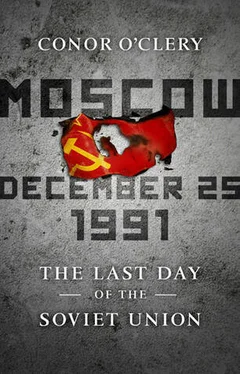

The demise of the superpower he inherited finally became inevitable the previous Saturday, when all the republics ganged up to reject even a weakened central authority. Only on Monday morning, just two days ago, did he decide—he had little choice—that he would announce his resignation this evening. It was only on Monday afternoon that he established the terms for a peaceful transition with his hated rival. This was a painful experience. And he is not even being accorded the dignity of a solemn farewell ceremony.

At least he does not face the prospect of exile or death, the fate of two other recently deposed communist leaders in Europe, Erich Honecker of East Germany and Nicolae Ceauşescu of Romania. But he knows there are people only too eager to discredit him to justify what they are doing.

Under the transition agreement the couple understand they have three days to leave the presidential dacha, their home for six years, after which they must give the keys to the new ruler of Russia. They will leave behind many memories of entertaining world leaders around the dining table and talking long into the night about reshaping the world. There is much to do now of a more mundane nature. They have to sort through books, pictures, and documents, and pack away clothes and private things to move to a new home. They have a similar task to perform at their city apartment on Moscow’s Lenin Hills, which also belongs to the state.

When Gorbachev moved his family here, they expected it would be for life. The dacha, called officially Barvikha-4, was the ultimate symbol of success for the top Soviet bureaucrat. They have occupied smaller government dachas during Gorbachev’s ascent to the pinnacle of Soviet power. As state-owned residences they were quite impersonal, and Raisa disliked that they were “always on the move, always lodgers.” But this was to be their final stop. This dacha was different. It was their creation. The yellow three-story complex was modeled in Second Empire style under Gorbachev’s personal supervision after he became general secretary of the Communist Party in 1985. In those days the party leader had emperor-like powers of command, and it was built in six months by a special corps of the Soviet army, earning the generals a few Medals of Labor. This had been Raisa’s first real home. “My home is not simply my castle,” she once said. “It is my world, my galaxy.”

Known by the security people as the wolfichantze (wolfs lair), the presidential dacha is serviced by a staff of several cooks, maids, drivers, and bodyguards, all of whom have their quarters on the lower floor or in outbuildings. It has several living rooms with enormous fireplaces, a vast dining room, a conference room, a clinic staffed with medical personnel, spacious bathrooms on each floor, a cinema, and a swimming pool. Everywhere there is marble paneling, parquet floors, woven Uzbek carpets, and crystal chandeliers. Outside large gardens and a helicopter landing area have been carved out of the 164 acres of woodland. The surrounding area is noted for its pristine air, wooded hills, and views over the wide, curving Moscow River.

For more than half a century Soviet leaders have occupied elegant homes along the western reaches of the river. This area has been the favored retreat of the Moscow elite since the seventeenth century, when Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich expressly forbade the construction of any production facilities. Stalin lived in a two-story mansion on a high bank in Kuntsevo, closer to the city. Known as Blizhnyaya Dacha (“nearby dacha”), it was hidden in a twelve-acre wood with a double-perimeter fence and at one time was protected by eight camouflaged 30-millimeter antiaircraft guns and a special unit of three hundred interior ministry troops. At Gorbachev’s dacha there is a military command post, facilities for the nuclear button and its operators, and a special garage containing an escape vehicle with a base as strong as a military tank.

Every previous Soviet leader but one left their dachas surrounded by wreaths of flowers. Stalin passed away in his country house while continuing to exercise his powers, and those who followed him—Leonid Brezhnev, Yury Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko—all expired while still in charge of the communist superpower. Only Stalin’s immediate successor, Nikita Khrushchev, a reformer like Gorbachev, had his political career brought to a sudden end when he was ousted from power in 1964 for, as Pravda put it, “decisions and actions divorced from reality.”

Today Gorbachev will suffer the same fate as Khrushchev. He will depart from the dacha as president of the Soviet Union. When he returns in the evening, he will be Gospodin (“Mister”) Gorbachev, a pensioner, age sixty—ten years younger than Khrushchev was when he was kicked out.

At around 9:30 a.m. Gorbachev takes his leave of Zakharka, as he fondly calls Raisa (he once saw a painting by the nineteenth-century artist Venetsianov of a woman of that name who bore a resemblance to Raisa). He goes down the wooden stairs, past the pictures hanging on the staircase walls, among them a multicolored owl drawn in childish hand, sent to Raisa as a memento by a young admirer. At the bottom of the stairs was, until recently, a little dollhouse with a toboggan next to it, a reminder of plans for New Year’s festivities with the grandchildren, eleven-year-old Kseniya and four-year-old Nastya; the family will now have to celebrate elsewhere. He spends a minute at the cloakroom on the right of the large hallway to change his slippers for outdoor shoes, then dons a fine rust-colored scarf, grey overcoat, and fur hat, and leaves through the double glass doors, carrying his resignation speech in a thin, soft leather document case.

Outside in the bright morning light his driver holds open the front passenger door of his official stretch limousine, a Zil-41047, one of a fleet built for party and state use only. Gorbachev climbs into the leather seat beside him. He always sits in the front.

Two colonels in plainclothes emerge from their temporary ground-floor lodgings with the little suitcase that accompanies the president everywhere. They climb into a black Volga sedan to follow the Zil into Moscow. It will be their last ride with this particular custodian of the chemodanchik, the case holding the communications equipment to launch a nuclear strike.

With a swish of tires, the bullet-proof limousine—in reality an armored vehicle finished off as a luxury sedan—moves around the curving drive and out through a gate in the high, green wooden fence, where a policeman gives a salute, and onto Rublyovo-Uspenskoye Highway. The heavy automobile proceeds for the first five miles under an arch of overhanging snow-clad fir trees with police cars in front and behind flashing their blue lights. It ponderously negotiates the frequent bends that were installed to prevent potential assassins from taking aim at Soviet officials on their way to and from the Kremlin. Recently some of the state mansions have been sold to foreigners by cash-strapped government departments, and many of the once-ubiquitous police posts have disappeared.

The convoy speeds up as it comes to Kutuzovsky Prospekt. It races for five miles along the center lane reserved for official cavalcades, zooms past enormous, solid Stalin-era apartment blocks, and hurtles underneath Moscow’s Triumphal Arch and across the Moscow River into the heart of the Russian capital. The elongated black car hardly slackens speed as it cruises along New Arbat, its pensive occupant unseen behind the darkened windows.

The seventh and last Soviet leader plans to explain on television this evening that he dismantled the totalitarian regime and brought them freedom, glasnost, political pluralism, democracy, and an end to the Cold War. For doing so, he is praised and admired throughout the world.

Читать дальше