney to obtain a grant. An immigrant had often to wait for months, and see his application unheeded; while, meantime, a few favoured individuals were calling day by day at the Land Office, and receiving grant after grant of the choicest parts of the colony. Governor Bourke, under instructions from the English Parliament, made a new arrangement. There were to be no more free grants. In the settled districts all land was to be put up for auction; if less than five shillings an acre was offered, it was not to be sold; when the offers rose above that price, it was to be given to the highest bidder. This was regarded as a very fair arrangement; and, as a large sum of money was annually received from the sale of land, the Government was able to resume the practice, discontinued in 1818, of assisting poor people to emigrate from Europe to the colony.

9. The Squatters.—Beyond the surveyed districts the land was occupied by squatters, who settled down where they pleased, but had no legal right to their “runs,” as they were called. With regard to these lands new regulations were urgently required; for the squatters, who were liable to be turned off at a moment’s notice, felt themselves in a very precarious position. Besides, as their sheep increased rapidly, and the flocks of neighbouring squatters interfered with one another, violent feuds sprang up, and were carried on with much bitterness. To put an end to these evils Governor Bourke ordered the squatters to apply for the land they required. He promised to have boundaries marked out; but gave notice that he would, in future, charge a rent in proportion to the number of sheep the land could support. In return, he would secure to each squatter the peaceable occupation of his run until the time came when it should be required for sale. This regulation did much to secure the stability of squatting interests in New South Wales.

After ruling well and wisely for six years, Governor Bourke retired in the year 1837, amid the sincere regrets of the whole colony.

CHAPTER VII.

DISCOVERIES IN THE INTERIOR, 1817-1836.

1. Oxley.—After the passage over the Blue Mountains had been discovered—in 1813—and the beautiful pasture land round Bathurst had been opened up to the enterprise of the squatters, it was natural that the colonists should desire to know something of the nature and capabilities of the land which stretched away to the west. In 1817 they sent Mr. Oxley, the Surveyor-General, to explore the country towards the interior, directing him to follow the course of the Lachlan and discover the ultimate “fate,” as they called it, of its waters. Taking with him a small party, he set out from the settled districts on the Macquarie, and for many days walked along the banks of the Lachlan, through undulating districts of woodland and rich meadow. But, after a time, the explorers could perceive that they were gradually entering upon a region of totally different aspect; the ground was growing less and less hilly; the tall mountain trees were giving place to stunted shrubs; and the fresh green of the grassy slopes was disappearing. At length they emerged on a great plain, filled with dreary swamps, which stretched as far as the eye could reach, like one vast dismal sea of waving reeds. Into this forbidding region they penetrated, forcing their way through the tangled reeds and over weary miles of oozy mud, into which they sank almost to the knees at every step. Ere long they had to abandon this effort to follow the Lachlan throughout its course; they therefore retraced their steps, and, striking to the south, succeeded in going round the great swamp which had opposed their progress. Again they followed the course of the river for some distance, entering, as they journeyed, into regions of still greater desolation; but again they were forced to desist by a second swamp of the same kind. The Lachlan here seemed to lose itself in interminable marshes, and as no trace could be found of its further course, Oxley concluded that they had reached the end of the river. As he looked around on the dreary expanse, he pronounced the country to be “for ever uninhabitable”; and, on his return to Bathurst, he reported that, in this direction at least, there was no opening for enterprise. The Lachlan, he said, flows into an extensive region of swamps, which are perhaps only the margin of a great inland sea.

Oxley was afterwards sent to explore the course of the Macquarie River, but was as little successful in this as in his former effort. The river flowed into a wide marsh, some thirty or forty miles long, and he was forced to abandon his purpose; he started for the eastern coast, crossed the New England Range, and descended the long woodland slopes to the sea, discovering on his way the river Hastings.

2. Allan Cunningham.—Several important discoveries were effected by an enthusiastic botanist named Allan Cunningham, who, in his search for new plants, succeeded in opening up country which had been previously unknown. In 1825 he found a passage over the Liverpool Range, through a wild and picturesque gap, which he called the Pandora Pass; and on the other side of the mountains he discovered the fine pastoral lands of the Liverpool Plains and the Darling Downs, which are watered by three branches of the Upper Darling—the Peel, the Gwydir, and the Dumaresq. The squatters were quick to take advantage of these discoveries; and, after a year or two, this district was covered with great flocks of sheep. It was here that the Australian Agricultural Company formed their great stations already referred to.

3. Hume and Hovell.—The southern coasts of the district now called Victoria had been carefully explored by Flinders and other sailors, but the country which lay behind these coasts was quite unknown. In 1824 Governor Brisbane suggested a novel plan of exploration; he proposed to land a party of convicts at Wilson’s Promontory, with instructions to work their way through the interior to Sydney, where they would receive their freedom. The charge of the party was offered to Hamilton Hume, a young native of the colony, and a most expert and intrepid bushman. He was of an energetic and determined, though somewhat domineering disposition, and was anxious to distinguish himself in the work of exploration. He declined to undertake the expedition in the manner proposed by Governor Brisbane, but offered to conduct a party of convicts from Sydney to the southern coasts. A sea-captain named Hovell asked permission to accompany him. With these two as leaders, and six convict servants to make up the party, they set out from Lake George, carrying their provisions in two carts, drawn by teams of oxen. As soon as they met the Murrumbidgee their troubles commenced; the river was so broad and swift that it was difficult to see how they could carry their goods across. Hume covered the carts with tarpaulin, so as to make them serve as punts. Then he swam across the river, carrying the end of a rope between his teeth; and with this he pulled over the loaded punts. The men and oxen then swam across, and once more pushed forward. But the country through which they had now to pass was so rough and woody that they were obliged to abandon their carts and load the oxen with their provisions. They journeyed on, through hilly country, beneath the shades of deep and far-spreading forests; to their left they sometimes caught a glimpse of the snow-capped peaks of the Australian Alps, and at length they reached the banks of a clear and rapid stream, which they called the Hume, but which is now known as the Murray. Their carts being no longer available, they had to construct boats of wicker-work and cover them with tarpaulin. Having crossed the river, they entered the lightly timbered slopes to the north of Victoria, and holding their course south-west, they discovered first the river Ovens, and then a splendid stream which they called the Hovell, now known as the Goulburn. Their great object, however, was to reach the ocean, and every morning when they left their camping-place they were sustained by the hope of coming, before evening, in view of the open sea. But day after day passed, without any prospect of a termination to their journey. Hume and Hovell, seeing a high peak at some little distance, left the rest of the party to themselves for a few days, and with incredible labour ascended the mountain, in the expectation of beholding from its summit the great Southern Ocean in the distance. Nothing was to be seen, however, but the waving tops of gum trees rising ridge after ridge away to the south. Wearily they retraced their steps to the place where the others were encamped. They called this peak Mount Disappointment. Having altered the direction of their course a little, in a few days they were rejoiced by the sight of a great expanse of water. Passing through country which they declared to resemble, in its freshness and beauty, the well-kept park of an English nobleman, they reached a bay, which the natives called Geelong. Here a dispute took place between the leaders, Hovell asserting that the sheet of water before them was Western Port, Hume that it was Port Phillip. Hume expressed the utmost contempt for Hovell’s ignorance; Hovell retorted with sarcasms on Hume’s dogmatism and conceit; and the rest of the journey was embittered by so great an amount of ill-feeling that the two explorers were never again on friendly terms. Hume’s careful and sagacious observations of the route by which they had come enabled him to lead the party rapidly and safely back to Sydney, where the leaders were rewarded with grants of land and the convicts with tickets-of-leave.

Читать дальше