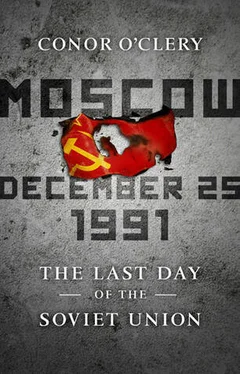

In reconstructing the events of this midwinter day, I have combined my interviews and my own research in television and newspaper archives with material from over a hundred memoirs, diaries, biographies, and other works that have appeared since the fall of the Soviet Union in English and Russian. I have also drawn on my experience observing Gorbachev and Yeltsin up close in the last four years of Soviet rule, when I was a correspondent based in Moscow. During this period I frequented the Kremlin and the Russian White House, where the fight between the two rivals played out. I hung around parliamentary and party meetings, grabbing every opportunity to question the two leaders when they appeared. I interviewed Politburo members, editors, economists, nationalists, Communist Party radicals and hard-liners, dissidents, striking coal miners, and countless people just trying to get by. I was a face in the crowd at pro-democracy rallies, at Red Square commemorations, and at the barricades in the Baltics. I traveled around Russia, from Chechnya to Yakutsk, and to the republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan, observing the changes sweeping the USSR that would lead to the denouement on Christmas Day 1991. And since then I have returned to Russia regularly, for both professional and personal reasons.

I was privileged to experience the last days of the Soviet Union and what came after not just as a foreign observer but as a member by marriage of a Russian-Armenian family. The Suvorovs live in Siberia, where they experienced the excitement, hardships, and absurdities of those turbulent years and taught me the joys of summer at the dacha. My philologist wife Zhanna was a deputy in a regional soviet, and later, when we moved to Washington, she worked for the International Finance Corporation on the post-1991 project to privatize Russia. My father-in-law, Stanislav Suvorov, a shoemaker now in his eighties and still working in a Krasnoyarsk theater, suffered under the old system. He served five years in jail for a simple act of speculation—selling his car at a profit. He later prospered by providing handmade shoes for top party officials. My mother-in-law, Marietta, a party member, welcomed the free market that came with the transition from Gorbachev to Yeltsin with the comment, “At least now I don’t have to humiliate myself to buy some cheese.” Nevertheless, I saw the pernicious effect on the family of economic and social chaos. My cousin-in-law Ararat, a police officer, was shot dead by the mafia in Krasnoyarsk. Marietta’s savings disappeared overnight with hyperinflation. My sister-in-law Larisa, director of a music school, went unpaid for months in the postcommunist economic chaos and one day received, in lieu of salary, a cardboard box of men’s socks. All this, and an attempt by the KGB to compromise me by trying (and failing) to intimidate Zhanna into working for them shortly before the fall of the Soviet Union, has given me a fairly unique insight into what was going on in the society that threw up Gorbachev and Yeltsin, and how it all came to a head.

In compiling the events of December 25, 1991, I have used only information that I have been able to source or verify. None of the dialogue or emotions of the characters has been invented. I have used my best judgment to determine when someone’s recollection is deliberately misleading and self-serving, or simply mistaken, as the mind plays tricks with the past and witnesses sometimes contradict each other. One person in the Kremlin recalls that it snowed heavily in Moscow on December 25, 1991, others that it didn’t (it was a dry, mild day, confirmed by meteorological records). Some players have vivid recall; others do not: Andrey Grachev and Yegor Gaidar were able to provide me with detailed accounts of what went on inside the Gorbachev and Yeltsin camps, respectively, but Yeltsin’s collaborator Gennady Burbulis told me he simply did not have memories of that long-ago day.

A note on names and spelling: Russian names contain a first name, a patronymic, and a surname, hence Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev. The respectful form of address is the first name plus patronymic, which can cause confusion outside Russia—once after I politely addressed Gorbachev on television as “Mikhail Sergeyevich,” a friend complimented me for being on first-name terms with the Soviet leader. Among family and friends a diminutive form of the first name is common, such as Sasha for Alexander, Borya for Boris, and Tolya for Anatoly. For the spelling of Russian names and words, I have used the more readable system of transliteration, using y rather than i, ii, or iy, thus Yury rather than Yuri. Different versions may appear in the bibliography, where I have not changed publishers’ spellings. For clarity I have included a list of the main characters (“Dramatis Personae”).

Many people made this book possible by generously sharing their time and insights. I would especially like to acknowledge Jonathan Anderson, Ed Bentley, Stanislav Budnitsky, Charles Caudill, Giulietto Chiesa, Ara Chilingarova, Fred Coleman, Nikolay Filippov, Olga Filippova, the late Yegor Gaidar, Ekaterina Genieva, Frida Ghitis, Martin Gilman, Svetlana Gorkhova, Andrey Grachev, Steve Hurst, Gabriella Ivacs, Tom Johnson, Eason Jordan, Rick Kaplan, Ted Koppel, Sergey Kuznetsov, Harold Mciver Leich, Liu Heung Shing, Ron Hill, Stuart H. Loory, Philip McDonagh, Lara Marlowe, Seamus Martin, Ellen Mickiewicz, Andrey Nikeryasov, Michael O’Clery, Eddie Ops, Tanya Paleeva, Robert Parnica, Claire Shipman, Olga Sinitsyna, Martin Sixsmith, Sarah Smyth, Yury Somov, Conor Sweeney, and the staff at the Gorbachev Foundation and the Russian State Library of Foreign Literature. A special thanks to Professor Stephen White of the University of Glasgow, who provided me with some out-of-print Russian memoirs; John Murray, lecturer in Russian at Trinity College Dublin, who read the manuscript and whose corrections saved me some embarrassment; and Clive Priddle of PublicAffairs, who inspired and helped shape the concept. No words are adequate to acknowledge the research and editing skills of my wife, Zhanna O’Clery, who traveled with me to Moscow a number of times to help track down archives and sources and whose involvement at every stage in the composition and editing of the book made it something of a joint enterprise.

During my tenure, I have been attacked by all those in Russian society who can scream and write…. The revolutionaries curse me because I have strongly and conscientiously favored the use of the most decisive measures…. As for the conservatives, they attack me because they have mistakenly blamed me for all the changes in our political system.

—Russian reformer Count Sergey Yulyevich Witte in his resignation letter as prime minister in 1906

During his six years and nine months as leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev is accompanied everywhere by two plainclothes colonels with expressionless faces and trim haircuts. They are so unobtrusive that they often go unnoticed by the president’s visitors and even by his aides. These silent military men sit in the anteroom as he works in his office. They ride in a Volga sedan behind his Zil limousine as he is driven to and from the Kremlin. They occupy two seats at the back of the aircraft when he travels out of Moscow, and they sleep overnight at his dacha or city apartment, wherever he happens to be. [1] 1 Palazchenko, My Years with Gorbachev and Sbevardreadze, 361.

The inscrutable colonels are the guardians of a chunky black Samsonite briefcase with a gold lock weighing 3.3 pounds that always has to be within reach of the president. This is the chemodanchik, or “little suitcase.” Everyone, even Gorbachev, refers to it as the “nuclear button.” Rather it is a portable device that connects the president to Strategic Rocket Forces at an underground command center on the outskirts of Moscow. It contains the communications necessary to permit the firing of the Soviet Union’s long-range nuclear weapons, many of them pointed at targets in the United States. The job of the colonels—three are assigned to guard the case, but one is always off duty—is to help the president, if ever the occasion should arise, to put the strategic forces on alert and authorize a strike.

Читать дальше